Renewables Need More Long Distance Transmission. Low Interest Rates Can Make That Happen.

Long-distance transmission sends electrical energy from where it’s generated to where it’s used. If we had more of it, electricity prices would be lower, and the integration of solar and wind farms would be easier. Thanks to record low-interest rates, more of it is exactly what we’re going to get.

Not only will transmission capacity be increased between the five, already gridded together, eastern states — we may even get an undersea transmission cable linking the Northern Territory to Indonesia and Singapore. Most bizarre of all, the eastern states may be connected to the far distant land of Western Australia where they drink swan flavoured beer, and the sun hangs around in the sky for an average of two hours and 20 minutes after it has set in Sydney.

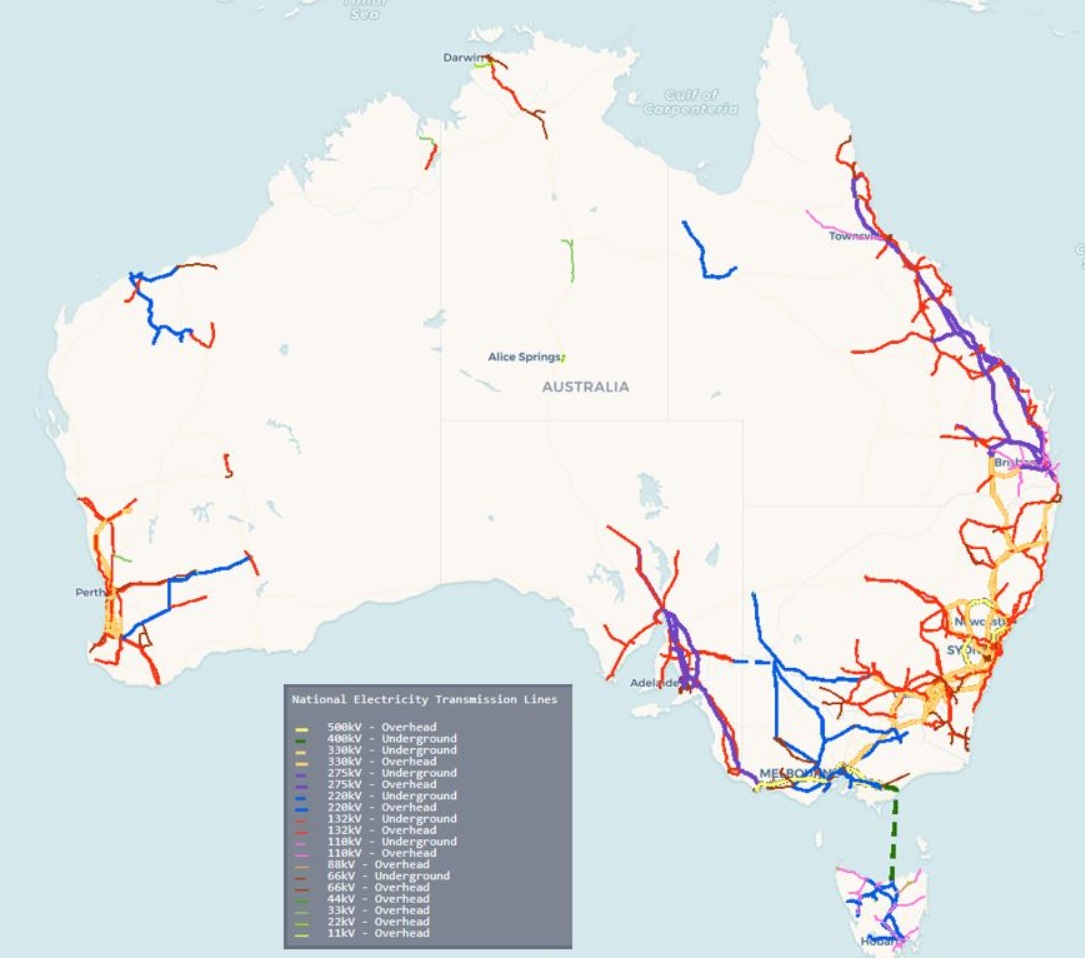

Existing Electricity Transmission

Large generators — whether solar farms, wind farms or pollution-spewing coal power stations — all have a location problem. Unlike rooftop solar, they’re not located where their power is used. The solution used is long aluminium cables to send the electricity where it’s required.

The 5 eastern states are already interconnected to varying degrees. This happened on the Pacific side due to the higher population density that has resulted from these states being habitable.

I’m not saying the Northern Territory and Western Australia aren’t habitable by humans, but I will say they’re not habitable by the Dutch. Not the sane ones, at least. Not unless there’s air conditioning.

Because the populated parts of the NT and WA are surrounded by inhospitable oceans of desert and/or channel country, they have their own separate grids; one main one and two or three itty bitty ones. It’s a very different situation from the Eastern States where sunshine falling on an Adelaide roof can contribute to keeping Townsville refrigerators running.

Here’s a map with a key that’s almost impossible to read, showing Australia’s existing high voltage transmission lines:

Interstate Electricity Transmission Is Relatively New

Australia’s first interstate transmission1 came about as part of the Snowy River Scheme that linked New South Wales and Victoria. But this providing clear evidence states could swap electricity without catching cooties, it was well over a decade before any other state tried it. Despite the electric connection they could easily have had, states were very reluctant to hook up. I know this sounds odd in these internet-connected days. Still, you have to remember, this is a country that decided every state should be free to express its individuality by picking whichever railway gauge best suited its mood and we ended up with 3 of them.2

Australia has traditionally had much less long-distance transmission than would have made sense in retrospect. This is despite the fact there was massive over-investment in grid infrastructure early last decade. This mis-investment was less about long-distance electricity transmission and more about beefing up grids to cope with an expected increase in electricity demand that never occurred. Instead, grid consumption slowly declined. Electricity prices shot up to pay for the extra infrastructure, which caused people to use even less electricity. It was pretty stupid.

I think we have learned maybe 3% of what we should have from that experience, so here’s hoping things go better with the new build-out of long-distance transmission.

Popularisation Of Transmission

Electricity transmission between states didn’t take off until a group of publicly minded naughty schoolboys formed a band to popularize the idea through music. Their songs included:

Admittedly, they didn’t have any real success until their producer made them change the lyrics, but at least they stopped him from changing the name of their band — AC/DC.

Two Types Of Transmission: AC & DC

There are two types of long-distance electricity transmission:

- High Voltage Alternating Current (HVAC)

- High Voltage Direct Current (HVDC)

High Voltage Alternating Current (HVAC): The most commonly used electricity transmission method uses alternating current (AC). This involves electrons in a cable all rushing one way and then altering their direction and rush back the way they came. This happens 50 times a second in Australia and most other countries, but in a few places, it’s 60 times because variety is the spice of electrical equipment incompatibility.

HVAC has commonly been used ever since Thomas Edison lost the “war of the currents“. A failure that resulted in him dying with nothing but the love of his family and over $200 million in today’s money. Nikola Tesla, the genius who won the battle, had to make do with a nice hotel room and the love of a pigeon.

High Voltage Direct Current (HVDC): While Thomas Edison was on the wrong track when he backed DC current for homes and businesses, developments in High Voltage Direct Current really have nothing to do with what he was on about and doesn’t vindicate his DC desire in any way what-so-ever.

Direct Current (DC) travels in one direction in a loop. By using high voltages, it can allow long-distance transmission with minimal losses. This means it will be used for any extremely long-distance new transmission lines, such as Australia to Singapore or Australia to Australia if we ever connect WA to the Eastern States.

HVAC versus HVDC: With HVAC transmission the current is synchronized with the grid. This means the electrons all rush back and forth in the same direction at the same time. Because of this, adding additional HVAC transmission to a grid can strengthen it and prevent blackouts by helping keep distant grid regions synchronized. Unfortunately, if something goes wrong at one end of the electricity transmission line, it can potentially cause a blackout at the far end.

HVDC is unsynchronized. This means it only supplies energy and doesn’t directly contribute to the system strength of the grid. It also means problems can’t propagate. This is handy if we build an interconnector to Indonesia and Singapore, as we’d just piss each other off if problems could leap across the Java and Timor seas.

How Extra Transmission Lowers Electricity Prices

Long-distance electricity transmission reduces the cost of electricity in four main ways:

- Improved market efficiency

- Increased competition

- Shared ancillary services

- Integration of renewable generation

- Geographic dispersion and time-shifting.

Market Efficiency: If electricity is cheap in South Australia and expensive in NSW, consumers in the states can only benefit if there is available transmission capacity. More electricity transmission allows more low-cost energy to be sent where it’s needed most, reducing bottlenecks and lowering prices.

Competition: We’re supposed to be protected from price gouging by competition. But there aren’t enough electricity providers to prevent a large supplier using their market power to drive prices higher than they would otherwise be. More transmission allows more suppliers to contribute, increasing competition.

Ancillary Services: These support the electricity grid in a range of ways to keep it stable and prevent blackouts. Improved transmission can allow different regions to share some of these ancillary services and reduce their total cost.

Integrating Renewables: Wind and solar farms are relatively inexpensive to build these days — provided there’s existing transmission capacity available for them to use. More transmission allows more large scale renewable energy be integrated into the grid and supply most of the energy they generate, instead of being forced to curtail output when electricity transmission capacity is congested.

More renewable capacity helps keep electricity prices low, as wind and solar power have no fuel cost. While constructing solar and wind farms costs money, once they’re completed their operating costs are minimal compared to gas and coal power.

Geographic Dispersal: Imagine flat. Double it. That’s most of Australia. Being the least lumpy continent3 results in a lot of correlation between wind speeds in South Australia, New South Wales, Victoria, and Tasmania. But in northern Queensland, the wind does its own thing and can be blowing hard while there’s hardly a breeze in the rest of the country. It’s similar with solar; Some regions can be overcast while others have blazing sunshine. This geographical dispersion of variable renewable capacity allows for a more constant and reliable supply of energy from wind and solar power and is dependent on adequate electricity transmission capacity.

Time Shifting: This usually refers to peak demand occurring at different times, which allows additional transmission to reduce the cost of meeting demand during peaks. But I’m also going to use it to refer to the fact the sun rises and sets at different times depending on where you are in the country. While it varies according to the season, on average, the sun in Perth sets around 2 hours and 20 minutes after it sets in Sydney. This means an electricity transmission line to WA could send solar power east for hours after the sunset in the nation’s largest city.

Low-Interest Rates = Much Cheaper Transmission

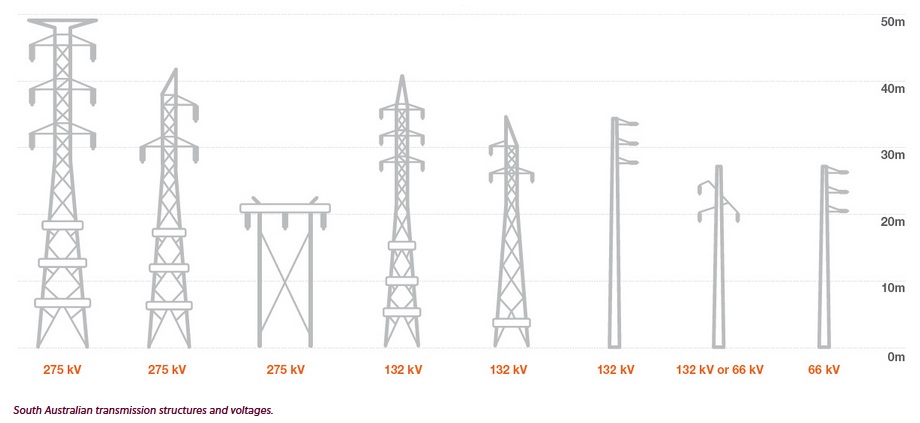

Long-distance transmission isn’t cheap to build, but it’s cheap to maintain and can be used for a very long time because it has no moving parts. One claim says it can last 40+ years underground and 80+ years when strung overhead from transmission towers.

Transmission towers. (Image Source: Electranet, who got it from South Australian transmission structures and voltages.)

This means the main costs of long-distance transmission are:

- The cost of actually building it.

- The cost of capital. Either the cost of interest payments on money borrowed or — if you just happen to have a couple of billion dollars lying around — what you could have made from an alternative investment.

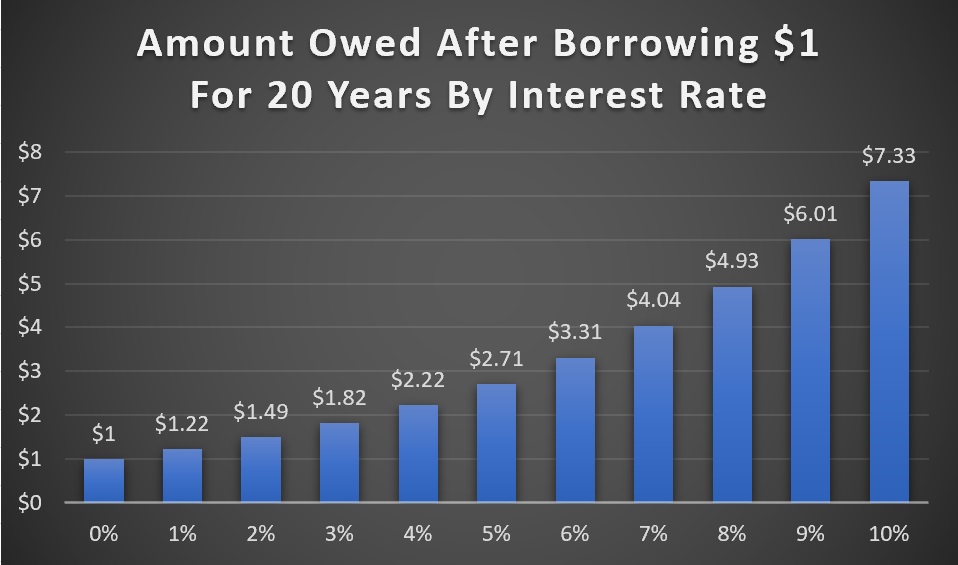

Less than a decade ago, the cost of capital was the largest part. But now, with interest rates at around zero, this cost has mostly disappeared. You may complain that no one’s letting you pay zero percent interest on your home loan as in Denmark, but if you are breaking ground on a giant, government-backed, billion-dollar infrastructure project in Australia, the interest you’ll have to pay is next to nothing at the moment. This has massively decreased the cost of building electricity transmission capacity, as the graph below suggests:

I used a period of 20 years in the graph above simply because it’s a length of time people can wrap their heads around. It’s not how transmission projects are paid for. They don’t just borrow money for 20 years and pay it back as a lump sum. It’s a little more complicated than that. But the graph does show how falling interest rates can massively reduce the cost of a project.

When it comes to building the infrastructure we need to shift away from fossil fuels, whether it’s long-distance electricity transmission, solar and wind farms, energy storage, or factories that spit out electric cars — the cost of building these things has never been cheaper.

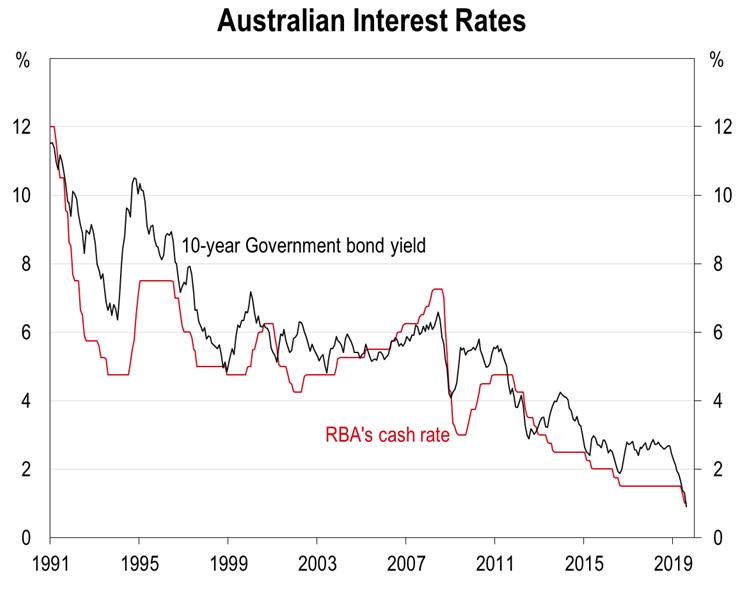

Return Of High-Interest Rates Unlikely

Interest rates have been trending down for 30 years and are unlikely to return to high levels any time soon. There may be a temporary increase after COVID-19 is defeated, but I’m sure low rates will be around long term.

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has a cash rate that is now 0.1%. This is the rate at which they’ll lend money to large, trusted, financial institutions. The government bond rate has actually gone slightly negative. (Image Source: ABC News.)

Electricity Transmission Projects

A lot of new transmission capacity is going to be built within states. One example is the Eyre Peninsula electricity line upgrade in South Australia, which will use transmission towers stronger than those that got bent to the ground in a storm 5 years ago.

Some politicians blamed the blackout that resulted from this on renewable energy. Personally, I’m more inclined to blame powerful winds than wind power… (Image Source: ABC News and they credit Tom Fedorowytsch.)

Rather than give details of smaller projects that only cost hundreds of millions of dollars, I’ll just mention the inter-state and international ones that cost billions. Below, are a list of projects at various points of their planning process. I’ve put them in rough order of how likely they are to go ahead:

- Victoria to NSW Interconnector West (VNI West)

- Project Energy Connect Between South Australia and NSW

- Project Marinus Interconnector between Tasmania and Victoria

- The Australian-ASEAN Power Link (AAPL) by Sun Cable from the Northern Territory to Indonesia and Singapore

- Western Australia To South Australia

Victoria To NSW Interconnector West

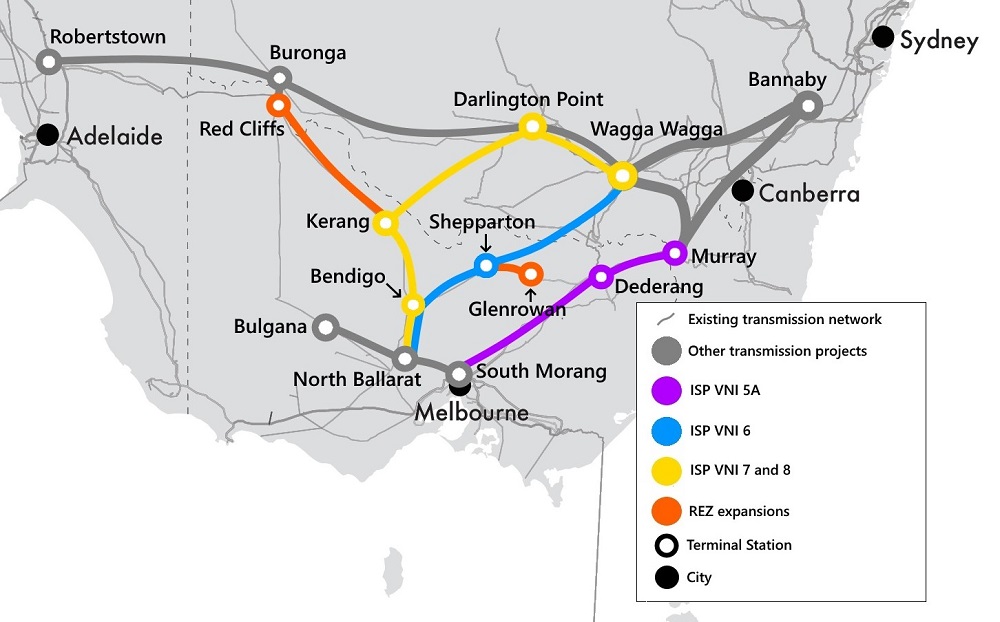

The Victoria to NSW Interconnector West, or VNI West to its friends, is expected to provide an additional 1.8 gigawatts or so of transmission capacity between the two states. While the exact plan isn’t finalized, the estimated cost will range from $1.3 to $1.9 billion, and it may be finished by 2027.

Proposed new VNI West transmission corridors. One of these coloured lines is expected to become an actual transmission line. (Image Source: AEMO)

Note that a smaller, 170-megawatt interconnector also planned between the two states is simply called VNI, so it’s easy to confuse the two.

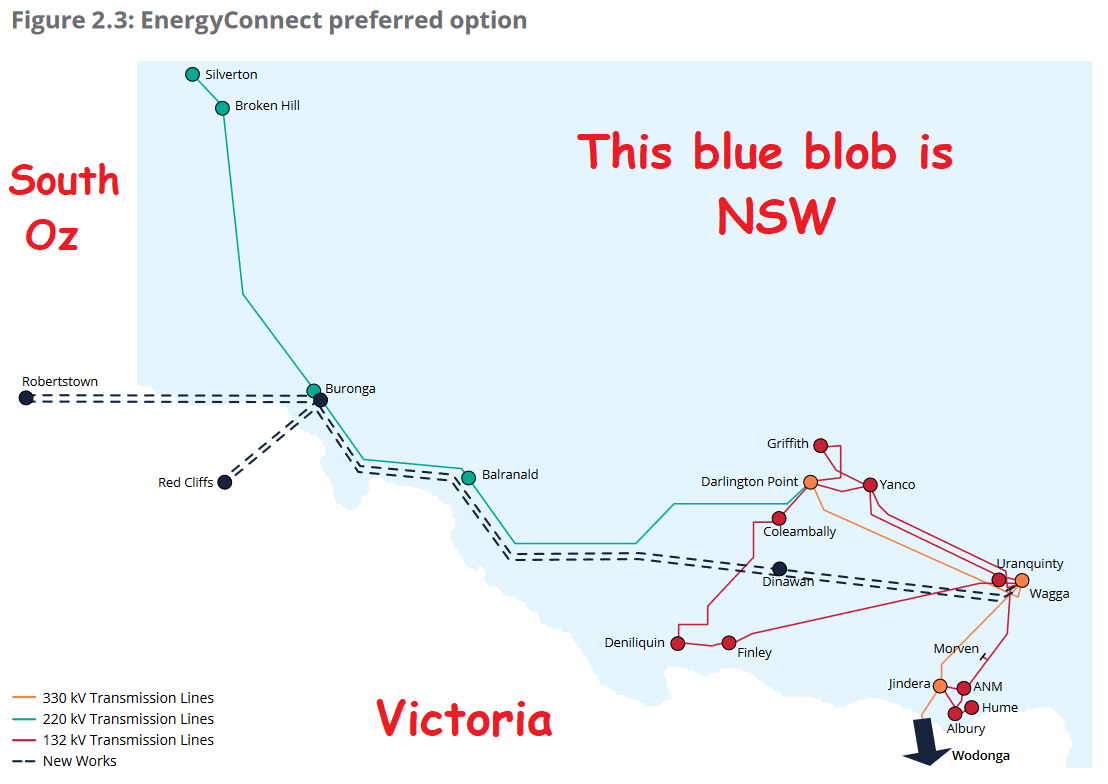

Project Energy Connect Between SA & NSW

Project Energy Connect is a plan to build an 875 km transmission line with a capacity of around 800 megawatts between South Australia and NSW. While SA has two interconnectors with Victoria, this will be the first with NSW. It’s expected to be completed in 2023, which is quick for a large project like this.

Projections are it will lower average annual household electricity bills by around $100 in South Australia and $61 in NSW. Because there are four and a half times as many people in NSW, that state will receive the greatest total benefit. At the moment it’s not clear how many years households will have to wait before they actually see a benefit on their electricity bills. The year 2030 is one date that was thrown around recently. (Funny how this delay wasn’t mentioned around election time in SA.)

The map above was clearly made by someone with a personal connection to Wagga Wagga. I can tell this because they called it Wagga, which is a social faux pas4 unless you or your relatives live there.

The cost estimate has risen to $2.4 billion, but it still looks almost certain to go ahead — despite recent arguments over funding.

Project Marinus Interconnector Between Tasmania & Victoria

Tasmania’s only interconnector with the mainland is Basslink. The folly of having only one was revealed in 2015 when it failed during a drought that lowered hydroelectric output in the Apple Isle. The electricity supply shortfall was so bad it contributed to blackouts in the Philippines.

I know that sounds odd because there’s no Manila interconnector yet. It occurred because diesel generators were shipped from there to Tasmania because Tasmanians were willing to pay more to not sit in the dark.5

The proposed Project Marinus will consist of a 750-megawatt connection by 2028 and a second 750-megawatt interconnector by 2032. This will give Tasmania 4 times its current interstate transmission capability, and 3 separate cables mean that if one fails it won’t be a serious problem.

All the interconnectors will be HVDC, allowing Tasmania to remain out of synch with the rest of the nation. This is probably for the best, since I hear they’re so out of synch Tasmanians will soon start partying like it’s 1999.

Sun Cable — Australian-ASEAN Power Link (AAPL)

This proposed project, which may go ahead, consists of a 3,750 km underwater HVDC transmission line from the Northern Territory to Indonesia and Singapore. The plan includes a 13.1 gigawatt solar farm in the NT with 33 gigawatt-hours of battery storage. This is an ambitious project, but given the Northern Territory has better solar resources than Indonesia and Singapore, as well as enough room to build giant solar farms, then — thanks to low-interest rates — it may proceed.

WA & SA Interconnector

You may think the idea of sending an extension cord across the ocean to Asia seems far fetched. Still, I think the idea of an electricity interconnector between Western and Eastern Australia is even nuttier.

The international interconnector will have hundreds of millions of potential customers, while there are only 2.7 million West Australians. Also, instead of connecting an area of great solar resources to a not-so-great area, this will be connecting great to great.

But despite the problems, some people claim it will easily pay for itself. Provided they can convince enough other people they’re not nuttier than a lumpy chocolate bar; then we will eventually electrically connect all Australian states. Just don’t be surprised if it doesn’t happen until after we’ve plugged Japan into the end of a giant extension cord.

Alternatives To Transmission

So far I’ve written as though more long-distance transmission capacity is always a good idea. But it is possible to have too much of a good thing and there is the risk a long-distance transmission project to never provide enough benefit to be worthwhile.

Because a long-distance electricity transmission project is a long term undertaking that may require decades to pay for itself, it is possible changing conditions and improving technology could convert what looks like a sound investment now into an albino elephant that never manages to pay for itself.

While large-scale renewables and long-distance transmission currently look like inseparable buddies, if the cost of solar and/or wind farms falls far enough, it will start making sense to build less transmission capacity and start overbuilding renewable capacity. But a more serious threat is if the cost of batteries falls to a very low level. Energy storage done dirt cheap will greatly reduce the economic return from long-distance transmission.

A More Interconnectored World

Thanks to low-interest rates and the variable nature of wind and solar energy generation, we’re going to see a lot of long-distance transmission capacity construction around the world over the next 10 years. How long this boom in electricity transmission capacity continues will depend on interest rates and the cost of energy storage.

If batteries fail to fall much further in price, we may see a world where long-distance transmission has fat cables able to provide plenty of power, allowing cheap solar electricity to light up locations where the sun has set. A world of extremely cheap battery storage may still have a lot of long-distance electricity transmission, but the cables won’t be able to provide as much power as they’ll have days to redress energy imbalances between regions thanks to copious battery storage.

Personally, I’m hoping we’ll see a lot of new long-distance transmission built in the short term, as that will help us more rapidly move away from coal and gas. If falling costs of battery storage then render it uneconomic, I’d still count that as a win.

I also hope that a world where electricity interconnectors between countries are common will be a place where people feel more connected with each other. At some level, we all want to connect, and for me, it’s at the level of massive electrical cabling. I hope countries relying on each other for electricity will help us see past our petty differences, encourage us to cast aside our intolerance, and see we’re not that different from each other. We’re just one big human family — and the Dutch.

Footnotes

- I’m not counting border towns that cheat by getting electricity from a state they’re not actually in. ↩

- Or 4 if you count 4,000 km of sugar cane train gauge in Queensland. ↩

- Australia is less lumpy than Antarctica — fight me. ↩

- A faux pas is when your mother’s boyfriend moves in, and she insists you call him dad. ↩

- A system that allows rich people to pay poor people to sit in the dark is one of the triumphs of the modern world. Our grandparents got humans on the moon; we get internationally traded darkness. ↩

Original Source: https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/renewables-long-distance-transmission/