Second Life Solar: Making The Most Of Used Panels

If you’re replacing a small system with a bigger and better one, what does an ethical way to dispose of your old equipment look like? Read on while we detail a couple of ways old solar can still lead a useful life.

Realistically speaking, used solar equipment is nigh on worthless in Australia due in equal parts to first-world labour rates and the STC incentive scheme, which effectively puts new glass on your roof for free.

We’ve detailed it before, but if you have to remove a solar power system, it’s often better to replace it with a new one than to reinstall legacy technology.

Gumtree Geezers Beware

Remember paying $12,000 for your one-kilowatt, six-panel solar power system? You’ll need to subtract two zeros for a quick secondhand sale. It’s increasingly rare that people need like-for-like replacements, so inverters get scrapped, sadly, for cents per kilogram.

Panels may be worth more depending on age. Some people offer $10 or $20 each for any old modules. They are packed roughly in shipping containers and sent to developing countries.

Though this can be a great reuse of resources, it has also been argued that it is just dumping e-waste on people ill-equipped to recycle it properly. New panel prices are getting so low that it’s hardly worth shipping them now.

Newer modules retired from bigger systems are of some value to off-grid type applications. The 20 panel, 5 kilowatt systems that are too modest for a modern house these days can actually make grand battery charging systems for a weekend campsite or low-budget tiny home.

Solar Depreciation Is Worse Than Luxury Cars

A bloke I know bought a new Aston Martin a few years back, with complimentary flights to England, so he could watch them build it.

Amazing the trinkets you get when the trade-in value for your low mileage, supercharged V8 Jaguar means you burnt $145,000 in four years. My heart bleeds for him when he complains it’s too shady for solar at his house.

With rules changing continually, solar technology moves faster than any performance car.

Connection approvals, updated Australian and IEC international standards, warranty rules, plus the need for skilled labour to make installation compliant means new solar panels are hard to give away once they’ve been screwed to a roof.

Even Electricians Pay Solar Installers

Electricians all understand the wiring rules (AS3000) but industrial, mining, process control, line work, or domestic house bashing are all crafts of their own. They call for different standards, meaning qualified electricians will seek out help for specialties they’re not tooled up to work with.

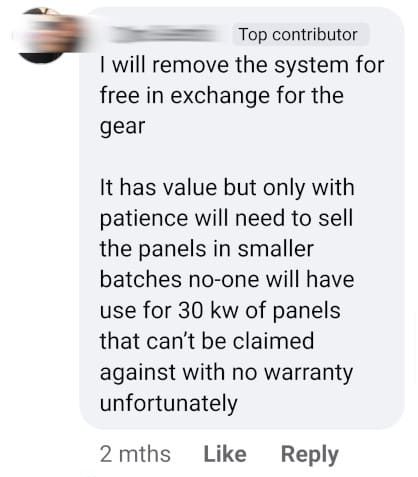

Posted recently on one of my professional groups. It’s a great example of a budget system being oversold by an end user, and an electrician confusing Megawatts with Kilowatts.

A qualified & insured local solar installer making a well-reasoned offer to professionally remove a system & cart it away. He was happy not to win it.

The punter who bought this asset above should be aware that it can still cost real money to reinstall legally.

Electrical work over 50 volts AC or 120 volts DC must be undertaken by qualified people.

DIY enthusiasts won’t get insurance for their houses if they’re working above these thresholds, but as we’ve written before, a campervan can be a good learning experience. Even those contemplating a tiny house could skirt the rules legally.

For charging a 48 volt battery, wiring this monster array up in 44 pairs of panels might technically work. That would be a ludicrous arrangement if you’re aiming for 30kW of solar though.

Where originally this system was 4 strings and one inverter, for 44 strings you’d need no less than six Victron 150/100 MPPT regulators.

At $700 each, that’s $4200 before you’ve bought 88 fuses, 88 plugs or a single metre of cable. A classic case of why DIY isn’t cheap.

Old Solar Is Great For Little Jobs

Small solar panels are poisonously expensive and often poor quality. You can pay $7 per watt if you’re mad enough.

Whereas an old 200watt panel for $20 equates to 10 cents per watt, so if you have the physical space there’s no reason why your pond pump, electric gate opener, stock fence energiser or garden lights don’t deserve a panel with 10 times the capacity you need.

A typical solar powered gate opener with 22VOC panel

Control Is Essential

Most rooftop solar panels put out around 45v or 38v: that’ll literally cook a battery if it’s not regulated.

Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) is a basic type, but better units use Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT).

While an MPPT is more expensive, it will cope with 45 volts input and 14 volts output without drastically cutting the conversion efficiency.

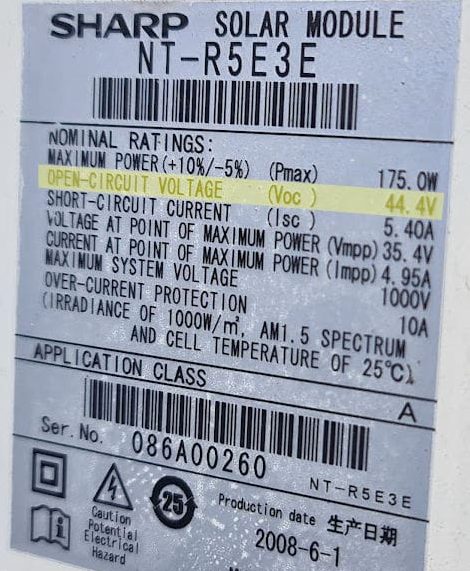

Take Note. The key specification to take note of is the Open Circuit Voltage (VOC) of the panel, to ensure it doesn’t exceed the rated input for the regulator.

If you are looking at cheap regulators/charge controllers on eBay, and the VOC specification is vague or hard to find, don’t buy it.

Something like the Victron unit pictured below will cope with 55VOC, but even with reputable brands, the fine print explains it’s only suitable for 24v batteries if you’re using a 38+VOC household solar panel.

This demonstrates the problem with PWM-type regulators: they work simply by switching on and off for a fraction of a second. Even though it’s fast, repeatedly exposing the battery to full panel voltage is still quite rough and will shorten the life of the battery.

Victron BlueSolar PWM Light 12/24v-10a will handle most single domestic solar panels.

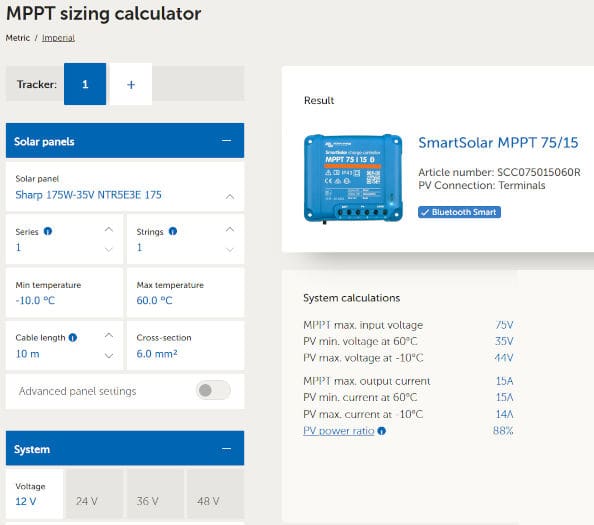

A decent and durable solution needs something like a Victron SmartSolar MPPT 75/15. There’s an online calculator to choose one.

Put a panel brand and wattage into this widget and it’ll help select hardware.

Better yet, with this unit you can pull up nearby and check the system is working via Bluetooth without needing a meter, screwdriver or screen.

A Word Of Warning

If you find some old solar panels that are sort-of uniform mahogany-brown colour, made by Kaneka, Mitsubishi, Schott or others, they could be thin-film solar panels.

They offer about half the wattage per square metre of a crystalline solar panel and very high open circuit voltage, which sadly means they’re not good for much, especially battery charging.

For instance a 100w Mitsubishi thin film is 1.4 x 1.1 metres, putting out 0.9amps at 110VOC ie 65watts/m².

1kW of Mitsubishi thin films. 2008:05:28 13:43:52

A contemporary Sharp 175w crystalline panel is typically 1.6 x 0.8 metres, putting out nearly 5amps at 44VOC, ie 136w/m².

I love the fact Sharp would date the panels they make.

Two wires from the solar panel to the regulator which is hiding under that green cover, then two more wires to the battery (preferably with a fuse in line), is about as simple as it gets.

An all-black 200watt panel cobbled up to a couple of fence posts.

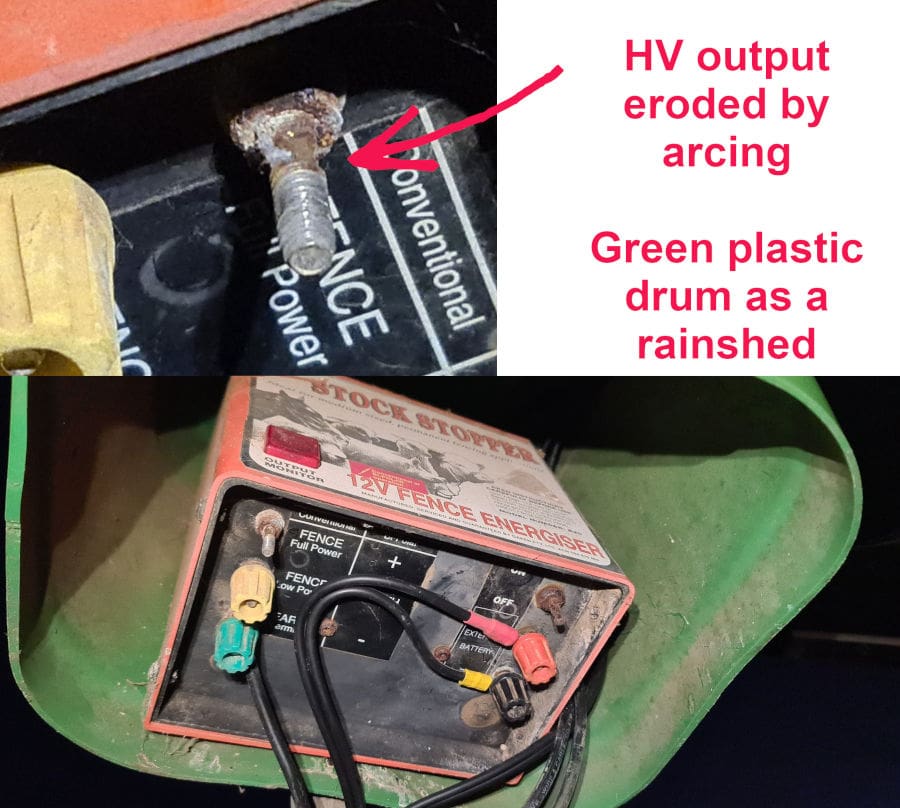

This closeup shows why clean connections are essential. A stock fence energiser turns 12 volts from a battery into short pulses of 7500 volts!

Although the current is tiny, it’s able to bridge gaps and slowly gouge out poor connections like this one. On the 12-volt supply side, this connection would have stopped working years ago.

Farming involves many skills, like engineering weatherproof enclosures and diagnosing burnt electrical connections.

There are plenty of guides available on how to size and connect a solar panel to charge a battery. If you can identify the dangerous end of a screwdriver and tell red from black, there’s a good chance you can make this example above work at your place.

Stay tuned. If I can raid the SolarQuotes kitty, we’ll do a quick step-by-step demonstration of how to do it.

Original Source: https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/second-life-used-panels/