Does It Make Sense To Build Electric Cars In Australia?

A few weeks ago, I wrote about how ACE-EV plans to open a factory and produce tens of thousands of electric vehicles per year in Adelaide.

I’m hoping it will happen because I was impressed when I took their electric cargo van for a spin.

Also, I’d like the opportunity to apply for a job assembling electric cars as I fear my current career as a highly paid toyboy is only viable thanks to the JobKeeper payments.

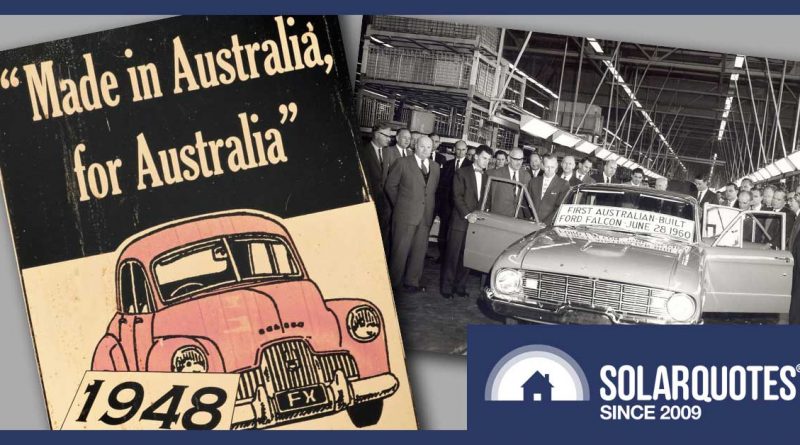

Australia had an automotive industry, but it died. It’s been three years since the last Australian car rolled off a production line. If electric vehicle (EV) production starts up, will it fare better?

In this post I’ll cover:

- The challenges Australian EV manufacturing faces.

- The advantages of manufacturing in Australia.

- Some bloody good reasons why the government should incentivise the shift from petrol and diesel vehicles to electric.

Manufacturing Hurdles Past And Present

A number of factors caused the Australian car industry to struggle in the past. The good news is some of the obstacles are no longer as obstacally as they were.

Drawbacks to building EVs here include:

- Australia suffering from the Dutch Disease

- Commodity based exports make our dollar volatile.

- High capital costs.

- High labour costs.

- The tyranny of distance.

The Dutch Disease: Australia has been described as a rich nation with a poor nation’s economy. Unlike most developed countries, rather than importing natural resources and paying for them with exported manufactured goods, Australia is a bizarro developed country and does it the other way around.

“Bizarro appearance in EV article feel shoehorned in!”

Economists call it “the Dutch disease“. Fortunately, it’s not as disgusting as most things we associate with the Dutch and doesn’t cause sufferers to wear wooden shoes or add superfluous mayonnaise to everything remotely edible.

It refers to how Australia’s large mineral and agricultural exports push up our dollar, making products produced overseas cheaper, driving local manufacturers out of business. This should decrease as our population grows and the economy diversifies. Also, the falling cost of renewable energy should cause two of our export commodities — coal and natural gas — to be much less important in the future. But maybe we’ll export energy in other ways.

The Dutch have wooden shoes in their blood. They literally have clogged arteries. (Image: Berkh)

A Volatile Dollar: Commodities1 such as iron ore, wheat, and natural gas have much larger price swings than manufactured goods. This volatility causes the Australian dollar to bounce up and down with commodity booms and busts.

While our kangaroo coin may jump around less in the future, between the pandemic, Brexit, and Americans voting for Bizarro Obama,2 at the moment, our dollar is looking pretty stable.

High Cost Of Capital: Because Australia is resource-rich with lots of opportunities for investment but a low population, we have trouble funding investment from our national savings. This made the cost of capital higher than in other developed countries. Our forced savings superannuation scheme — while wasteful and inefficient3 — helped, but after the Global Financial Crisis 13 years ago and now, with the pandemic related economic slowdown, money is cheap in all developed countries. There’s little difference between the Australian Reserve Bank’s interest rate of 0.25% and Spain’s 0%. Some countries — Japan, Denmark, and Switzerland — have negative interest rates.4

“Okay, Bizarro reference seems more relevant now.”

As interest rates are likely to stay low for a long time, as far as capital costs are concerned, Australia is pretty much as good a place to build electric cars as any other.

High Labour Costs: Australia’s labour costs are high compared to the world average. This is a good thing. We have a name for countries with low labour costs. They are called poor countries.

Considering there are more people in Australia receiving wages than paying them, you’d think media coverage on our high labour costs would be a little more upbeat. Still, oddly enough, we keep hearing people say high labour costs are a problem for the health of the economy rather than the entire freaking point of a healthy economy. But if you are one of those people who are worried about high wages you can relax, as we’ve been doing a good job of keeping them down lately:

Image: Business Insider Australia

Twenty years ago, high labour costs in a country would have been a serious problem for anyone wanting to manufacture cars. But now that capital — which is cheap — can more easily substitute for labour through automation and robotics, it’s no longer the problem it was.

The Tyranny Of Distance: While the world isn’t smaller than it used to be we have gotten a lot better at moving information, stuff, and ourselves around; so the tyranny of distance isn’t nearly as tyrannical as it used to be. These days it’s more like the mildly annoying inconvenience of distance.

Australian Advantages

Countering the cons, there are several pros to building EVs here:

- Stable government and institutions

- Existing automotive infrastructure and skills

- Decreasing electricity costs

- No federal incentives for electric vehicles

Government Stability: Compared to the rest of the world, Australia has a stable government. This may seem hard to believe as there are now teenagers who are confused by the fact we’ve had the same Prime Minister for two whole years. But when the main English speaking competition is ruled by loonies, we come out looking pretty good.

“Yeah, me get point. No need to rub it in.”

Businesses can invest in Australia and be confident the government would never act like a corrupt, tin-pot, kleptocracy and do something incredibly crooked5.

Or at least they can be confident they won’t try it more than once every three or four years.

Adelaide’s Got Talent — And Automotive Manufacturing Capacity: Adelaide used to be a major manufacturer of vehicles, and there is still plenty of automotive talent in the town who would leap at the chance to lend their expertise to building EVs. Plenty of businesses are still producing automotive parts for spares or export and would be happy to provide components.

No Incentives For Electric Vehicles: It may seem odd I’m marking this a plus, but zero incentives mean the only way to go is up.

4 Reasons For EV Incentives

The unfortunate fact is for Australian EV manufacture to happen any time soon, it will need some form of government incentive. Incentives can be direct or general in nature.

Direct incentives do assist the manufacturer but open a whole can of worms involving fairness, corruption, international trade agreements, and economic efficiency.

General incentives that apply to EVs overall are less problematic, but still need to be carefully designed to be cost-effective. Because they also apply to overseas EVs, they will help Australian EV manufacturing by increasing the market for their products rather than through a direct hand out.

Four good reasons why federal and state governments should provide general incentives to discourage internal combustion vehicles and promote the uptake of EVs:

- Death and sickness from vehicle pollution.

- Global warming.

- Energy security.

- Overcoming resistance to change.

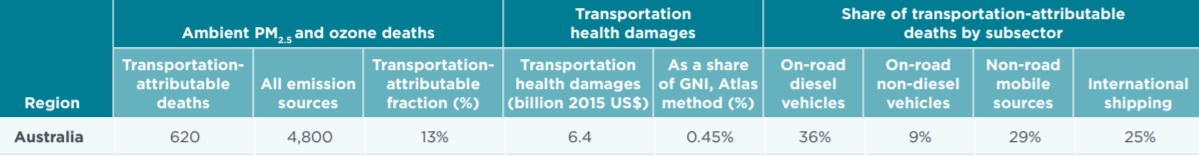

Australia’s Petrol & Diesel Death Toll: I went looking for information on how many deaths result from road transport pollution and found while plenty of people were happy to refer to thousands of deaths, they were less happy about providing actual references. I finally settled on using an international report that’s 5 years out of date because it reminded me of my beard. It looks impressive and is very thick.

The report estimated pollution from transport, in general, killed 620 Australians in 2015:

As the statistical value of a human life in Australia is now $4.9 million, just 620 deaths a year comes to over $3 billion a year. But if we dig into the details it gets a little more complicated, as this table shows:

It appears petrol and LPG powered cars were only responsible for perhaps 56 deaths in 2015. That’s far less than I expected, while the big killers are diesel vehicles, off-road vehicles used for agriculture and mining, and ships. Estimated deaths in 2015 for each category were:

- On-road diesel: 223 deaths

- On-road Petrol & LPG: 56 deaths

- Non-road vehicles: 180 deaths

- International shipping: 155 deaths

There should be incentives to shift to electric vehicles to reduce the death toll, and they should be particularly focused on diesel vehicles of all sorts. At the moment, around 26% of Australian road vehicles are diesel as are almost all non-road vehicles.

Global Warming: Australia used around one million barrels of oil a day last year. According to the National Emissions Inventory, transport as a whole was responsible for 100 million tonnes of CO2 emissions in 2019. However, this figure leaves out emissions from oil extraction, refining, and transport so, the actual emissions our transport is responsible for is at least 15% higher.

Due to Australia’s geographical position and large agricultural sector, we are particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. The national economic cost of climate change by 2030 has been estimated at over $500 billion.

While I don’t know how to work out the total cost of global warming from transport emissions, I can give a figure for cleaning it up. The bad news is removing over 100 million tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere each year is not going to be easy.

If we’re fortunate, the cost of removing one tonne of CO2 from the atmosphere and sequestering it may only be $70 per tonne if done on a large scale.6 This would make the cost of cleaning up Australia’s 2019 transport emissions $8 billion. For the average passenger car, it would be around $250 a year. Given the falling cost of electric vehicles, it’s going to be a lot easier to not burn that oil in the first place.

Energy Security: Conventional oil production in Australia may now equal 17% of our consumption. A couple of years ago it was about 13%. We also produce large amounts of natural gas condensate, which is a burnable liquid. But most oil and condensate production is exported overseas, and most fuel we use in our vehicles is imported. This reduces refining costs but makes us very vulnerable to disruptions in the supply of overseas oil products. Switching to EVs reduces this risk. Just how much benefit it will provide depends on how paranoid you are, but it’s certainly a consideration.

Resistance To Change: If we made conventional vehicles pay for the harm their oil-burning causes, my rough estimate is it would come to about 20 cents or more per litre of petrol and more for diesel. While we could make internal combustion vehicles pay for this at the petrol pump, politicians aren’t likely to approve, and it would place a hefty burden on low-income Australians.

But even if we made conventional cars pay this cost, it’s unlikely to result in a fast enough change to electric vehicles. This is because it runs into the problem of human psychology. While big companies that provide grid electricity are very sensitive to the bottom line, people buy cars based on habit, impulse, advertising, and how far their hairline has receded. While electric cars have low running costs, our natural monkey nature means we often fail to take this into account.

As an example of resistance to change, I told a six-foot-three biker who abuses so many steroids he looks like a vaguely humanoid pile of shrink-wrapped bunya nuts that he should buy an electric motorcycle. He looked at me with terror in his eyes and told me he was scared of what other bikers would say if his bike didn’t go “VROOM”. I told him he could make “vroom” noises with his mouth, but he wasn’t convinced.

On the bright side, in August Australia’s best selling car was the Toyota RAV 4 hybrid SUV. While this may be a blip, it does show Australians aren’t wedded to conventional vehicles.

Because we need to kick our oil habit quickly, we can’t rely on human rationality to save the day and have to provide additional incentive to act as a kick in the pants. Over a dozen countries are doing this by banning the sale of conventional cars by 2050 with Norway’s ban staring in 2025. Australia doesn’t have to go this far, but we should do something.

An EV Incentive Already Exists

Electric vehicles already receive an indirect incentive because they avoid the fuel excise that pays for roads as well as contributes to general revenue. This will need to change in the future as EVs take over, but if you are worried about it now when they’re around 0.2% of cars in the country – you are being a dick. It’s fine to make a plan for the future, but it’s foolish to make EVs pay for the cost of using roads while conventional cars don’t pay for the cost of killing us.

A Modest Proposal For EV Incentives

It is possible to create EV incentives that don’t place a burden on lower-income Australians and cost the government zero additional dollars.

I’d suggest something along the lines of:

- A subsidy for electric cars based on their reduced environmental and health costs.

- This subsidy is paid for with an increase in the purchase price of internal combustion engine vehicles. The most fuel-efficient have no increase, medium fuel efficiency vehicles have a modest increase, and the least fuel-efficient have a hefty price increase.

- A commitment to introduce strict fuel-efficiency measures in 10 years time so vehicle manufacturers will know they have to change and can’t expect to dump outdated internal combustion engine cars in the Australian market.

Australian EV Manufacturing — Fingers Crossed

There are pros and cons to building EVs in Australia, but — in my not at all professional opinion — I’d say they more or less cancel out and Australia is likely to be as good a place to build them as anywhere else. Hopefully, we will see manufacturing happen in Adelaide, but sadly it probably depends on whether or not politicians decide to provide any incentives.

Footnotes

- Something is a commodity if a kilogram of it is much the same as any other kilogram. A tonne of Australian Standard Noodle Wheat is much the same as any tonne of Standard Noodle Wheat, and China doesn’t care if it comes from Australia, the US, or Ukraine. (Actually, they prefer a mix so they won’t get too hungry if they piss one off.) ↩

- Trump won the Presidency with 48% of the US popular vote. Because of the way their Electoral College works, Biden will have to get 53% or more of the popular vote to have over a 50% chance of winning. The Electoral College is like democracy, but smaller. ↩

- With a slightly less moronic approach, every Australian would now be, on average, $25,000 better off. And that’s just by being less moronic — we would be even better off if we were smart. ↩

- There are a few reasons why money is so cheap right now, but I think it mainly boils down to rich cowards. There are too many rich people with too much money who are too scared to invest it in anything that carries any real risk. The standard cures for this are inflation, wealth taxes, and death duties, so we may see more of them in the future. ↩

- like attempt to funnel hundreds of million dollars to local media organisations in expectation of their support in the next election ↩

- Various methods have been suggested, including burying charcoal, dumping plant matter in deep ocean waters, and grinding up rocks so they’ll help remove CO2 from the atmosphere. ↩

Original Source: https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/build-electric-cars-australia/