ANU Claims Hydrogen At $2-3 A KG By 2030 — I Say Not Bloody Likely

Hydrogen won’t be $2-3 per kilogram by 2030. It’ll be much cheaper!

Hydrogen is the car fuel of the future. Just not our future.

But I’m sure in some alternate future Jack Nicholson is President and Australians are labouring in underground hydrogen mines to fill the transport blimps of the California Federation.

The cars in our future will run off boring old electricity stored in batteries rather than the gas that makes up most of the sun.1 If you want to change my mind about this, just get out there and start producing hydrogen cars. You’ll only need to make about 2.1 million to match electric vehicles produced last year. Let me know after you’ve made one every 15 seconds for 12 months so I can blog about it.

Unfortunately, some politicians haven’t got the message that hydrogen driving isn’t taking off. They expect Australia to be exporting billions of dollars of hydrogen to Asian car owners in the near future. In reality, we’ll have better luck powering Asian cars if we lay a transmission line from here to Singapore.

This doesn’t mean Australia won’t ever export hydrogen. It’s used in many industrial processes and could be useful for aviation. After all, the only thing lighter than hydrogen is no hydrogen. But there’s no hope of exporting trillions of litres a day. We’re not going to end up the Saudi Arabia of hydrogen. We’ll have to be satisfied with just being the Saudi Arabia of camels.

For hydrogen exports to take off it will have to beat the competition on price and, given the falling cost of batteries and renewable energy, that looks impossible for road transport. But there is some good news for hydrogen. A working paper by Longden, Jotzo, Prasad, and Andrews of the Australian National University came out last month with the title:

It says by 2030 hydrogen produced from renewable energy in Australia may cost $2-3 a kilogram. While there’s nothing drastically wrong with the paper and they clearly explain how they arrived at their conclusions, I do not agree with them. I find the idea of hydrogen costing $2-3 in 10 years time borders on the absurd.

I think it will be much cheaper.

“I am from the year 2030. Come with me if you want to electrolyse.”

Why So Cheap?

For two main reasons.

- The future cost of renewable energy will likely be lower than their estimates.

- The average cost of electricity used for hydrogen production will be even less as the electrolysers will be shut down when electricity prices are high and ramped up when they’re low.

To be fair, the authors clearly think the cost of renewable energy could be considerably less than the figures they use. But when you work for a university you’re expected to base your conclusions on other people’s work. It is frowned upon if you instead wave your hands in the air and say, “I think it will be different!” But I don’t represent a university, so I’m free to wave my hands around like Kermit the Frog.

The Cost Of Solar Power Is Falling Fast

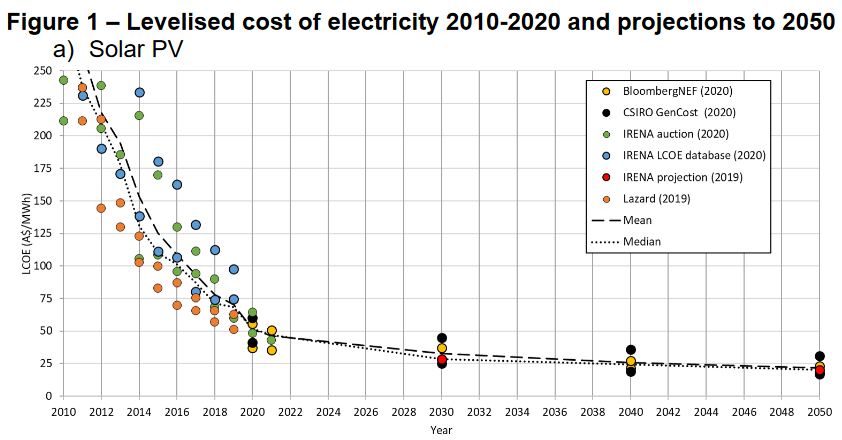

The paper uses CSIRO estimates for the levelized cost of energy from Australian solar farms built in 2020. These costs range from 4.1 to 6 cents per kilowatt-hour. That’s a lot cheaper than the cost of new coal power calculated using the same method. And for those who appreciate dark azure fields of blue, big solar has passed rooftop solar power on installed cost per watt.

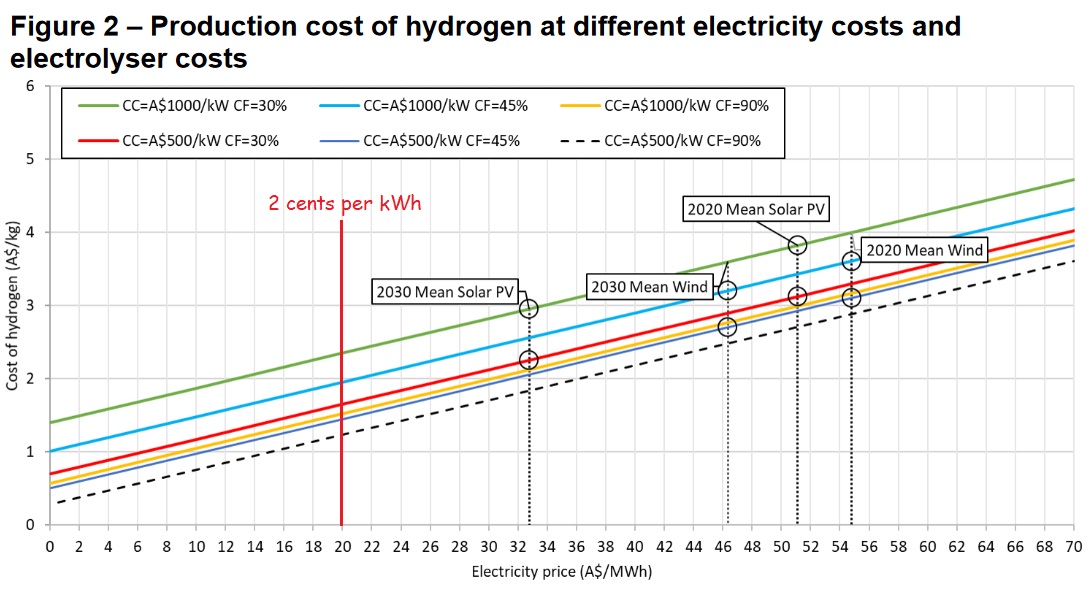

Estimates of the future cost of solar farm electricity are shown in the graph from the paper below. They also looked at wind power, but I’ll just show the figures for large scale solar energy, since they came in cheaper:

The Levelised Cost Of Energy (LCOE) figures on the left are given in dollars per megawatt-hour. $25 per megawatt-hour is equal to 2.5 cents per kilowatt-hour.

A major problem with these estimates is they assume an interest rate of 8.5%. This was fine decades ago, but is unrealistically high now. A figure of 3% would be much better and even that may be too much. No one will let me borrow money at that rate, but my friend can despite the fact he looks kind of shifty. Using the old rate keeps things consistent with their past results, but I think they should just bite the bullet…

“I EAT bullets for BREAKFAST.”

Shut up, Arnie.

…and use a more realistic interest rate. It will result in significantly lower estimates for renewable energy costs.

Real Life Solar Is Cheap

But there’s no need to rely on estimates of the future cost of big solar. We can look at current costs and see they’re pretty damn cheap. In the United Arab Emirates, they are building a giant solar farm for only around 1.9 Australian cents per kilowatt-hour produced over 30 years. That’s less than it costs to squeeze energy out of an Australian coal power station even if the coal is almost free.2

While 1.9 cents is the cheapest I know of, it’s not a one-off freak event that will never be repeated. These sorts of prices will soon be repeating on us like my girlfriend’s last attempt at a curry vindaloo. The cheapest solar energy in the US was offered at 2.7 Australian cents per kilowatt-hour but they threw in battery storage as well, so it now comes to around 5.4 Australian cents per kilowatt-hour.

While it may take Australia a few years to catch up to the rest of the world, we will get there. And by the time we arrive solar power will have fallen even further in price. While there are limits to how cheap it’s likely to get, I have no problem believing by the time 2030 rolls around, a hydrogen producer will be able to have a solar farm built for under 2 cents per kilowatt-hour generated.

Rooftop Solar Power Also Helps

While big solar is coming down in price, that doesn’t mean rooftop solar stops making sense. Its output will continue to expand, placing downward pressure on electricity prices during the day. Rooftop solar power has an advantage over solar farms because it still makes sense to install no matter how low the wholesale price of electricity gets — even it it’s zero .

Thanks to big solar, small solar and wind power we can be confident that future daytime electricity prices will be very low.

Production Will Work Around High Electricity Prices

Estimates for energy costs in the paper are for the average amount of money a solar or wind farm needs to be paid per kilowatt-hour to be built. But hydrogen producers won’t actually pay these prices because they will shut down when electricity is expensive and ramp up when it’s cheap. A hydrogen production facility could build a solar farm and use most of the generation to make hydrogen, but sell to the grid when its price is high. This could be late in the afternoon, soon after sunrise in winter, on cloudy days, or any other time they can make more money from selling electricity than using it to make hydrogen. So the average cost of electricity used by hydrogen producers will lower than the average cost of electricity.

Large industrial users of energy, such as BHP or GLNG, pay the wholesale spot price for grid electricity, which is a lot less than we pay on household bills. Large hydrogen producers will be able to get a similar deal and take advantage of periods of low grid electricity prices.

Hydrogen Can Offset Emissions From Grid Energy

The drawback of using grid electricity is some may come from fossil fuels, so the hydrogen produced won’t be entirely green. But this is easily fixed. It’s not difficult to work out the carbon intensity of grid electricity at the time it’s used, so all that needs to be done is to purchase carbon credits — real ones, not fake ones — to offset the emissions to keep the hydrogen green. All they need to do is get on the phone — or since it will be the future it’s more likely to be this internet thing all the cool kids are talking about — and say:

“Hey, Vinnie! Ya got some carbon credits for me?”

“Yeah, sure. How many ya need?”

“About a thousand tonnes.”

“I can do that for ya. It’ll cost ya 70 K.”

“Ya breaking my balls, Vinnie. Ya breaking my balls here. You can give me a better deal than that.”

“Actually, carbon credits are a commodity and their price is set by a transparent market mechanism, backed up by audits and random inspections of carbon capture projects. So there is no room to move on their price and to keep our fees low we have a fixed, non-negotiable transaction charge.”

“I see your point and I appreciate you explaining it to me. You’re repairing my balls, Vinnie. You’ve repaired my balls.”

Because hydrogen producers can and will time their grid electricity use for when it is mostly renewable — or even all renewable — the total amount of carbon credits they will need to buy won’t be high.

Six Different Scenarios

The paper gives the cost of hydrogen production under six scenarios that depend upon:

- The capacity factor the hydrogen electrolysers are used at, and…

- The cost of the electrolysers.

Capacity Factors

The capacity factor is the percentage of time the electrolysers that produce hydrogen are run for. The paper considered three different amounts. These were chosen for stupid reasons, as they are based on capacity factor figures for solar farms, wind farms, and running an electrolyser off the grid but regularly shutting it down for maintenance:

- 30% capacity factor based on solar power.

- 45% capacity factor based on wind power.

- 90% capacity factor based on grid power.

In reality, businesses don’t work that way and the electrolyser capacity factor will be based on whatever makes them the most money.3 The capacity factor of wind and solar farms would only be an issue for off-grid hydrogen production and that’s not likely to occur on any large scale.4

While the reasons they used the two lower capacity figures don’t make a lot of sense, they are still useful. The 30% and 45% capacity factors can represent hydrogen producers that only use the lowest cost electricity available.

Hydrogen Electrolyser Costs

The paper uses two different costs for hydrogen electrolysers:

- $1,000 per kilowatt of capacity

- $500 per kilowatt of capacity

I don’t know enough to have any real opinion about the future cost of electroysers, so I am willing to run with their figures. While the world is not going to produce the vast amounts of hydrogen that would be required for road transport, so much money is going into hydrogen research I have no trouble believing they could get down to $500 a kilowatt.

The Hydrogen Cost Graph

The cost of hydrogen per kilogram with the three different capacity factors and two different electrolyser costs are shown in a graph below. However, because I believe that in 2030 the cost of electricity used by large hydrogen producers will average around 2 cents per kilowatt-hour or less, I have put a red line through the graph at that point:

The paper tentatively says hydrogen prices could approach $2 a kilogram by 2030. If they instead pay an average of around 2 cents per kilowatt-hour for the electricity they use, then the cost of hydrogen per kilogram with an electrolyser capacity factor of 45% would be:

- $1,000 per kilowatt electrolyser cost — $2 per kilogram

- $500 per kilowatt electrolyser cost — $1.40 per kilogram

Since I suspect electrolysers will fall in price and/or have higher efficiency than the 69% assumed in the paper,5 I think the lower price is more likely.

My Hydrogen Price Prediction

I also think it’s possible by 2030 that the electricity used by hydrogen producers — which is different from the average wholesale spot price — will average significantly under 2 cents per kilowatt-hour, further reducing the cost of hydrogen. However, there is a lot of uncertainty because prediction is difficult, especially when it comes to the future, so I am going to add a lot of wriggle room into my prediction, which is:

For large industrial hydrogen production that gets underway around 2030, the maximum production cost of hydrogen will be around $2 per kilogram in today’s money. The actual production cost is likely to be under $1.50 and — if we’re lucky — it will be around $1 per kilogram.

Cheaper Than Hydrogen From Coal

The paper says the CSIRO cost estimate for hydrogen produced from coal in the future is at least $2.27 a kilogram, so no one should want to do that if my prediction is right. But note the CSIRO figure is pretty low considering a trial coal-to-hydrogen plant in Victoria is producing it for $165,000 per kilogram.

Is $1-2 A Kilogram Hydrogen Cheap Enough?

My prediction for the cost of hydrogen is low, but it won’t matter if there are even cheaper alternatives available.

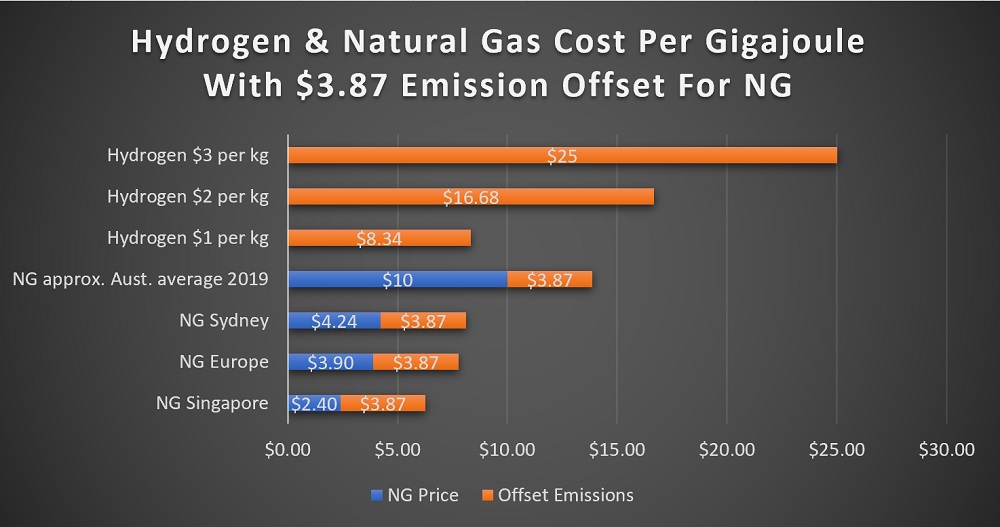

If hydrogen is $2 per kilogram then since it contains 120 megajoules of energy,6 the cost per gigajoule is $16.68. If the cost of hydrogen is $1 per kilogram then it comes to $8.34 per gigajoule.

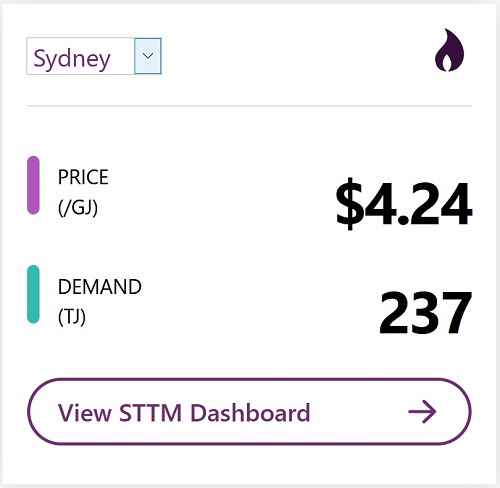

The reason why I am giving the cost per gigajoule is that it’s how natural gas is sold. At the moment it’s $4.24 per gigajoule in Sydney:

That’s almost half the cost of hydrogen at $1 per kilogram.

Despite the fact Australia is a major natural gas exporter, current prices overseas are even lower than this:

If you are wondering why we have higher prices here in Australia, there is a good reason why large companies charge us more for gas. It’s because they can.7

High Gas Prices May Never Return

As the world economy recovers from our inability to keep cooties to ourselves, we can expect the price of natural gas to rise. But I think its average price is likely to remain under $10 per gigajoule and we are unlikely to return to the days of high world gas prices we saw earlier this century for two main reasons:

- There is now far more international gas export capacity than in the past, increasing supply and competition.

- The falling cost of renewable energy — especially solar energy — is reducing the demand for natural gas. Not just for electricity generation, but also heating and industry.

By the time 2030 rolls around I suspect natural gas will be cheap compared to the average over the past 10 years, so hydrogen may have a hard time competing with it.8

Natural Gas Emissions Can Be Offset

A major drawback of burning natural gas is it creates CO2 and we have too much of that in the atmosphere already. Also, natural gas is mostly methane, which is a greenhouse gas around 34 times more powerful than CO2 when measured over a century. If just 1% of natural gas leaks into the atmosphere before it’s burned it is a serious problem.

A gigajoule of natural gas weighs 18 kilograms. When burned it combines with oxygen to create 50 kilograms of CO2. It’s possible to remove this CO2 from the atmosphere and sequester it long term to make natural gas as green as renewably produced hydrogen. So for hydrogen to be competitive it would have to be cheaper than the cost of natural gas plus the cost of offsetting its emissions by capturing and sequestering the CO2 released — plus extra to make up for methane leaks.

The Cost Of Emission-Offset Natural Gas

I think a reasonable estimate of what it may cost to remove CO2 from the atmosphere long-term on a large scale is around $70 a tonne.9 That’s 7 cents a kilogram, so removing the CO2 produced by burning one gigajoule of CO2 will cost $3.43. If 1% of natural gas leaks into the atmosphere10 then compensating for that raises the cost to $3.87.

If we add the cost of offsetting greenhouse gas emissions to the current cost of natural gas in Sydney it comes to $8.11 per gigajoule which is less than a gigajoule of hydrogen that costs only $1 per kilogram to produce.

If the cost of producing hydrogen is $2 a kilogram then the price of natural gas can be $12.80 a gigajoule and it will still be cheaper to use it instead and offset its emissions. I think there’s an excellent chance the price of natural gas will never have an annual average that high ever again.

Alternatively, if you think my estimate of the cost of offsetting CO2 emissions and methane leakage is way too optimistic and believe it will be twice as high, then natural gas at $8.93 a gigajoule will still be cheaper than hydrogen that costs $2 per kilogram to produce.

Hydrogen Has Some Challenges

To be competitive with emission offset natural gas, hydrogen not only has to be cheaper per gigajoule it also has to be cheaper after other disadvantages are factored in. These include:

- Hydrogen is more difficult and costly to liquefy for transport — on the other hand, once that’s done it’s much lighter.

- Due to hydrogen embrittlement and corrosion, most existing natural gas infrastructure can’t use hydrogen and only a modest amount can be added to natural gas before it starts causing problems.

- Some safety issues, including hydrogen burning with a mostly colourless flame that can make it hard to see.11

- If used to reduce iron in steelmaking, one gigajoule of hydrogen will remove 67 kilograms of oxygen from iron ore while one gigajoule of natural gas will remove 72 kilograms of oxygen, giving natural gas a modest advantage.

- Hydrogen that leaks into the atmosphere reduces the breakdown rate of methane and so acts as a mild greenhouse gas. Because hydrogen is the leakiest of all gases this can’t realistically be stopped and can only be minimized.

Given how cheap electricity is likely to be, I expect homes and businesses will give up using burnable gas altogether, rather than line up to buy hydrogen stoves and Hindenberg hot water systems. When it comes to electricity generation, rather than buy hydrogen tolerant turbines or use hydrogen fuel cells, it should usually make more economic sense to use low-cost batteries combined with cheap renewables.

We Should Export Emission-Offset Natural Gas

Even though I think hydrogen may be produced at a much lower cost than the sensible people who wrote the paper suggest, it still may not compete with the cost of natural gas plus offsetting its greenhouse gas emissions. If hydrogen may have trouble competing even if it comes in at my optimistic estimate, then why the hell is our government funding hydrogen research when could start exporting emission offset natural gas right now?

The answer to that is, the government would rather sink vast amounts of money into researching a possible solution than admit that our third largest export kills people. Since our second-largest export — coal — also kills people, I think we should really be cutting back on the amount of killing the stuff we sell causes. We put warnings on cigarette packets and charge taxes to cover its health costs, so I don’t see why fossil fuels should be any different.

Australia Can Be A Low-Cost Producer Of “Green” Natural Gas

At the moment there appear to be 5 main things that give a country an advantage when it comes to capturing and sequestering carbon emissions. These are:

- Stable and trustworthy government.

- A large agricultural sector.

- Transportation networks such as roads, railways, ports, and navigable rivers — we have the first three.

- Land

- Ocean

I know it’s hard to believe, but Australia actually has number 1. While the place seems like a nuthouse from the inside, when you look at the rest of the world we’re actually doing quite well. In the southern hemisphere the competition basically comes down to New Zealand and we have more of the other numbers.

There are methods of capturing and sequestering carbon Australia can start immediately and we can also use renewable energy certificates (LGCs) currently created as part of our Renewable Energy Target scheme to offset emissions.12 Australia could easily become the Saudi Arabia of — no, that’s not right — Australia could easily become the Australia of emission offset natural gas.

We have been stupid to spend so much money researching hydrogen which only has the potential to be low carbon energy export in the future, when we could be exporting emission offset natural gas right now. Instead of paying money to research hydrogen production, we should be encouraging other countries to pay us for carbon-neutral natural gas.

If selling 100% emission offset natural gas is difficult at first, we can start off easy:

“Hey, Japan! You want 10% of your natural gas imports to be carbon neutral, don’t you?”

“Yo! South Korea! You’re not going to let the Japanese beat you, are you? You’ll go for 15% emission offset natural gas, right?”

That’s how you do business. Exploit lingering hostility and racism.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t produce and export hydrogen if it looks like a moneymaker, but we can let other countries spend the money developing it. It’s not as if getting a head start is going to help us. It will be produced where large companies believe it will make them the most money.

Emission-offset natural gas is cheaper than hydrogen right now and, if predictions by people who aren’t crazy are correct, it may be cheaper for decades to come. The infrastructure required for its transport and use already exists, so there’s no chicken and egg problem as with hydrogen. We should take advantage of the opportunity that emission-offset natural gas exports offer and shouldn’t waste time and money on something that may be a pipe dream. Specifically, a fluorinated ethylene propylene pipe to prevent hydrogen embrittlement.

Footnotes

- Since we’ll use a lot of solar energy to charge those batteries, in a roundabout way, hydrogen will be supplying it. Of course, in an even more roundabout way, that’s also true for petrol and diesel.

- Many Australian power stations use stranded coal which is, effectively, almost free. Coal is stranded if it has no other economical use. This applies to Victoria’s brown coal, Western Australia’s kind of blackish coal, and — due to falling world demand — a number of black coal mines without rail access to coal terminals.

- I find that academics often lack an understanding of both business and international energy trading markets. However, by peeling potatoes in my parent’s catering business, I was magically granted the knowledge I claim they lack by the free enterprise fairy.

- There are people talking about producing hydrogen off any major Australian grid in the Northern Territory, but the intention there is to use a loooooooong cable to connect to the Indonesian, Singaporean, and Malaysian grids.

- Right now electrolysers can have an efficiency well above 69%, but hydrogen producers won’t necessarily use the highest efficiency electrolysers. They’ll use whatever provides the lowest cost overall. If the cost of electricity they use is very low then — depending on what happens with electrolyser technology — they should have an incentive to use cheaper, less efficient, electrolysers.

- This is the Lower Heating Value or LHV of hydrogen. The Higher Heating Value or HHV is 142 megajoules per kilogram, but LHV is the more relevant and appropriate figure to use.

- There are good reasons and bad reasons why natural gas costs so much in Australia and it would take me a lot of time to untangle them. My advice is — screw natural gas. Get a large solar power system, go all-electric, and disconnect from the gas line so you’ll no longer have to pay them money again and you’ll reduce the amount of methane leaking to the atmosphere from domestic gas lines.

- Yes, this does mean politicians who claim we can have a gas led recovery are idiots. Alternatively, if they knowingly want to spend tax payer’s money on something that kills taxpayers, they are evil.

- Potential low-cost methods of CO2 capture and sequestration involve turning plant matter into charcoal and burying it, dumping plant matter at the edge of the continental shelf so it is covered in sediment, and mucking around with various types of rocks.

- A leakage rate of 1% or less may seem optimistically low, but I if gas companies were charged for their leaks, as I am suggesting, I think the amount would suddenly magically decrease.

- But there are some safety advantages as well. Because hydrogen is so light it will collect near the ceiling and the distribution of humans is statistically greater close to the floor. Of course, if enough hydrogen builds up, this can happen but methane can have much the same effect.

- Since renewable energy mostly displaces coal generation, Large-scale Generation Certificates (LGCs) at their current price of $48 should currently reduce emissions at a lower cost than my $70 per tonne of CO2 figure.

Original Source: https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/anu-cheap-hydrogen/