Battery Degradation Part II: How To Measure It

Image Credit: Selectronic Australia

All batteries degrade over time. The battery warranty specifies the maximum degradation you can expect – typically over ten years. But how do you know how much your battery has actually degraded?

Part one of this post helped you understand why and how a battery degrades and how you can minimise degradation (TL:DR; don’t let it get too hot or cold).

In this post, I’ll explain how you can measure your battery degradation and how manufacturers will measure it to verify any warranty claim. I’ll also give you some tips on choosing a robust battery for your home.

How Do You Measure A Battery’s Degradation?

If there’s any suspicion about the performance or longevity of your home battery, the first step is simply observing your battery monitoring. I much prefer this way of measuring real-world performance because you can observe over time and get a really clear picture. Numbers don’t lie, and graphs are great for visualising what’s happening.

Funnily enough, I don’t know of any home battery monitoring software, first or third party, that gives you a battery degradation figure. If you know of any, please let me know in the comments.

It’s obvious why battery manufacturers don’t want to be transparent about battery degradation – the sad truth is the less you know, the less likely you are to make a warranty query1. But I’m surprised no one has made a third-party app that hooks into your battery monitoring and gives you a degradation trend. These apps are common for EV batteries, but I can’t find any for home batteries.

How To Measure Your Battery’s Degradation Using Monitoring

To measure your battery degradation – you are at the mercy of your monitoring software. In this example, I’ll look at my friend Sean’s twin Tesla Powerwall installation using only the Tesla app.

I’ll start by looking for a 24-hour period where the batteries fully cycle once. Sean’s Powerwalls are set to a 15% reserve level, which means charging from 15% to 100% and vice versa makes a full cycle.

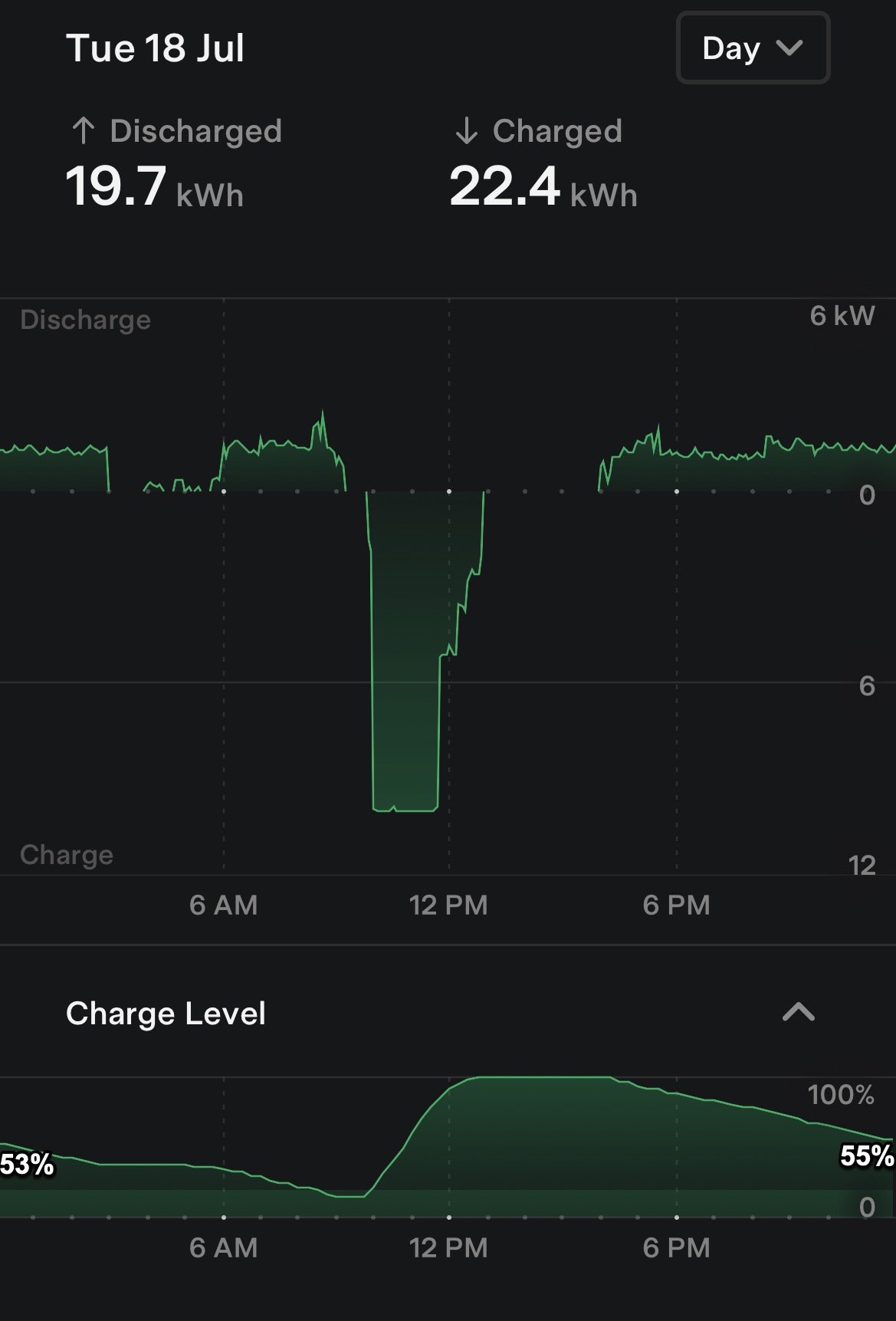

July 18 looks good:

The batteries charge from 14% to 100%, adding 86% of capacity.

The batteries initially discharge from 53% to 14%, lossing 39%. Following a top up they drop from 100% to 55% – losing 45%. So they discharge a total of 86%.

So I’ve found a 24 hour period where the 2 Powerwalls charge up by 86% and discharge by 84%.

To add 86% took 22.4 kWh of electricity. I will normalise that to 84% so it matches the discharge capacity:

- 21.9 kWh was required to charge 84%.

- 19.7 kWh was delivered by discharging 84%

So 2.2 kWh of electricity was lost in the process – a 90% roundtrip efficiency – what I’d expect from Powerwall.

In terms of capacity degradation, a brand new Powerwall is sold with 13.5 kWh of usable capacity, so Sean’s twin battery should store 27 kWh when brand new (and the ambient temperature is 25ºC).

84% of 27 kWh is 22.7 kWh.

So a brand new pair of batteries in ideal test conditions should discharge 22.7 kWh.

19.7 kWh is 87% of 22.7 kWh, so the batteries are at 87% of their specified capacity by this test. Not bad.

Things to note:

- This was a winter day; the temperature overnight dropped to under 10ºC, which would hurt performance.

- It was a nice steady discharge averaging 1.15 kW of power draw. Two Powerwalls can deliver 10 kW of power, so that’s about a 0.1C discharge rate. Expect a faster discharge to generate more heat and inefficiencies.

- This pair of batteries comprises one brand new Powerwall paired with one 5-year-old Powerwall, so the older one should account for most of the degradation. How you measure the degradation of battery modules of different ages that are connected is a problem I can’t offer a simple solution for.

- The Tesla app lets you download the data – so you could do a better analysis by busting out Excel and combining 2 x 24h periods to watch the battery fully charge, then fully discharge, instead of discharge-charge-discharge.

- It would be easy to build a spreadsheet to automate this – I’ll ask Kim, our Excel whizz, to consider making one. Watch the blog for updates.

- You’ll learn more about your battery’s degradation by tracking how much energy is discharged over time than by a one-off snapshot. It would be nice if Tesla (and all the other vendors) showed degradation curves in their app – or an enterprising app developer launched a Powerwall Health Check app that hooks into the open Powerwall API and trends capacity over time.

How Does A Manufacturer Measure A Battery’s Degradation?

It’s fine and dandy for you too decide that your battery’s degradation is out of spec, but the manufactirer will want to verify your measurements with a more controlled experiment.

Having read battery warranty pdfs until my eyes bleed, I have found some makers very prescriptive in testing, but it’s simple enough.

- Maintain this temperature,

- charge to this threshold,

- discharge with this load

- until you reach this other threshold,

- within this time frame.

Write down the numbers you get at the end. Good documents spell it out, but to be honest, some of the warranty conditions, and the exclusions in particular, aren’t what I’d call fair and reasonable.

Redback for the win

One of the cheapest systems I’ve looked at has one of the longest warranties, while the Australian-developed Redback battery system has the simplest. Their warranty is 10 years, and when I reached out to ask if there’s any catch they just said:

“nup, mate she’s ten years.”

IP-rated doesn’t necessarily mean weatherproof. This garden ornament shows why I always insist batteries go somewhere cool and dry.

An example of a manufacturer’s documented capacity test

If you consult the Pylontech warranty documents, they read like this :

If any testing of the Product’s capacity is required, the testing must occur in the following conditions

a) The test is based on single US series battery module.

b) The ambient temperature of the Product must be 25℃±2℃

c) The initial temperature of the battery pods must be 25℃±1℃

d) Constant voltage(54V) constant current (0.2C-rate) charge till all the cell voltages are above 3.50Vdc or until charge current drops to less than 1 amp.

e) Constant voltage(43.5V) constant current (0.2C-rate) discharge till battery low voltage protection cut-off.

Warranties: Some Examples Are Batshit Crazy

Sorry, but I have to share my pain. This is a (thankfully superseded) warranty condition for QCells Batteries:

– Operating Temperature: If the temperature of Product (Cell/module temperature) is higher than 45ºC but lower than 50ºC or lower than or equal -10ºC but higher than or equal -15ºC for charging and, higher than 50ºC but lower than 55ºC or lower than or equal -15ºC but higher than or equal -20ºC for discharging, apart from the reduction in energy throughput caused by the degradation of cycle life due to the lapse of the operating period, the amount of energy throughput and/or the number of cycles of Product under warranty shall be reduced by (0.0065)%p per 1 minute.

Is it calculated in capacity lost per minute and degree outside spec? Or just per minute over/under the threshold? I guess that’s why they want it internet-connected because to quote the current version of the warranty:

“From the moment the energy throughput reaches the number in the table above, Qcells has the right to terminate the warranty of Product”

This is really where Australian Consumer Law is a saviour. If you’ve followed the instructions, no matter what clauses and excuses they might put in the fine print, a manufacturer must make good on whatever the marketing claims. It’s called an ‘express warranty’ and comes down to the fact a reasonable customer can expect reasonable performance for a reasonable cost.

CSIRO want a star rating for home batteries

Even the CSIRO has reached out to us trying to get a handle, not on how, but what to test batteries for. They’re concerned about the efficiency of residential battery/inverter systems because a 13 kWh battery cycled once daily might consume 3 kWh per day as internal losses, which is quite significant. My example above showed 2.2 kWh lost during a full cycle – so they are in the ballpark

There is no star rating system or testing for residential batteries, but the CSIRO thinks there should be. I like that idea. Devising a reasonable set of tests is their next challenge, but I’d point out that if you have a large solar PV system, solar energy is cheap enough to “waste”.

At SolarQuotes We Try To Make Batteries Comparable

In our growing list of hybrid inverter reviews we have extracted numbers that makers give you and put them into context so you can compare apples with apples, almost. Some have unique features, but this is an example of our metrics:

- Nominal Warranty: 15 years – 60% capacity remaining / 29.5 MWh throughput per 6.86 kWh module

- Usable Capacity: 6.5 / 13 / 19.5 kWh

- Approx retail: $12,000 + installation for 6.5 kWh

Throughput means the kWh you have recovered from the battery, ignoring that you’ve probably lost some energy along the way as electrical and chemical losses. Note that if you run a full cycle once per day, this “15 year” battery expires prematurely. In car terms, you’ve run out of kilometres before years on the warranty.

- Throughput limit @ 1 full cycle per day: 11 years 9.5months

For a value proposition, we divided the upfront retail price by the size of the battery. It’s bang for buck.

- $-per-usable-kWh: $1,846

For a different value, we have divided the retail cost by the number of cycles you’ll get under warranty, or durability for dollars.

- $-per-warranted-kWh : $0.40 @ 1 cycle per day / $0.20 @ 2 cycles per day

Your Installer Is Your First Port Of Call

Unless it’s a significant performance issue, your installer won’t have hours to spend on your data. We really need good software to run desktop audits like that. Your installer should be happy to explain how to interpret monitoring, but it’s in your interest to take notice of the performance.

Enthusiasts are the best and worst friends of installers. They examine new products and raise issues all too readily sometimes. However, I’ve got first-hand experience with a GCL ‘ekwb’ battery that was a little shy on its numbers. The customer logged the data and lobbed it back to GCL. They admitted it wasn’t doing what it said on the tin, and sent me out with a second battery to hang on the wall in parallel. It didn’t measure up by some hundreds of watts, so they gave him 5000 more watts to enjoy. Happy days.

So What Solar Battery Should You Buy?

- Start by examining your solar monitoring or a decent analysis of your power bill. Solar Batteries make the best sense when you have surplus solar to fill them – or access to a very cheap daytime tariff. They’re not a magic bullet, so you should understand your usage and tariffs, and how a battery will work with them before dropping a lot of money.

- I wouldn’t look at something suspiciously cheap or that only promises 50% capacity at ten years, not when you can get an exceptionally good warranty for the same expense.

- There are many other options, higher price points, or chemistries and features that may be important for your particular requirements. Check our other pages for reference:-

If you want the safest and most durable thing I’ve ever seen, then Lithium Titanate batteries from Zenaji or equally Arvio are probably it, combined with the best inverter of course. Still, you’ll need a healthy budget and an appetite for Australian-made hardware.

Footnotes

Original Source: https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/how-to-measure-battery-degradation/