Canberra Battery Test Centre Final Report: Only 1 Of 26 Batteries Fault-Free

For eight years, the Canberra Battery Test Centre lived up to its name and tested batteries. From 2016, they put 26 home batteries through their paces. If I had to sum up the results in a single word, it would be:

Atrocious

If I had to sum it up in 2 words, they would be…

Mostly atrocious

Of the 26 batteries tested, only one was fault-free and operated as it should have from the beginning to the end of testing. That’s a success rate of under 4%.

On top of the bad news that only one battery is reliable, I am saddened to tell you that the Canberra Battery Test Centre has shut down for good.

To rub in just how closed they are, their website went offline while I was in the middle of writing this article. It caused me some consternation, but fortunately, ARENA has archived all 12 of their reports here. It’s a bloody good thing they have since it’s your money that paid for those reports.

In this end-of-an-era article, I’m going to provide…

- A brief review of how well or how badly all 26 batteries tested performed. It’s mostly badly.

- The best and worst results.

- A more focused look at the test results for home batteries made by Sonnen, LG Chem, Tesla, BYD, and Alpha ESS, all of which have sold well in Australia.

- Information on round-trip efficiency.

- How battery prices have changed.

- Essential advice on how to buy a decent home battery.

But first, I’ll give you a list of articles I’ve written in the past on the Battery Test Centre and briefly describe their testing procedures.

Previous Articles On Battery Test Centre

Over the past six years, the Canberra Battery Test Centre has published 12 reports, and I’ve written eight articles on them. Here are the seven you’re not currently reading, in chronological order:

- Worrisome Results From Canberra’s Battery Test Centre

- Canberra Battery Test Centre Update — BYD Battery Comes Out On Top

- 6th Canberra Battery Test Centre Report — 61% Of Tested Batteries Faulty

- The Canberra Battery Test Centre’s 7th Report: 83% Faulty

- Battery Test Centre 8th & 9th Reports: Many Home Batteries Still Unreliable

- 75% of Home Batteries Faulty In Long Term Battery Testing

- Canberra Battery Test Centre Phase 3 Results: Zero Batteries Problem Free

As you can tell from the titles, the results weren’t encouraging. They grew worse as testing continued, and more batteries failed.

One Of Each Type

Before I summarize the miserable results of battery testing, I’ll mention they only tested one of each battery. This means we can’t draw any firm conclusions on the reliability of individual batteries. The results provide evidence but not conclusive evidence. What is clear is home batteries, in general, are not reliable.

Even Noah got two of each kind at his Euphrates Animal Test Centre. (Painting by some Pennsylvanian Hicks.)

Accelerated Battery Testing

For most homes, the average amount of energy a home battery stores each day will be less than the battery’s maximum capacity. But special circumstances, such as joining a Virtual Power Plant (VPP), may raise the daily average above 100%. Every time a battery is fully charged and fully discharged, it’s called a “full cycle” or “cycle” for short. For convenience, it’s often assumed a home battery will be (fully) cycled an average of once per day.

The Test Centre undertook accelerated testing to get an idea of how long each battery will be able to perform one full cycle per day. For most batteries, this involved fully cycling them three times per day. For each cycle, the battery would be charged over three hours, fully discharged over 3 hours, and given two hours of rest. This allowed the equivalent of three years of daily cycling to be crammed into one. Some batteries couldn’t handle this and were tested at a less rapid pace. These included all the non-lithium batteries.

This type of testing is not perfect as it works the batteries harder than they would be in real life, which can increase capacity loss. But it is the best way to get an idea of how well the home batteries will hold up long-term in a limited testing period.

The Test Centre also altered the test room’s temperature to reflect typical temperatures in a Sydney location; but did not expose them to the extreme highs and lows a battery installed outdoors would occasionally suffer. The highest temperature was 36ºC, and the lowest was 10ºC.

To make the information more useful, I’ll convert the results to how many years the battery would have operated if cycled once per day. Where possible, I’ll also estimate battery capacity after ten years of daily cycling, assuming the rate of loss remained constant. If you don’t see this information, it’s because the Test Centre couldn’t measure it accurately — or at all in a few cases.

Also, note this squiggle “~” means “approximately”.

26 Batteries Tested

There were three phases of battery testing involving a total of 26 home batteries. The battery chemistries were of four different types:

- Lithium: 21 batteries

- Lead-acid: 2 batteries

- Zinc-bromide: 1 battery

- Sodium nickel chloride: 1 battery

There were eight batteries in Phase 1, 10 in Phase 2, and eight again in Phase 3.

Phase 1: Testing of these eight batteries began in May 2016.

- CALB CA100: After installation, a defective battery cell was discovered and replaced within a week. This battery under-performed and provided less energy than it should have each cycle. The capacity loss was excessive. After the equivalent of 4.1 years of daily cycling, it was down to ~76%. At this rate, it would be down to ~42% after 10 years.

- Ecoult UltraFlex: This was a lead-acid battery, but a supposedly advanced sort called a “lead-carbon” battery. It developed a fault and was replaced. It later failed and testing did not continue. Capacity loss for either the original or the replacement was not given.

- GNB PbA: This was a lead-acid battery. It had difficulty accepting full charge, likely due to sulfation, which is a common problem when you stick lead in sulfuric acid as lead-acid batteries do. Because it could not be cycled rapidly, it only completed 480 cycles. While capacity loss appeared significant, no figure was given.

- Kokam + ADS-TEC: This battery was from a company that had been developing lithium batteries for 18 years at the time of installation. It failed so early no meaningful results were obtained. It was not replaced.

- LG Chem RESU 1: This home battery would derate and supply less energy at higher temperatures. After the equivalent of 3.2 years of daily cycling, it failed. At this point, its battery capacity was 78%. This loss was excessive as, at this rate, it would be at around 55% after ten years: less than the 60% minimum its warranty promised. It was replaced with a newer model for Phase 2 testing.

- Samsung AIO: Worked well until it developed a fault after the equivalent of 7 years of daily cycling. Battery capacity was on track to be 65% after the equivalent of 10 years of daily cycling.

- Sony Fortelion: No faults. Around 81% of capacity left after the equivalent of 10 years of daily cycling.

- Tesla Powerwall 1: The Powerwall 1 could not be controlled by the Test Centre and so charged and discharged at its maximum rate. This caused it to charge and discharge in 2-hour periods instead of 3. After a prolonged shutdown, it developed a fault and died. Even allowing for its faster charging and discharging, its capacity loss was excessive and on track to be 41% after 10 years.

Phase 2: Testing of the 10 Phase 2 batteries began in July 2017.

- Apha ESS M48100: Had difficulty supplying as much energy as it should have, especially in warmer temperatures. Alpha ESS said the battery pack was abnormal and collected it. They then declared they would no longer participate in testing. Capacity loss was at ~78% after the equivalent of 2.4 years of daily cycling. At that rate, it would be at ~9% after 10 years, assuming it worked at all after degrading so much.

- Ampetus Super Lithium: The battery had a fault and was returned to Ampetus for repairs. This did not fix the underlying problem, and testing was discontinued. It appeared many, or all Ampetus batteries had this problem and the manufacturer, Sinlion, did not honour its warranty. As a result, Ampetus went bust.

- Aquion Aspen: The Test Centre was unable to get this battery to function. The manufacturer went bust during installation, and it was not replaced.

- BYD B-Box LVS: This home battery functioned well at first, but then its rate of capacity loss increased. After the equivalent of 4.8 years of daily cycling, it was at ~64% capacity and on track to be at ~25% after 10 years. It then developed a fault, and BYD replaced it with a newer module used in Phase 3 testing.

- GNB Lithium: No operational faults, but disastrous capacity loss with ~37% capacity after the equivalent of 5.3 years of daily cycling.

- LG Chem RESU HV: Failed and was replaced. Excessive capacity loss in 2nd unit with ~75% capacity after the equivalent of 5.6 years of daily cycling. At this rate, it would be at ~55% capacity after 10 years.

- Pylontech US2000B: No faults but excessive capacity loss with ~77% remaining after the equivalent of 7.8 years of daily cycling. This suggests it would be at ~57% after 10 years.

- Redflow ZCell: Replaced 4 times. Once due to electrolyte contamination and three times due to leaks. Final unit at ~93% capacity after the equivalent of ~2.2 years of daily cycling. While the capacity loss was less than some lithium batteries, it was excessive for this battery chemistry.

- SimpliPhi PHI 3.4: The Test Centre was unable to accurately measure the battery’s performance. SimpliPhi said the inverter settings they originally recommended were actually a bad idea and had caused the batteries to be discharged too far, causing them to become faulty. A refund was given rather than a replacement.

- Tesla Powerwall 2: It either became faulty immediately after installation or arrived in that state. It was first repaired and later entirely replaced. Capacity was ~79% after 6.9 years of daily cycling, which suggests ~70% after 10 years.

Phase 3: Testing of these batteries began at the start of 2020, giving limited testing time.

- BYD HVM 11.0: Suffered two faults which put it out of action for months. No sign of capacity loss after the equivalent of 3.2 years of daily cycling.

- DCS PV 10.0W: Only supplied around 75% as much energy as it should have per cycle. Disastrous capacity loss with ~57% remaining after the equivalent of 3 years of daily cycling.

- Fimer React 2: One minor fault. Acceptable capacity loss with ~86% remaining after the equivalent of 4.8 years of daily cycling, putting it on track to be at ~71% after 10 years. Highest round trip efficiency of all home batteries tested.

- FZ SoNick: This was the only sodium nickel chloride battery tested. It suffered two faults, and its capacity loss was acceptable at 92% after the equivalent of 2.8 years of daily cycling. If that loss rate continued, it would be ~71% after 10 years.

- PowerPlus Energy LiFe Premium: Only provided around 60% as much energy per cycle as it should have. Capacity loss appeared acceptable as, if it operated normally, it may have been on track for ~75% capacity after 10 years.

- SolaX Triple Power: Developed a fault, and the entire battery was replaced. The capacity loss was on track for 88% after 10 years, but the uninterrupted testing period was too brief for confidence.

- SonnenBatterie: Two of four battery modules were replaced. No sign of battery capacity loss after 2.2 years of daily cycling.

- Zenaji Aeon: Only provided around one-third as much energy per cycle as it should have. Impossible to accurately measure capacity loss.

No Communications Link — Linked To Poor Results

Most batteries had a communications link between their Battery Management System (BMS) and their inverter. This “closed-loop control” allows the batteries to tell the inverter what to do so their performance can be fine-tuned. Other batteries had “open-loop control” where there is no communication link to the inverter. This leaves the inverter to blindly guess how the batteries should be charged and discharged.

The home batteries without a communications link were:

- Ecoult UltraFlex (A communication link was installed, but it failed.)

- GNB PbA

- SimpliPhi PHI 3.4

- DCS PV 10.0W

- PowerPlus Energy LiFe Premium

- Zenaji Aeon

In addition, the Ampetus Super Lithium communication link didn’t work well.

While the overall results of battery testing were poor, the ones without communication links generally had the following problems:

- Accurate test results were hard to obtain, as It was difficult to measure how much charge was in these batteries.

- They all supplied less stored energy than they should have per full cycle — sometimes far less.

- While it was difficult to measure capacity loss, with one exception, it generally appeared excessive.

Having a communications link is no guarantee a battery will perform well but given the test results, I do not recommend getting a home battery without one.

Safety The Only OK Thing

The best thing I can say about the Test Centre’s horrible overall results is — none of the home batteries failed in a way that was dangerous to homeowners. There were no electrocutions, fires, or clouds of toxic gas. We can’t be certain all systems would have remained safe if testing continued, but it is a good sign.

Winners…

Of the 26 home batteries tested, there was only one clear winner. A single battery worked without a fault for a testing period that simulated 10 years of daily cycling and did not suffer excessive capacity loss. By the imaginary power vested in me by my fictitious position as Battery Pope, I hereby declare the champion of batteries to be…

The Sony Fortelion

As the only one that was problem free, it beat all other challengers. This battery was one-in-a-million — or to be more accurate, it was one-in-26. After what approximated 10 years of daily cycling, it still retained 81% of its original capacity. Its success is not too surprising, as Sony brought the first commercial lithium battery cell to market in 1991.

This was a premium home battery that was very expensive and counts as evidence that you have to pay for it if you want the best. But be cautious — just because a battery is expensive doesn’t guarantee you’re receiving the best. However you still have to expect to shell out for quality because, while you don’t always get what you pay for, you never get what you don’t pay for.

The bad news is it is no longer possible to buy Sony Fortelion batteries. I’m not aware of anyone selling them in Australia. So we have a winner that, in a practical sense, doesn’t do anyone any good.

The closest thing to a runner-up is the Fimer React 2. It managed the equivalent of 4.8 years of daily cycling while only suffering one minor fault and was on track to be at 71% capacity after 10 years of daily cycling.

Nothing else didn’t suffer a major fault of some kind or excessive capacity loss. I suppose I could say the Samsung AIO did well for the equivalent of 7 years of daily cycling before failing, but that’s still only 70% of the 10 years its warranty allowed, which is not what I call good.

This is my Battery Pope regalia. (Circuits are displayed in gold with dendrite motifs upon shoulders and chest.) I don’t have a photo of me wearing it because, after placing the order, I had to wait three months for it to arrive. Then I had to send it back to be altered four times. Finally, when I arrived for the photo shoot, I suffered a complete wardrobe malfunction.

…& Losers

The worst battery managed to supply no energy at all. The Aquion Aspen saltwater battery failed completely. The only thing it succeeded in doing was showing up. The Test Center was unable to get it working and Aquion went bust while they were trying to install it, leaving them with no repair, refund, or replacement for the complete dud of a battery.

This serves as a warning to anyone buying a home battery from a new manufacturer without a proven track record — or an established one in an uncertain financial position. Unfortunately, it’s not easy for homeowners to establish the financial health of companies.

There are a number of contenders for second worst. The Kokam Storeax is in the running, as it failed without replacement after so little time, the Test Centre said no meaningful information was collected.

The Ampetus/Sinlion Disaster

One large loser was the Ampetus Super Lithium battery. This was manufactured by the Chinese company Sinlion and sold by Ampetus in Australia. The Test Centre had trouble installing the battery and returned it to Ampetus. After updating its firmware, they sent it back, and the Test Centre was able to get it working. However, the underlying problem was not fixed, leading to the battery failing.

This fault was also present in other batteries Ampetus sold, and Sinlion decided not to honour its warranty and replace or repair them. This left Ampetus responsible for the faulty batteries they’d sold, and they went bust.

Here is what the Test Centre said on the situation:

This tragedy is a warning to anyone thinking of buying or selling home batteries.

The evil Sinlion squares off against the noble Fortelion. (Yes, Sin-lion is a brunette.)

Big Battery Brands In Australia

Most of the batteries tested are now no longer available or have been superseded by newer models. This makes the results far less useful than they could be for people planning to buy a home battery, but I’ll give more details on the test results of batteries from manufacturers that have sold well in Australia and may continue to do so in the future. In roughly chronological order, they are:

- Sonnen

- LG Chem

- Tesla

- BYD

- Alpha ESS

Sonnen

Sonnen originated in Germany and was the first to produce home battery systems for use on-grid. Their battery in Phase 3 testing required two out of four battery modules to be replaced. After these repairs, the Test Centre had enough time to give it the equivalent of 2.2 years of daily cycling. In this time, it suffered no noticeable capacity loss.

It’s disappointing that Sonnen, which has been making home batteries longer than anyone else, failed to supply one that worked without a problem. On the bright side, if it does work, its capacity retention is likely to be excellent. Sonnen promises that if it’s cycled 10,000 times within 10 years, it will retain at least 80% of its original capacity. A battery that’s cycled daily will only hit 3,650 cycles after 10 years.

Sonnen says they fully cycled one of their batteries 28,000 times, and it retained 65% capacity. These appear to be tough home batteries, so I wouldn’t be surprised if they still have 93% or more capacity remaining after 10 years of daily cycling.

The SonnenBatterie had the lowest round trip efficiency of all the lithium batteries tested. This is not a major problem, and I presume it’s a side effect of the system’s constant and careful battery monitoring to ensure low capacity loss.

Sonnen is now owned by Shell, which is a large company. I presume Shell will be around for a while, but they are overexposed to fossil fuels, which is a clear risk. Also, they’re Dutch.

LG Chem

The large South Korean manufacturer, LG Chem1, has sold a considerable number of home batteries in Australia. They had two batteries tested, and neither performed well.

LG Chem RESU 1: This battery tended to supply less energy than it should have when discharged at warmer temperatures that simulate summer conditions. It failed after the equivalent of 3.2 years of daily cycling. At this point, its battery capacity was ~78%. If capacity loss continued at that rate, it would be at 52% after 10 years, which is unacceptable and less than the 60% minimum promised by its warranty. It was replaced with an LG Chem RESU HV, which was used in the 2nd Phase of testing.

LG Chem RESU HV: This battery failed after around 14 months and was replaced. By the end of testing, the replacement had operated for the equivalent of 5.6 years of daily cycling and was at -75% capacity. If this continued, it would be at around 55% after 10 years. In my opinion, this is, once again, unacceptable capacity loss.

LG Chem is a large company, and in the past, I would have recommended them for this reason, as it looked like they would be around long-term to honour their warranties. But they have had large-scale recalls of batteries, and I have heard too many complaints about them being slow to replace home batteries and address problems for me to recommend them now.

Tesla

The Test Centre examined two Tesla batteries:

Tesla Powerwall 1: Despite a lot of hype, hardly any Powerwall 1s were installed in Australia — the only country where any were sold. Because the Powerwall 1 didn’t allow the Test Centre to control it, it would charge and discharge at its maximum rate, which was a two-hour charge and two-hour discharge instead of the 3 hours used for other lithium batteries. This may have increased its capacity loss. It failed after 7 years of operation.

Even allowing for its faster charging and discharging, capacity loss was excessive. It was at ~59% after the equivalent of 7 years of daily cycling. If this had continued, it would have been at around 41% after 10 years.

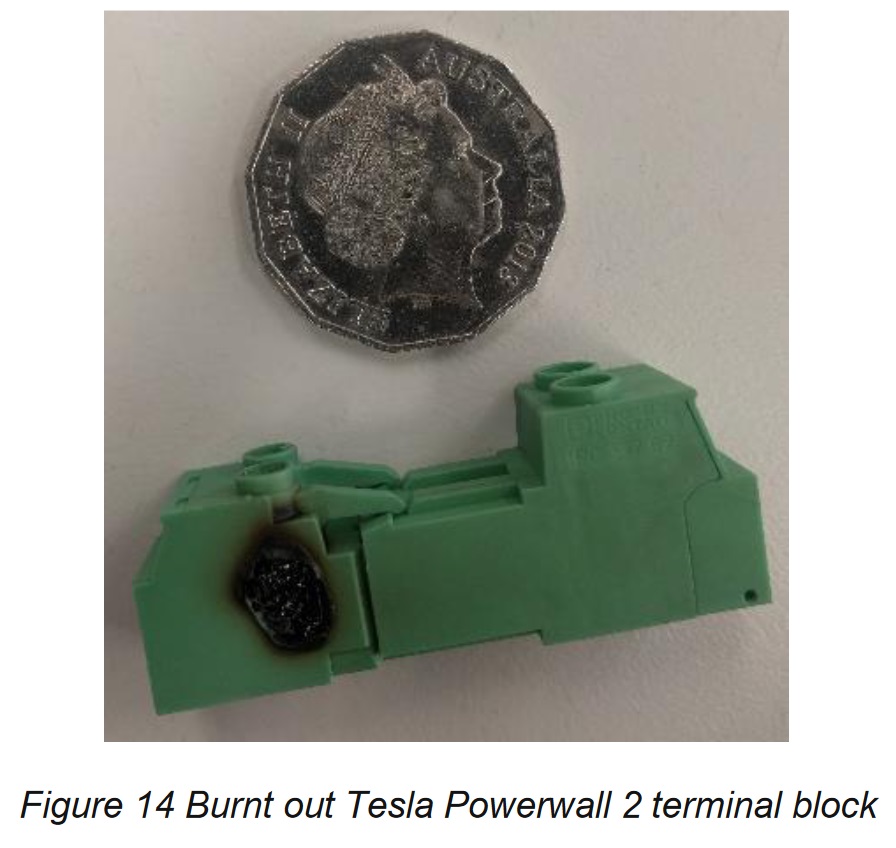

Tesla Powerwall 2: After the first Powerwall 2 was installed, a burned-out terminal block was found. Its cause was not clear and may have arrived in this condition:

This photo is from page 24 of the Battery Test Centre’s 3rd report.

After this was repaired, the unit didn’t undergo testing because the Test Centre couldn’t directly control it. After around 15 months, a fault was detected, and Tesla replaced the battery. Testing began 18 months after the first Powerwall 2 was installed, with Tesla controlling the charging and discharging.

After the equivalent of 6.9 years of daily cycling, it’s capacity was ~79%. At this rate, it would be at ~70% after 10 years. This isn’t great, but it isn’t terrible either. Provided the supporting electronics continue to work, lithium batteries with 70% capacity could have many years of useful life left in them.

Tesla is a large company and hopefully will still be around in the future to honour warranty claims. But it faces increasing competition from other manufacturers in the home battery and EV markets. Unfortunately, the CEO is having a very public mid-life crisis that he can’t resolve in the traditional way by buying a sports car, as he already owns several sports car factories.

Elon Musk’s erratic behaviour and penchant for engaging in unsupported exaggeration — or lies, as we call them in Australia — makes it difficult for me to recommend this battery.

[embedded content]

While I don’t trust Tesla as a company, their current Powerwall 2 is one of the better solar battery systems available on the market. People who get them usually get a system that works.

At this time, the entire home battery industry trips off my Grandmother Rule, which means I wouldn’t recommend any home battery to someone who wants a reliable product with a high likelihood of receiving quality warranty support in the future. But Tesla doesn’t yet break my Crazy Cousin rule. This covers someone who is technically competent enough to understand what they are getting into and is willing to tolerate the risk.

BYD

Two BYD batteries were tested:

BYD B-Box LVS: This home battery operated without problem at first, and after the equivalent of 2.7 years of daily cycling, it was at around 91% capacity. If this continued, it would be at 67% after 10 years, which wouldn’t be great but would still be usable.

But the loss accelerated, and after the equivalent of 4.8 years of daily cycling, it was down to around 64%. If this more rapid battery loss continued, it would completely fail before 10 years. The Battery Management Unit failed and was replaced, and later one of its four battery modules indicated it had developed a fault. BYD stated all four modules were faulty and provided a more up-to-date replacement battery that was used in the 3rd Phase of testing.

BYD HVM 11.0: This suffered two faults. These were fixed, but they did prevent the battery from being used for several months. It was only given the equivalent of 3.2 years of daily cycling before the Battery Test Centre closed down, but it showed no measurable sign of capacity loss in that time.

BYD is a giant Chinese manufacturer that produces, among other things, electric cars and buses. Hopefully, they’ll be around long-term to honour their warranties. While their two batteries didn’t do well in testing, they are probably still among one of the better home battery brands to buy. This is because of their considerable battery experience, large size, and because it looks like they want Australia to be a long-term market for their products.

Alpha ESS

Alpha ESS had one battery tested, which didn’t perform well:

Apha ESS M48100: The Test Centre used a climate-controlled testing room and would vary the temperature to mimic seasonal variation. At warmer temperatures, the battery was unable to supply as much energy per cycle as it should have. Alpha ESS said this behaviour was abnormal and collected it. Alpha ESS later said they would no longer participate in testing.

Alpha ESS has sold a considerable number of solar battery systems in Australia. They are a lower-cost home battery. When batteries are sold at a lower price, inadequate money may be put aside to pay for after-sales service, warranty support, and product recalls. This article describes a horrific lack of customer support from Alpha ESS for a faulty product. Alpha ESS says they will do better in the future. I’ll need to see strong evidence of this before I can recommend them.

Round Trip Efficiency

Batteries are charged with energy, and the stored energy is discharged when required. There are always losses from this process. The amount of energy put into a battery divided by the amount taken out is its round-trip efficiency. It’s normally given as a percentage.

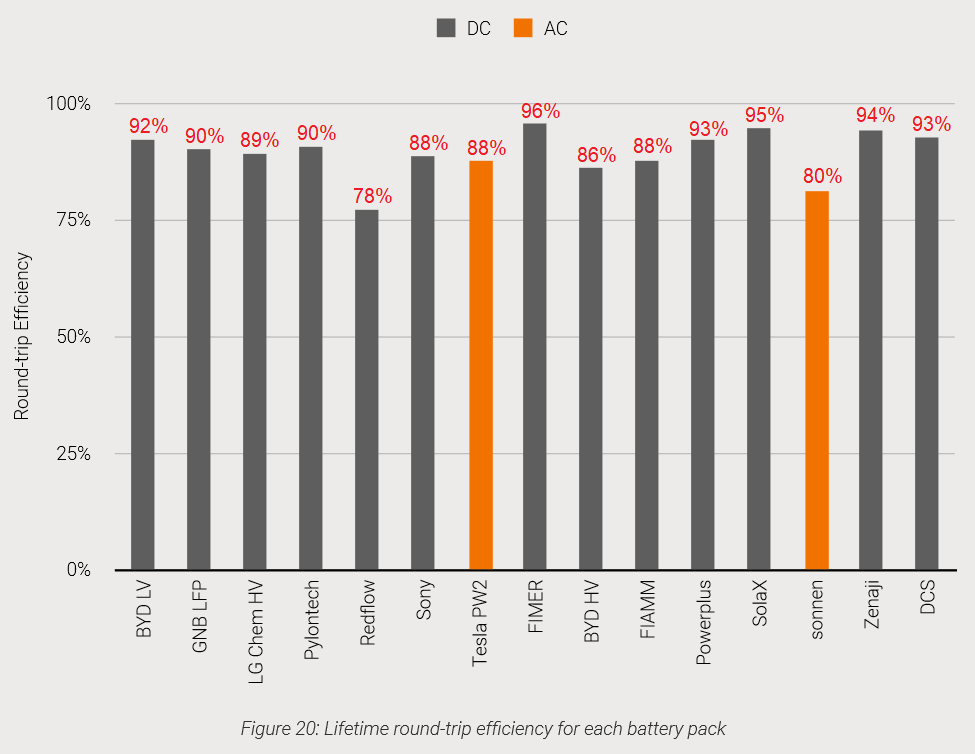

Overall, for the 15 home batteries where round trip efficiency figures were given, the results were fairly good, as the graph below shows:

This graph is from the Test Centre’s final report but — in an attempt to improve its usefulness — I added the percentage figures in red, which are based on the length of the bars.

The two systems in orange — the Tesla Powerwall 2 and the SonnenBatterie — were AC coupled. By their nature, these will tend to have lower than average round trip efficiency figures. In testing, the Powerwall 2 did well for an AC coupled system, while the Sonnen had the lowest efficiency of any lithium battery. The only one on the graph with worse round trip efficiency was the Redflow ZCell, which has very different battery chemistry.

Home Battery Prices — Little Change?

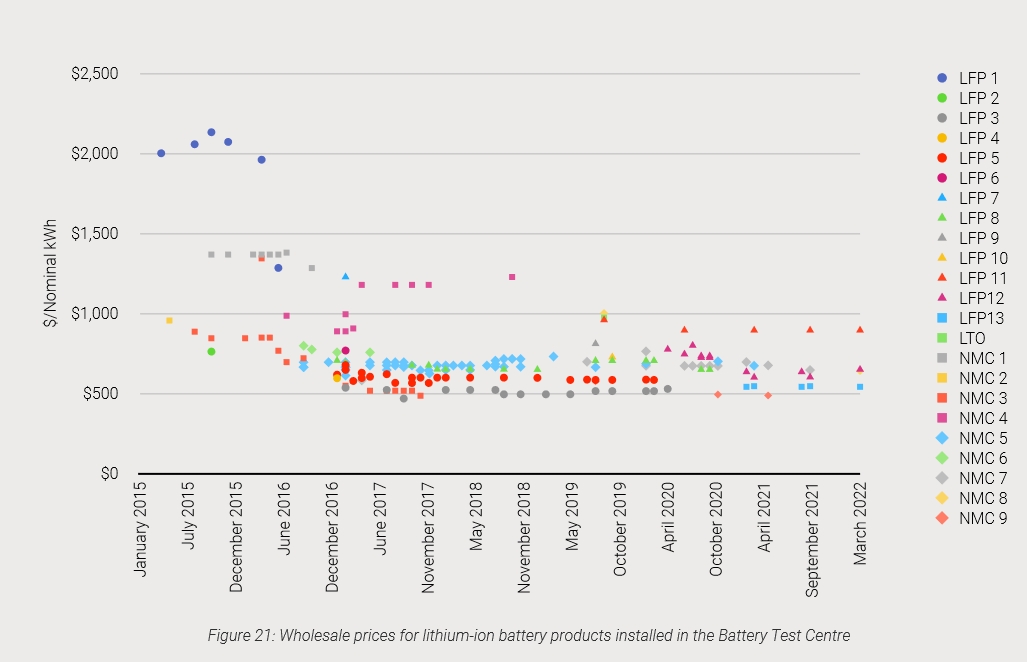

This graph shows what the Canberra Battery Test Centre paid per kilowatt-hour for 23 tested batteries, but doesn’t give their names:

If you were determined, you could go through Test Centre reports and make good guesses on which home batteries cost what. But I wasn’t really determined, so I didn’t.

It looks like there has been little change in prices since the middle of 2017. But this overlooks inflation, which has been around 11% since then. So if a battery was $700 a kilowatt 5 years ago and is $700 a kilowatt-hour now, in real terms it has become 11% cheaper. This year solar battery prices have generally increased. A notable example is the Tesla Powerwall 2. A major contributor to this has been increased costs of raw materials, particularly lithium.

A major reason why home batteries are still expensive is that they’re so unreliable. For every one that’s sold, a considerable sum has to be set aside to cover the potential cost of replacements and repairs. As reliability improves, prices will come down. The price of producing battery systems is also certain to decrease in the future, but when it will happen is not certain.

Advice For Buying A Solar Battery

After reading how only one battery out of 26 made it through testing without a problem, you may be wondering what you can do to be certain your home battery purchase will be problem free?

The short answer is, you can’t.

Regrettably, home batteries simply aren’t at the same level of development as other household electrical devices. They’re not like dishwashers, air conditioners, or solar systems where you can have them installed and expect to work without problem for many years — provided you buy something decent. Even if you buy a high-end solar battery system, there is no guarantee it will be problem free. The Canberra Battery Test Centre has provided plenty of evidence of this.

But while there is no way you ensure you will have a problem-free home battery, there are steps you can take to improve the odds and reduce the amount of stress you’ll suffer if and when a problem does occur:

- Choose a good manufacturer.

- Choose an excellent installer.

- Check the battery will do everything you expect.

- Consider buying a home battery and solar power system separately.

A Good Manufacturer

Choosing a battery from a good manufacturer is obvious advice. The hard part is knowing who the good manufacturers are. I recommend looking for the following:

- Long-term battery experience.

- A good reputation for quality and reliability.

- Demonstrated good customer service and timely warranty support.

- An Australian Office — If they don’t have one, the importer will become responsible for the manufacturer’s warranties, so you’ll have to trust them.

- A high likelihood of being around in the future to provide warranty support.

An Excellent Installer

Your installer not only has to set up the battery, but they also have an obligation to ensure it works and keep it working for its warranty period2. Whoever you paid has a responsibility to provide you with a working battery system, and they must ensure it continues to work for a reasonable period. If you choose an installer that’s reluctant to live up to their obligations, you’re potentially in for a world of trouble.

You can check online reviews to see what sort of after-sales service installers provide. It’s not enough to just check if the batteries they install have problems because, as we’ve seen, problem-free home batteries are rare. But you can check if issues are addressed rapidly and to and to customers’ satisfaction.

Check It Will Do What You Want

If there is a battery you are considering buying, do your research and — before you buy it — check with the installer it will do everything you will expect. This can include:

- The number of kilowatt-hours of energy it will supply when fully charged.

- Expected capacity loss.

- Will it provide backup? If so, how much power and what parts of your home will receive it?

- If a blackout happens at a random time, will there always be some charge in the battery to provide backup?

- Can the battery charge from rooftop solar panels during a blackout?

- Can you join a Virtual Power Plant (VPP)?

- How many years will the warranty last?

Under Australian Consumer Guarantees, a product must do everything salespeople tell you it will do. But if you don’t ask, you may have a nasty shock if you end up sitting in the dark because you didn’t get the version of the home battery that provides backup in a blackout. If you email an installer, you can get answers in writing.

SolarQuotes has a large number of blog posts and other resources to help you in your research and help you understand the answers your installer gives you – for example; Finn’s 101 guides to understanding, buying and owning solar batteries.

Buy The Battery Separate From Solar

I recommend buying your home battery separately from your solar power system. This is because if you buy your battery and solar system bundled together and the battery side of things turns out to be a disaster, it can greatly complicate having the battery removed and receiving a refund. There have been situations where households have had a functioning solar system removed from their roof because it was purchased with a defective home battery.

I’m not saying it never makes sense to have a battery and solar system installed at the same time, but it may make sense for them to be separate purchases. Exactly how much sense this makes I can’t say because I’m not a lawyer – but I suggest installers look into selling batteries and solar this way.

The End Of An Era

As the Canberra Battery Test Centre is no more, I was going to declare this to be my final article on it. But then I realised in a decade, I’ll probably want to look back and laugh at how only one home battery out of more than two dozen pulled off the amazing feat of actually working as promised,

Hopefully, it will be a funny “haha” kind of laugh because 99% of home battery installations will be problem-free and not the insane cackle I’ll have if, in ten years’ time, it has only improved to one in a dozen.

Footnotes

- In December 2020, LG Energy Solution was launched incorporating the LG Chem battery business. Since that time, “Chem” has been dropped from LG battery names. ↩

- Under Australian law, they can potentially be responsible for it for longer than the written warranty, but I would not count on this for solar batteries. ↩

Original Source: https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/battery-testing-final-report/