Are Off Peak Hot Water Tariffs A Waste Of Time For Solar Owners?

Last week Finn got me into hot water. He did this by referring me to a study called::

“Analysis of electricity consumption and thermal storage of domestic electric water heating systems to utilize excess PV generation”

Let me translate that from Academeze into English for you:

Are electric hot water systems any good at soaking up excess solar electricity?

Here are some of the findings:

- Electric hot water systems average 25% of a home’s electricity use. That surprised me. It’s more than previous estimates I’d seen.

- If heat pump systems are ignored and only conventional electric hot water systems are considered, electric hot water averages 25% of a home’s electricity use.

- Electric hot water can act as a battery, storing energy from rooftop solar panels for later use.

- Even when no effort is made to increase solar electricity consumption, lots of the energy consumed by electric hot water systems can come from rooftop solar power.

The last point suggests that it may be cheaper for some households with solar panels to have their hot water systems on their regular tariff:

- even if a controlled load is available,

- even if the home’s solar system is relatively small,

- and even if they make no effort to control the hot water to match solar electricity generation.

After reading the study I was shocked at how little we know about Australian hot water energy consumption. I’m not saying we should spend a lot of money investigating this, but if the boffins at ANTSO get over $300 million a year, surely we can spare a little to look into the appliances that make up a quarter of residential energy use1.

In this article, I’ll tell you all the other interesting things I now know about Australian electric hot water, including the study’s main discoveries.

The Study Is Paywalled

The study is by Yildiz, Bilbao, Roberts, Heslop, Dore, Bruce2, MacGill, Egan, and Sproul. If you want to read it, I’m afraid it’s paywalled. If you’re not a university student, you’ll likely have to shell out money to Elsivier — an organisation that pays people who write papers nothing but charges others to read them.

The most positive thing I can say about that is, it’s good work if you can get it.

But if you want to read a science paper without paying for it, you can just pick whichever of the authors appears lowest on the academic pecking list based on how many letters they have after their name and send them an email saying:

“Dear [NAME], your paper [NAME OF PAPER] was recommended to me by [RANDOM NAME]. I would be very grateful if you could send me a copy of either it or an earlier draft. I promise not to use the information for evil.”

You’d be surprised how often that works.

[embedded content]

Who Did The Study Study?

The electricity consumption and solar energy generation of 410 households with electric hot water systems and rooftop solar panels were recorded over a full year in three capital cities. Locations and number of systems were:

- Brisbane: 250 systems

- Sydney: 100 systems

- Adelaide: 60 systems

The other capitals were left out. But given they can only study so much, these were the best cities to investigate. Homes in Melbourne and Perth often use gas hot water while Hobart only has around 225,000 people. Darwin’s population is even less and they don’t use much hot water in the Top End.

[embedded content]

Information From Solar Analytics

Information for the study was provided by Solar Analytics. They supply monitoring hardware and software for solar homes. They can also warn you if your solar system has a problem.

I recommend good monitoring systems as they have positive externalities. That is, they provide benefits for people other than their owners. For example, they make my life easier because if someone asks me for help with their solar power system, working out what’s wrong is a lot easier if they have good monitoring.

Not A Random Sample

Because owning Solar Analytics was required, the households in the study weren’t a random sample. This means the results don’t represent average households in Brisbane, Sydney, and Adelaide. Instead, they represent homes with Solar Analytics.

Because Solar Analytics costs money, people who have it are more likely to be well off with larger roofs, larger solar systems, and larger overall electricity consumption.

But because it doesn’t cost that much, I don’t expect the difference to be large.

I have no comment on whether Solar Analytics users are smarter, better looking, or smell nicer than those that don’t have it. These may be just rumours.

Australian Hot Water Consumption Is High

The study gave existing estimates for the percentage of household electricity consumed by electric hot water for Australia and overseas:

- Australia: 23%

- Europe: 14%

- USA: 18%

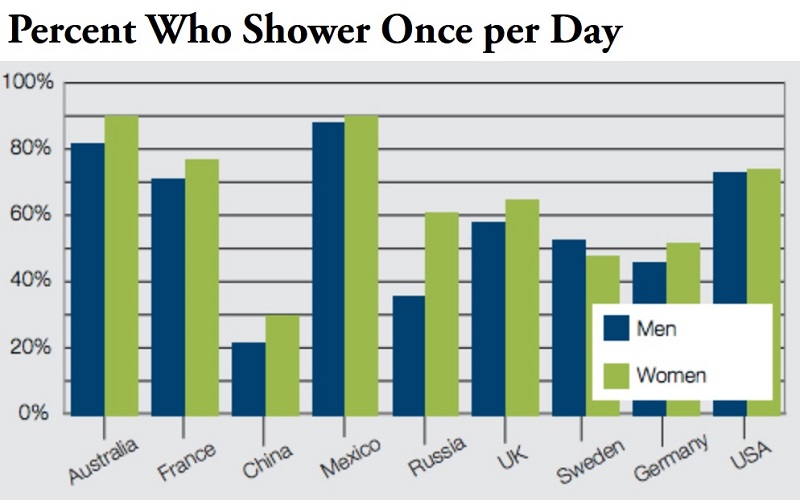

Australia has the highest percentage even though it’s the warmest of the three regions. This odd result is probably mostly explained by this…

(Image: The Atlantic)

Mexican males are the only people on the graph more fond of a daily shower than Aussie blokes. A fact that can be celebrated for just A$77.45 on redbubble:

There Are 2 Types Of Electric Hot Water Systems

The study looked at homes with either:

- Conventional hot water systems with a resistive element, or

- Heat pump hot water systems

Heat pumps are far more energy-efficient than resistive water heaters. The most efficient heat pump I know of gives 4.6 times more heat per kilowatt-hour than a conventional hot water system3. A mediocre heat pump may only provide twice as much heat.

While heat pump hot water systems are a great way to save energy, they’re only a small slice of hot water systems in use and 10% of systems in the study. But that’s more than I expected and shows they are gradually replacing conventional systems.

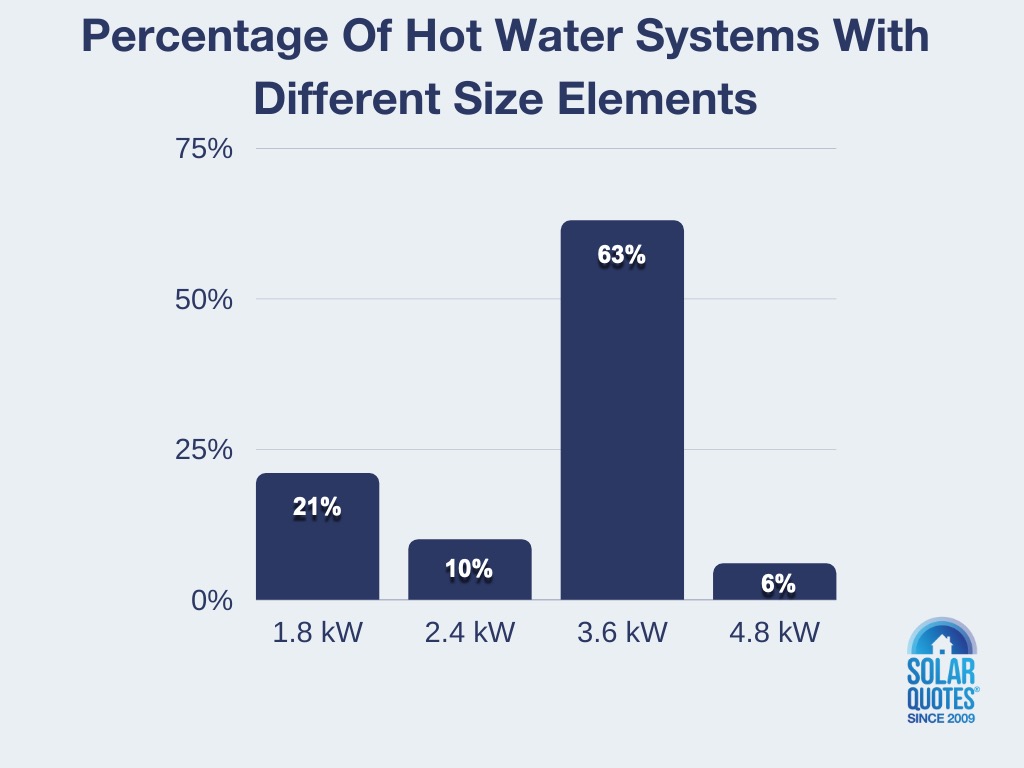

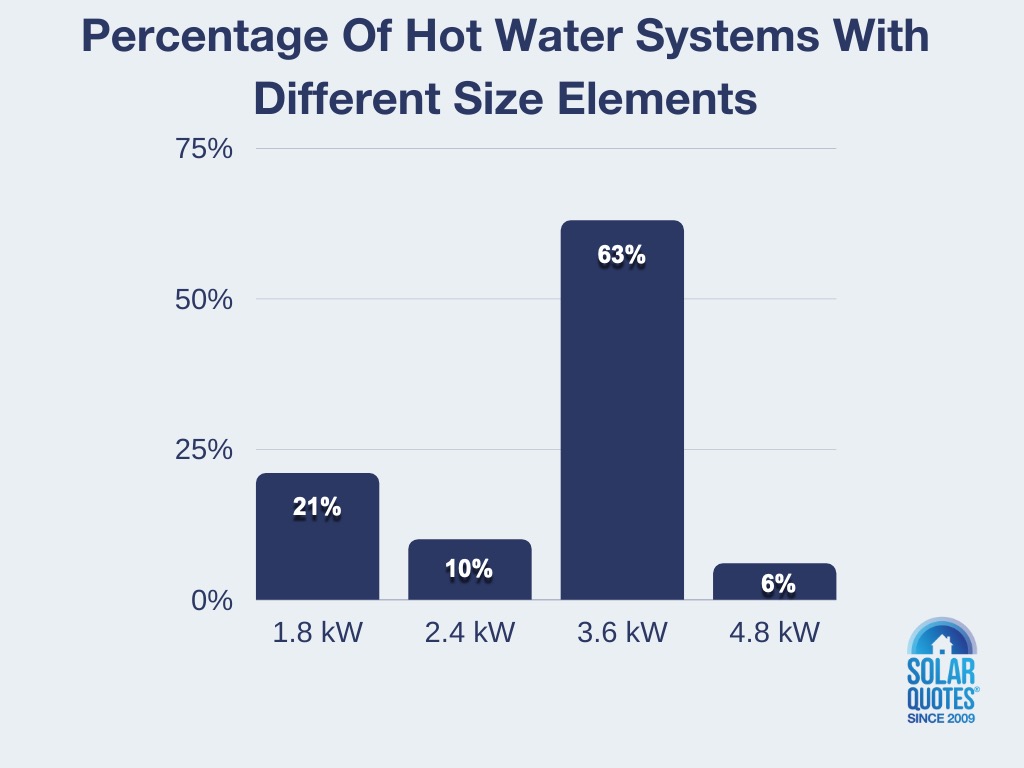

Power Draw

In operation, a heat pump hot water system generally draws 1 kilowatt or less. For conventional systems, it depends on the size of the heating element which can be:

- 1.8 kW

- 2.4 kW

- 3.6 kW, or

- 4.8 kW

As you can see below, 3.6 kW is by far the most common element size:

Some hot water systems have more than one element, but these weren’t mentioned in the study.

The larger the element size, the faster the water is heated. However, systems with larger elements often have larger tanks4 and so have more water to heat5.

Systems with smaller elements normally use a bigger percentage of solar energy. This is because they’re less likely to draw more power than the rooftop solar system provides. If you are getting a conventional hot water system, I recommend getting one with a smaller element where possible.

Hot Water Energy Consumption

From the information presented in the study, I could determine the households had…

- An average total daily electricity consumption of 24 kilowatt-hours.

- Average daily solar energy generation of 19 kilowatt-hours.

Total electricity consumption was well above the 14 kilowatt-hours I would expect for randomly selected homes with electric hot water systems.

Solar energy generation indicates the average rooftop solar power capacity studied is a little over 5 kilowatts. While not large for a new system today, it is roughly what I’d expect for a random sample of solar homes.

One thing the study clearly states is…

- The electric hot water systems consumed an average of 6 kilowatt-hours per day.

This means electric hot water systems consumed an average of 25% of total electricity use. This is more than any past estimate I’ve seen. If only homes with conventional electric resistance heaters are considered it’s even higher. If we assume heat pump hot water systems use one-third as much electrical energy, then homes with conventional systems use an average of 6.4 kilowatt-hours a day, which is 27% of total household electricity consumption.

My guess is the percentage is high because the overall efficiency of other appliances in the home has improved more than the efficiency of electric hot water systems.

Litres Of Hot Water Used

The amount of hot water used was not directly measured but was estimated to average 142 litres a day. The averages for the three cities were:

- Brisbane: 130 litres

- Sydney: 147 litres

- Adelaide: 153 litres

As expected, hot water use was higher in winter and lower in summer, with maximum consumption around 50% higher than the minimum. No significant difference was found between days of the week.

Regional Variation In Energy Consumption

Hot water systems consume more energy in colder locations, for three reasons:

- Water enters the home at a lower temperature in cooler regions.

- Storage tanks lose heat faster when it’s cold.

- But the main reason is people use more hot water when it’s cold.

Brisbane hot water systems used the least energy, while those in Sydney and Adelaide used similar amounts. The daily averages were:

- Brisbane: 5.6 kilowatt-hours

- Sydney: 6.3 kilowatt-hours

- Adelaide: 6.4 kilowatt-hours

Controlled & Uncontrolled Hot Water

There are two ways to run a hot water system:

- Controlled — Something other than the tank’s thermostat determines when the hot water system turns on and off6.

- Uncontrolled — Only the thermostat turns the element on and off.

Hot water systems can be controlled in a number of ways:

- A system on a controlled load receives grid power at a lower cost at times set by grid operators. Controlled loads may be called economy tariffs or off-peak hot water.

- A timer7.

- A relay that switches the hot water system on when the right conditions are met such as sufficient surplus solar generation.

- A switch installed next to the hot water system that lets you turn it on and off manually — but only a nutter would do this8. (Yes, I happen to have one of these switches…)

- Use a Solar PV hot water diverter to send surplus solar power generation to a conventional electric hot water system.

If a hot water system is on a controlled load, it won’t use any energy from your rooftop solar system — at least not as far as your electricity bill is concerned. The other control methods — timers, relays, and PV hot water diverters — are effective ways to increase the amount of solar energy used.

Western Australia is phasing out controlled loads and it is possible other states will do the same. When low priced controlled load tariffs aren’t available it increases the benefit from having a different method of control that increase the amount of solar energy used by hot water systems.

But even if a hot water system is uncontrolled, it’s still capable of getting most of its energy from solar, provided the solar power system is large enough and hot water consumption patterns are suitable.

Hot Water Electricity Consumption Patterns

There’s considerable variation in when hot water systems consume energy. It depends on hot water use and whether the systems are controlled or uncontrolled. Six main patterns of hot water consumption were identified:

- Morning and evening only

- Morning and evening with daytime

- Evenly distributed

- Morning

- Evening

- Late night

Not all of a household’s hot water use occurs during the time period its consumption pattern is named after. That just indicates when it mostly occurs.

In many homes, most hot water use occurs in the morning, less in the evening. This means an uncontrolled hot water system will switch on in the morning at a time it can take advantage of solar generation. It will also switch on in the evening when solar energy isn’t available, but its energy consumption won’t be as high. This can result in lots of its energy coming from solar panels. The amount will depend on:

- The solar system size — the bigger the better as the more solar power is available the less likely grid power will need to be used.

- The hot water system’s element size– here the smaller the better. The lower the power draw the more likely there will be enough surplus solar power. Because heat pump hot water systems have the lowest power draw, this makes them the best for maximizing the amount of solar energy used to heat water.

If hot water use and/or hot water system energy consumption mostly or entirely occurs when the sun isn’t in the sky, then little to no solar energy will be used. But on the bright side, if you have an uncontrolled hot water system, it’s not difficult to work out what sort of household you live in. It mostly comes down to when the most showers are taken.

Solar Energy Consumption Simulation

Information on the 410 households in the study was used to create simulations of how much solar energy hot water systems would consume. Because these were simulations and not direct observations, you may wish to take any conclusions with a grain of virtual reality salt.

But because the simulations are based on real-life results they should still provide useful information. I presume the authors of the study were very careful and diligent with their work. Just don’t ask me to check the results9.

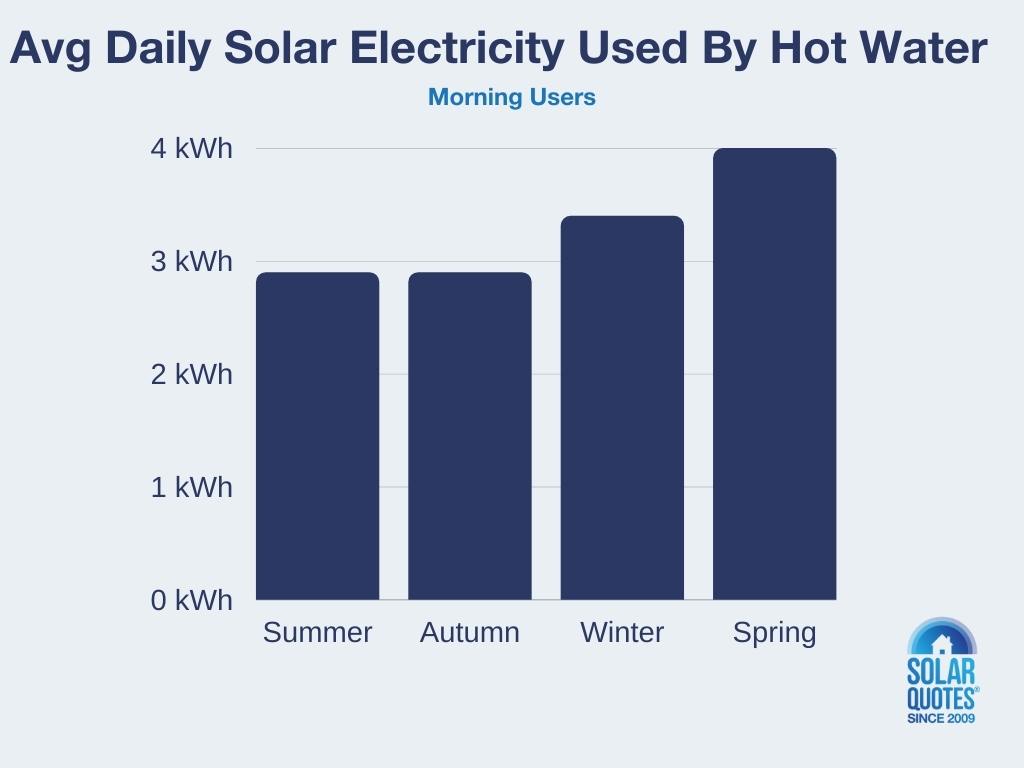

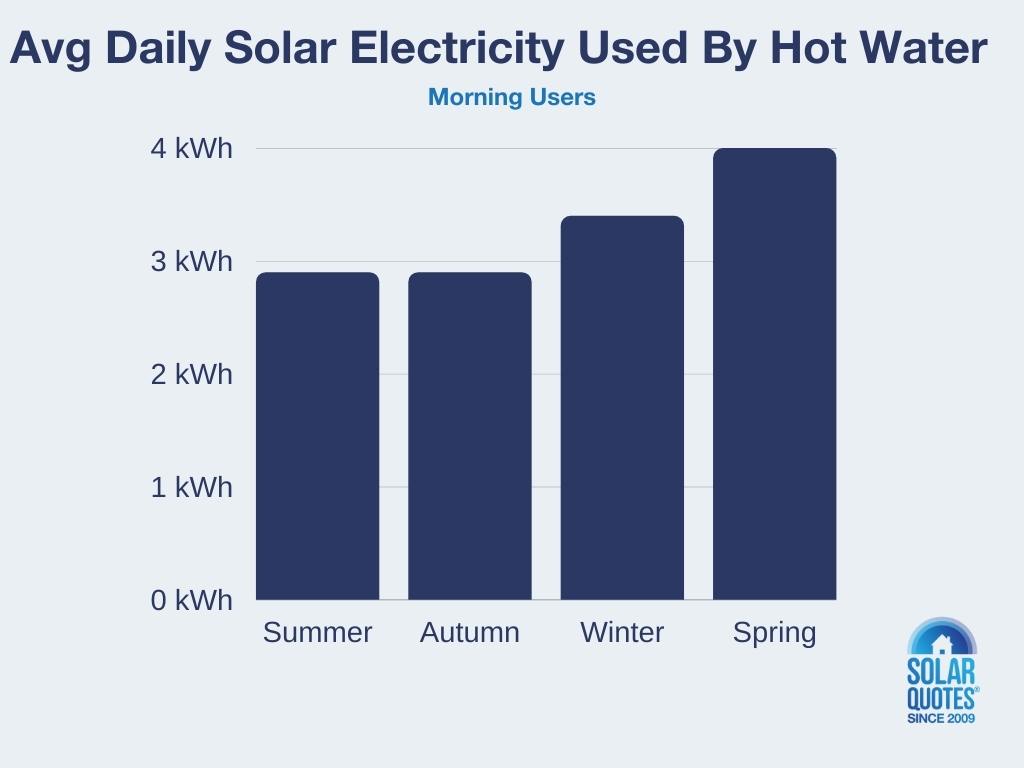

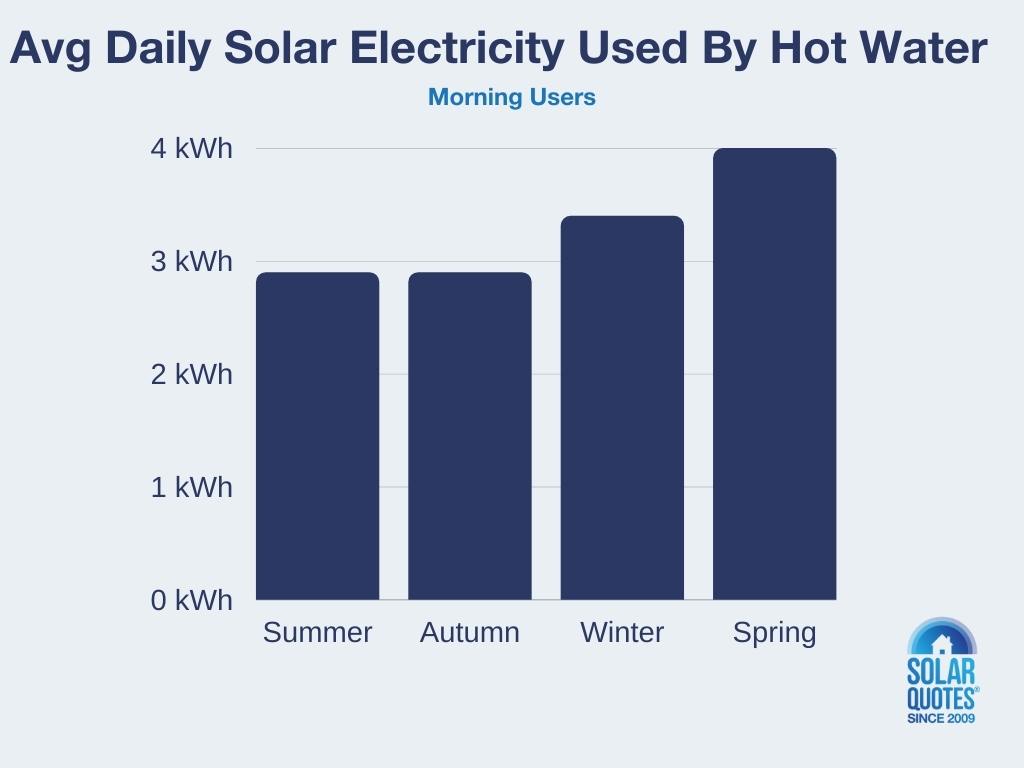

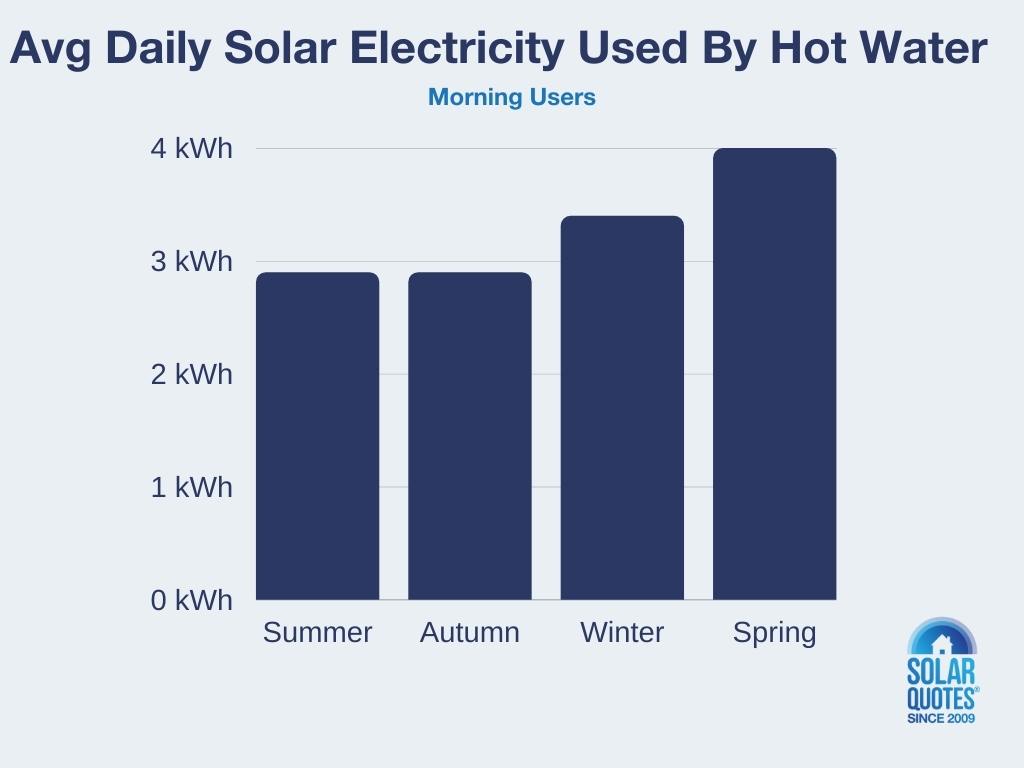

In a simulation, a home with the following characteristics was used:

- Hot water consumption mostly occurs in the morning.

- There is an uncontrolled conventional hot water system with a power draw of 3.6 kilowatts — the most common element size.

- There is a 3.6 kilowatt solar power system. This is tiny by today’s standards.

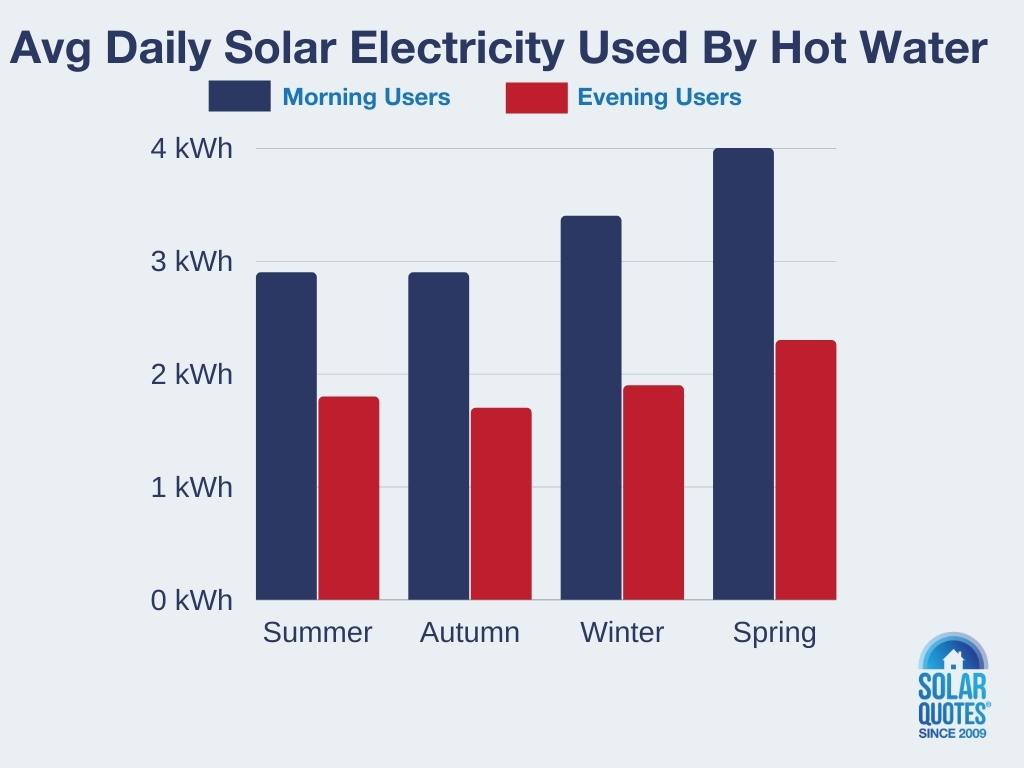

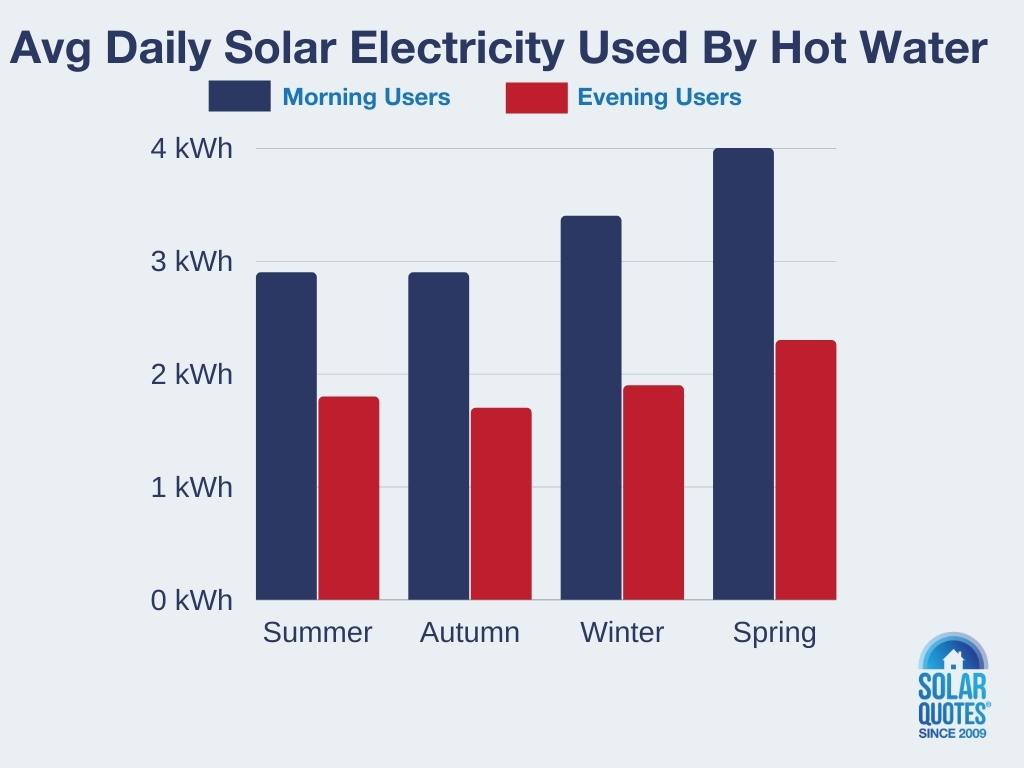

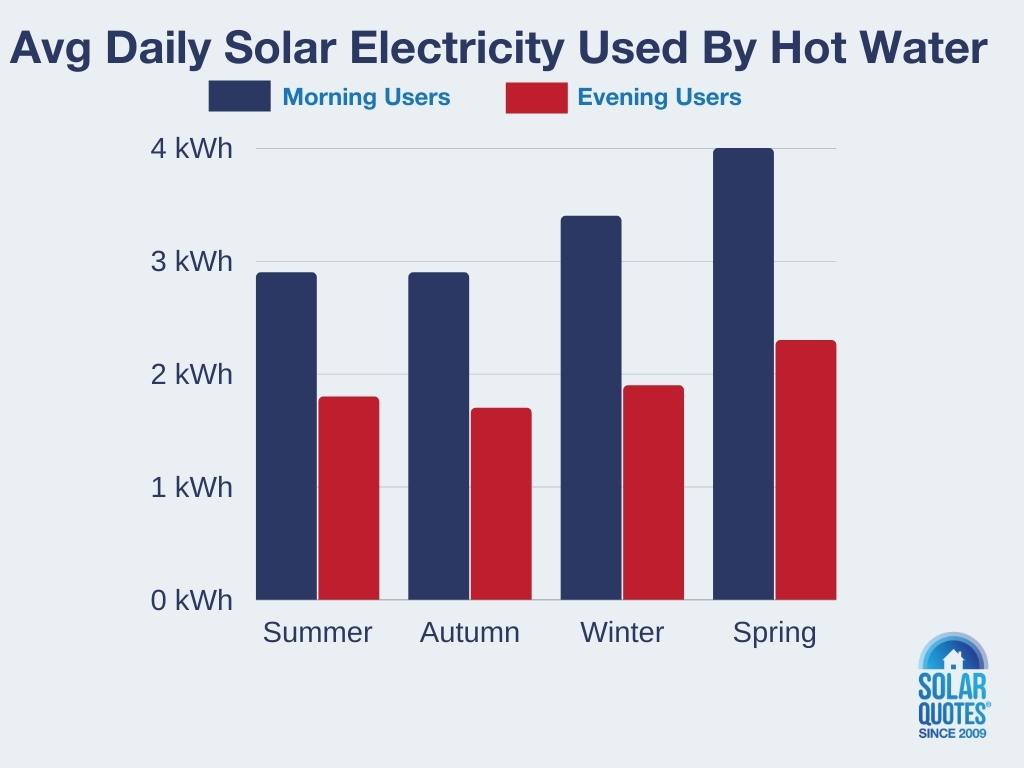

This resulted in 48% of the hot water energy coming from solar. An impressive amount for such a small amount of solar capacity. The graph below shows the average kilowatt-hour of solar energy used per day by the hot water system in each season:

While most solar energy is available in summer, hot water use is less and this resulted in summer having low average solar energy use. It was higher in winter, despite lower solar output, because more hot water was used. It was highest in spring thanks to good solar electricity output combined with high hot water use thanks to spring being colder than autumn.

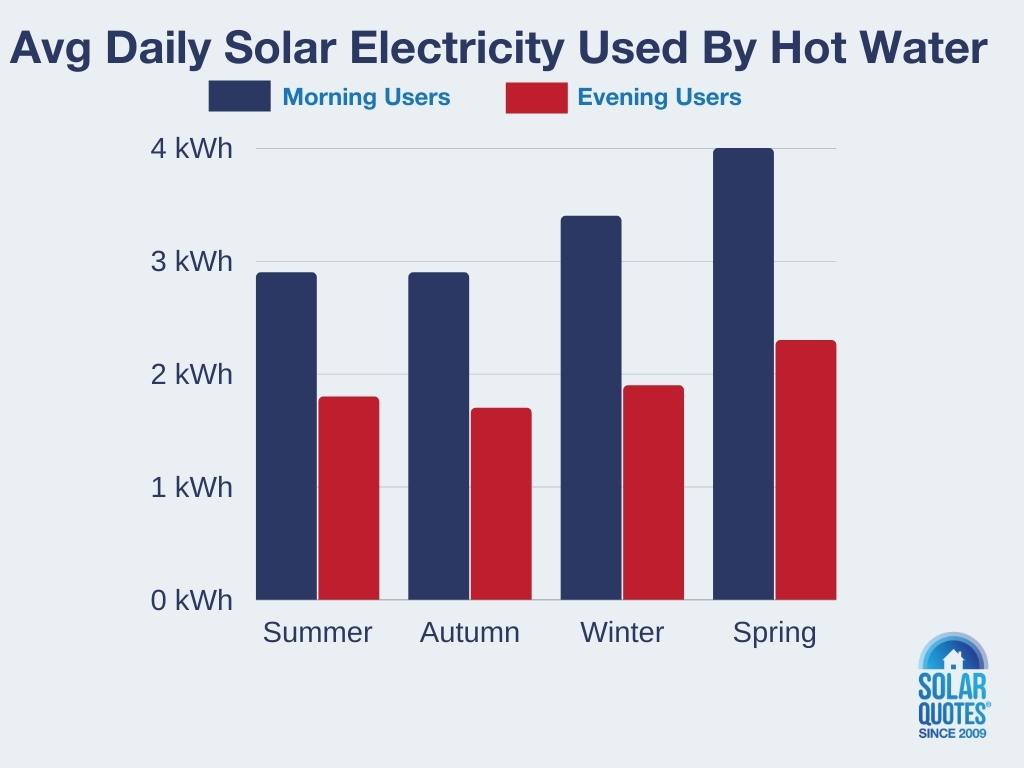

The amount of solar energy used heavily depends on the household’s hot water consumption pattern. If it’s not suitable it can be greatly reduced. The graph below shows what happens if the household has an evening hot water consumption pattern:

In this situation most of the hot water system’s energy use occurs at night, but some hot water consumption and energy use still occurs during the day allowing the rooftop solar system to contribute. For this consumption pattern 28% of the energy used by the hot water system is solar.

A Queensland Example

Provided an electric hot water system uses a sufficient amount of rooftop solar energy, it can be cost-effective for it to be taken off a controlled load even if no attempt is made to control when it turns on.

My parents are in regional Queensland and currently they…

- Pay 14.3 cents per kilowatt-hour for electricity consumed by their hot water system on a controlled load (tariff 31).

- Pay 21.8 cents per kilowatt-hour for grid electricity (tariff 11).

- Receive a 6.6 cent solar feed-in tariff for the energy they export to the grid.

- Have a hot water system that consumes an average of 2.7 kilowatt-hours a day.

At the moment, all energy consumption by their hot water system comes from their controlled load and costs them an average of 38.6 cents per day10. If their hot water system was taken off the controlled load and half the energy it consumed came from rooftop solar panels and half from the grid at a cost of 21.8 cents per kilowatt-hour, they would then effectively pay an average of 38.3 cents per day for hot water. A saving of 0.3 cents. This adds up to over $1 a year.

But that’s not all. In Queensland, homes have to pay a metering charge. Not having to pay this for a controlled load meter will save them 3.3 cents per day. All up, this would save my parents around $13 a year. Despite this windfall, my parents probably aren’t going to be in any hurry to call an electrician to remove their hot water system’s controlled load.

But if someone in Queensland was wondering if they should put their hot water system on a controlled load I’d tell them not to bother if they have solar panels.

My Conclusions

While the study was interesting, it hasn’t changed my advice on how to get cheap hot water. Just follow these steps:

- First, fill your roof with well-installed solar panels. As much as will reasonably fit and your budget allows.

- If you can afford it, get a reliable and efficient heat pump hot water system.

- If you get a conventional electric hot water system, try to get one with a smaller element.

- Put your hot water system on a timer to maximize its solar electricity consumption. Alternatively — especially if your hot water consumption is high — consider using a PV hot water diverter or a relay.

- Enjoy cheap hot water.

Footnotes

- While I’m sure studying ants is important, I’m certain they’ll still be around after we’re gone, which may not be long if we don’t clean up our energy act.

- Clearly an Australian academic

- Note sometimes the efficiency of heat pump hot water systems are exaggerated as only the efficiency of the heat pump is given without taking into account other energy consumption by the unit.

- The most common tank size is 315 litres.

- But because hot water rises to the top of the storage tank where the outlet is, a larger element generally means you don’t have to wait as long until you can have a shower if you run out of hot water, regardless of how large the tank is.

- Although the thermostat will always cut the power if the water gets to temperature

- It’s well past time all hot water systems came with one of these built-in.

- Note water in a storage tank has to regularly reach at least 60 degrees to stop legionnaires disease, so a nutter who isn’t careful could wind up nibbled on by the parrot of death.

- I studied statistics so long ago if we wanted to do a T-test, we first had to invade Ceylon to get some.

- My mum says it’s worth it.

Original Source: https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/electric-hot-water-solar/