Australian Submarines May Go Nuclear But Our Power Stations Never Will

Australia recently decided to buy nuclear-powered submarines as part of the AUKUS pact with the UK and United States.

Assuming it goes ahead, the first sub may be ready around 2040. But while our submarines may have nuclear reactors, our power stations never will.

There is a simple reason Australia will never have nuclear power despite deciding to get reactors that wander around under the ocean. The reason is…

- Nuclear power is too expensive for Australia.

Every other concern — whether it’s safety, waste disposal, decommissioning, insurance, or location — is irrelevant because nuclear energy can’t clear the first and vital hurdle of making economic sense.

Some suggest building nuclear power in addition to renewables because the threat from global roasting is so great we should fight emissions using every means at our disposal. But this would be counterproductive because:

- Nuclear power consumes resources that would result in greater emission cuts if used for solar and wind generation plus energy storage.

In other words, $1 spent on solar power will cut greenhouse gas emissions far more than $1 spent on nuclear energy.

Finally, some people say we need nuclear power to provide a steady source of low emission baseload generation, but this suggestion is completely nuts. Even if we built nuclear power stations, they would soon be driven out of the market in the same way coal power is because:

- Nuclear power has exactly the wrong characteristics to be useful in a grid with a high penetration of solar and wind.

Australia currently doesn’t have a nuclear power industry, and building submarines with American made sealed reactors that are never refuelled will do next to nothing to make nuclear power more cost-effective.

In this article, I’ll explain why nuclear power makes no economic sense in Australia, and at the end, I’ll also whinge a bit about nuclear submarines.

You may think I have zero qualifications to have an opinion on submarines, but I say being half-Dutch automatically qualifies me to talk about everything below sea level. Or, to be precise, half the things below sea level.

But if you don’t find that convincing and want a neutral viewpoint, you can read what a Finnish blogger has written about the AUKUS pact. As a Finn, I don’t think he understands some of the subtleties of our culture, and that’s why he thought a good name for a post on our Navy would be “A Pounding in the Pacific“.

[embedded content]

I’m Not Saying Anything About Existing Nuclear

To be clear, I’m only saying Australia will never get nuclear power. I’m not saying a damn about whether or not existing nuclear reactors should be shut down. If you happen to own a working nuclear power station in another country, you have my permission to keep it running as long as you like. If you live in Bulgaria, I’ll even send you a free roll of duct tape.

Nuclear Power Is Ridiculously Expensive

The cost of energy from new nuclear isn’t just expensive; it’s ridiculously expensive. Here are examples of reactors under construction in developed countries, using Australian dollars at today’s exchange rate:

- Finland’s Olkiluoto #3 reactor: So far, this 1.6 Gigawatt reactor has cost about $14 billion, which is around $8,750 per kilowatt of power output. Construction started in 2005 and was scheduled to be completed in 2009. Due to delays, it’s now scheduled to commence normal operation in February 2022 for a total construction time of 17 years.

- France’s Flammanville #3 reactor: The cost of this 1.6 gigawatt reactor is approximately $31 billion. That’s $19,400 per kilowatt. Normal operation is scheduled for 2023 — 16 years after construction began.

- UK’s Hinkley Point C: These two reactors will provide 3.2 gigawatts of power and cost around $42 billion. That’s $13,100 per kilowatt. Construction began in 2018, and they’re currently scheduled to come online in 2026.

- US Vogtle 3 & 4: These two reactors in Georgia (the US state, not where Stalin was born) will total 3.2 gigawatts and, by the time they are complete, may cost over $38 billion. That’s around $12,000 per kilowatt. Construction started in 2013, and they’re expected to come online next year. These are the only commercial reactors being built in the United States.

As you can see, new nuclear isn’t cheap. Note these aren’t the most expensive reactors under construction in Western Europe and North America, they’re the only ones under construction.

If you think these reactors are expensive to build but provide cheap electricity, that’s not the case. The Hinkley Point C reactors under construction will receive a minimum of 21 cents per kilowatt-hour they supply for 35 years after they come online. If the wholesale electricity price goes above 21 cents, they’ll receive that instead. The 21 cents is indexed to inflation, so it will remain ridiculously expensive for the full 35 years.

In the US, households in Georgia will have paid around $1,200 each towards the new Vogtle reactors by the time they come online. After that, their electricity bills will increase by around 10% to pay for the new nuclear electricity. For another nuclear power station to be constructed in the US would require a payment per kilowatt-hour similar to or higher than Hinkley Point C.

Australia doesn’t have any pixie dust it can sprinkle on reactors to make them cheaper than in other developed countries. Because we don’t have an existing nuclear power industry, they’re likely to cost us more. One option to get a lower price would be to ask China to give us a good deal on a reactor as part of their Belt and Road initiative, but they’ve shown no interest in giving anyone else a good deal, so I doubt that will work. If Australia does decide to go ahead with nuclear power, Chinese engineering is likely to be the least expensive option.

Nuclear Energy Is Many Times Too Expensive

Here are the average market prices, per kilowatt-hour, for wholesale electricity in the eastern states last financial year:

- NSW 6.5 cents

- QLD 6.2 cents

- SA 4.5 cents

- TAS 4.4 cents

- VIC 4.6 cents

Even in the most expensive state — NSW at 6.6 cents per kilowatt-hour — Hinkley Point C’s minimum price is over three times as much.

Last year, wholesale prices were affected by the pandemic, so they are from the financial year ending in 2019. A period when wholesale electricity prices were exceptionally high:

- NSW 8.9 cents

- QLD 8.0 cents

- SA 11.0 cents

- TAS 9.0 cents

- VIC 11.0 cents

Even in the most expensive states during a period of high prices, wholesale electricity prices were still half the minimum cost of electricity from new reactors underway in the UK.

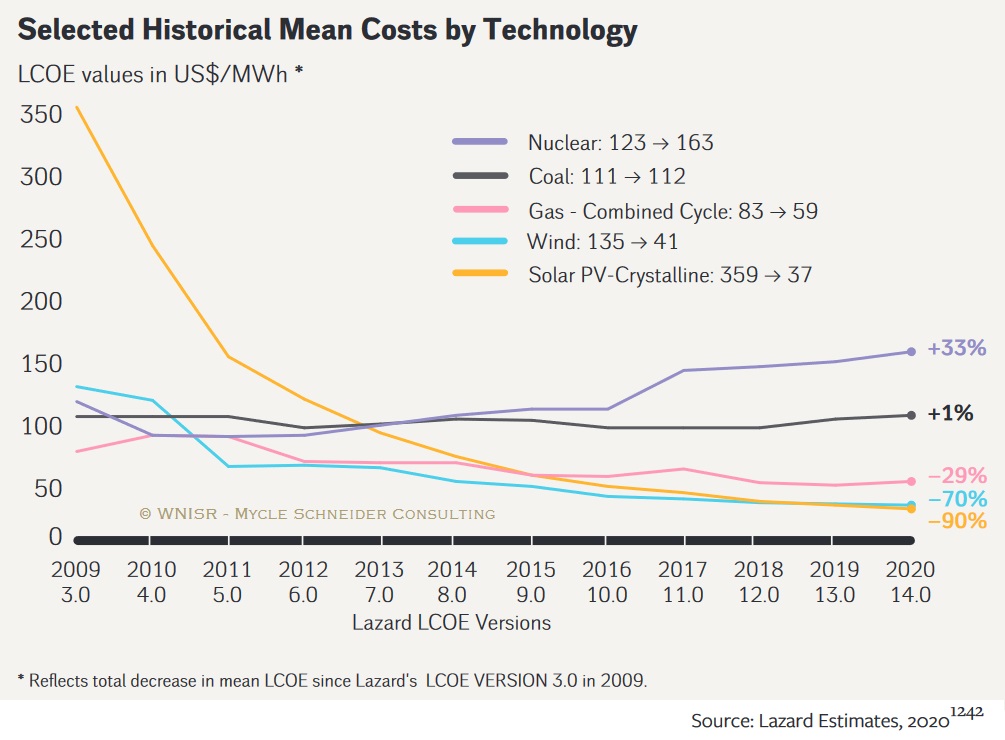

This graph for the US from page 293 of The World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2021 clearly shows why we will never build purple nuclear in Australia, which has plenty of sunny orange and blowy blue.

Nuclear Can Get Cheaper But Won’t Get Cheap Enough

New nuclear power is so expensive it makes a great idiot test. For anyone who seriously suggests Australia should build nuclear power capacity the options are:

- They haven’t done basic research.

- They’re deliberately deceptive.

- They’re delusional.

Whatever the reason, it’s clear evidence they can’t be trusted and should never be in charge of anyone else’s money.

But nuclear energy can get cheaper. If enough money is spent improving designs and a sufficient number of new reactors are built, I’m sure the cost of new nuclear power in Western Europe and the US could be cut by more than half. But that won’t be cheap enough.

The first full-scale nuclear power station came into operation in the UK in 1956. Over the 66 years since then, nuclear power received a lot of investment but failed to become competitive with coal generation. We don’t even have to look at costs to know this, it’s obvious from the amount of coal we export to countries with mature nuclear industries.

I’m glad places like France decided to use nuclear energy rather than coal, but if it can’t get cheaper than coal, we will never build nuclear capacity in Australia. This is because solar and wind generation plus energy storage is cheaper than new coal and is gradually driving existing coal power stations out of the market. If nuclear energy can’t beat coal after 66 years of development, it’s not about to suddenly beat cheaper alternatives.

Small Modular Reactors Are More Expensive

An SMR is a Small Modular Reactor. There have been claims these will provide cheap energy in the future, but this seems unlikely given their designers have stated that…

- Before cost overruns are considered, SMRs will produce electricity at a higher cost than current nuclear reactor designs.

Being more expensive than conventional nuclear power is a major obstacle for any plan to supply energy at a lower cost.

The advantage of SMRs is they are supposed to be less likely to suffer from disastrous cost overruns. This means they are a more expensive version of a type of generation that is already too expensive for Australia before cost overruns. While any cost overruns that do occur may not be as bad as conventional nuclear, that’s not what I call a good deal.

There is nothing new about small nuclear reactors. India has over a dozen reactors of 220 megawatts or less in operation. But all Indian reactors now under construction are larger because they want to reduce costs. Technically their small reactors aren’t modular because major components weren’t constructed at one site and then moved to where they were used. This leads to another major problem with SMRs…

- They don’t exist.

Before Australia can deploy an SMR, a suitable prototype reactor will have to be successfully built and operated. Then a commercial version will need to be developed and multiple units constructed overseas without serious cost overruns and used long enough to show they can be operated safely and cheaply.

Given nuclear’s prolonged development cycle, this could easily take over 20 years. The very best estimate for the cost of electricity from an SMR I have seen is around 6.2 cents per kilowatt-hour and it relies on everything going perfectly — a rare thing for nuclear power. It also leaves out several costs that have to be paid in the real world.

It’s a fantasy figure for vapourware that doesn’t yet exist, and only someone suffering an attack of the vapours would regard it as a solid figure. But if it somehow turns out to be correct, it’s still more expensive than wholesale electricity in most Australian states over the past year, and I’m certain it will be much too expensive in 20+ years.

If I’m Wrong, Buy Nuclear When I’m Wrong

Let’s say I’m completely wrong, and in the future, other countries build reactors that provide energy — when all costs are included — for less than renewables plus energy storage. This will never happen. I’ve made mistakes in the past, but I’ve only ever made mistakes this large when getting married.

But let’s pretend it happens. In this case, we should build nuclear when it’s cheaper than other alternatives — not before. If nuclear energy becomes cheaper in the future, it won’t make your old expensive reactor refund the difference. Building nuclear before it’s cheaper than other low emission options would be what economists call freaking stupid.

Poor Choice For Emission Reductions

Some people ask…

“Why not build both nuclear and renewable capacity to reduce CO2 emissions as rapidly as possible?”

The answer is…

“Because every dollar invested in nuclear will cut emissions by much less than a dollar spent on renewables.”

If the goal is to cut emissions rapidly, it’s counterproductive to invest in nuclear. Australia doesn’t have existing nuclear capacity or a half-built reactor, so whether it makes sense to keep old reactors operating or complete construction doesn’t come into it.

Nuclear capacity isn’t quick to build. Some notable examples:

The first two are pretty extreme, but the last one takes the yellowcake. But if you don’t count the 22 year break they took, only 21 years were spent actually building it.

Looking at South Korea, a country better than most at finishing nuclear projects on time, out of 30 reactors, their shortest construction time was four years. All others took five or more years, with the longest taking 10 years.

Because Australia has no nuclear power industry, it would take more than five years to build a nuclear power station even if we could start construction today1. But Australia can increase its solar energy generation almost immediately. Extra wind power will take months to arrange, as wind turbine purchases are more complex than just ordering extra solar panels and inverters. Firming the grid with energy storage is also fast. The world’s largest battery, the Hornsdale Power Reserve or “Tesla Big Battery”, was built in 100 days.

Whether cost or time are considered, nuclear energy is a poor choice for reducing emissions.

Nuclear Energy Not Needed For Baseload Generation

One of the craziest reasons given for building nuclear power in Australia is we need low emission baseload generators. This idea is nuttier than a lumpy chocolate bar because:

- No baseload generators are required.

- Like coal, nuclear power has the wrong characteristics to support a grid with high solar and wind generation.

It’s impossible to argue that we need baseload generators that run continuously (except for maintenance). This is because South Australia has none. The state doesn’t continuously import electricity either.

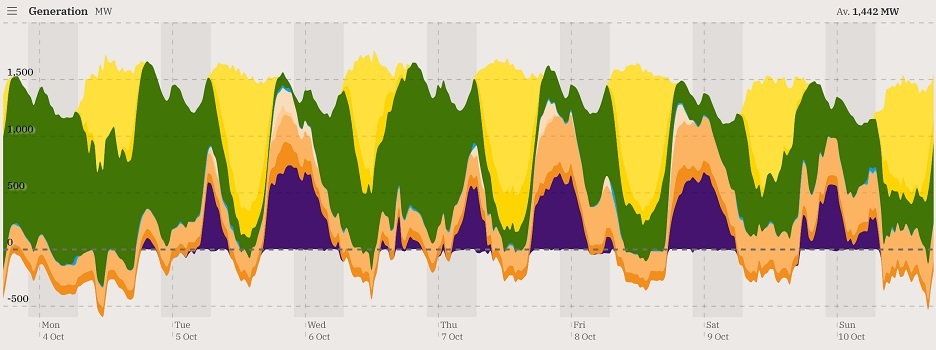

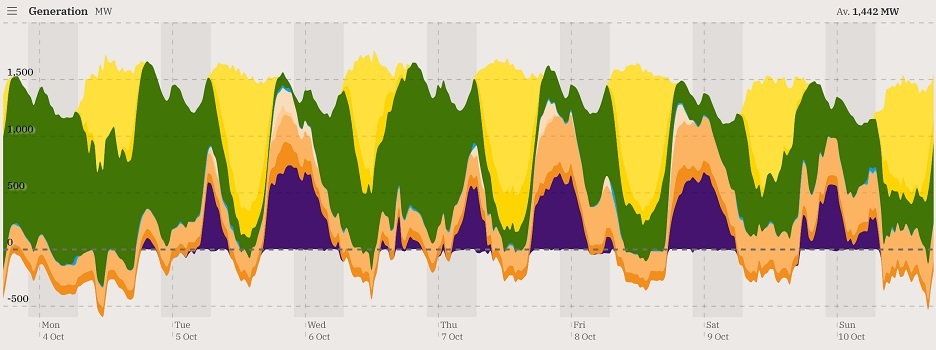

This graph shows South Australian electricity generation over a week. It both importing (purple) and exports (below the dotted line). Over this time, 72.4% of electricity consumption was renewable energy generated from solar power (yellow) and wind (green). The orange is gas generation. Note how solar and wind often supply more than the state’s total electricity consumption. (Image: OpenNEM)

Despite having no baseload generators, SA still manages to meet demand as well as other states.

South Australia had coal baseload generators in the past, but as wind and solar power capacity expanded, there were increasing periods of low or zero wholesale electricity prices2 resulting from solar and wind having zero fuel costs. Because their fuel is free, they have little or no incentive not to provide electricity even if they receive next to nothing for it.

Because coal power is expensive to start and stop and saves very little money by shutting down because its fuel cost is low — but not zero — it often had no choice other than to keep operating during periods when it was losing money on every kilowatt-hour generated.

In 2016 South Australia shut down its last remaining coal power station because it was no longer profitable. This same process is happening throughout Australia as solar, wind, and energy storage capacity increases. In a (hopefully) short period of time, renewables will drive coal power out of the market.

If it doesn’t make economic sense to keep existing coal power stations around to supply baseload power, it definitely makes no sense to replace them with more expensive nuclear reactors with the same problem – that shutting down saves little money because their fuel cost is low. Building a nuclear power station and then only using it half its potential capacity almost doubles the cost of energy it produces.

Using nuclear to firm renewables supercharges its lousy economics.

Batteries Also Make Nuclear Uneconomic

As solar and wind generation increases, the worse the economics of nuclear energy become. This is because its low cost pushes down wholesale electricity prices. There can be periods of high electricity prices when renewable output isn’t sufficient to meet demand, but this isn’t enough to make nuclear pay. Nuclear wouldn’t pay if there were no such thing as battery storage, but battery storage makes its economics worse.

Next year a 580 megawatt-hour battery will be built in Victoria for $270 to $300 million. That’s around $500 per kilowatt-hour. If each kilowatt-hour of storage capacity provides a total of 4,000 kilowatt-hours of stored energy over its lifetime — a not unreasonable amount — then the cost of storage will be around 13 cents per kilowatt-hour.

That’s not cheap, but still a lot cheaper than nuclear energy, especially since we will often charge it with renewable electricity that costs 1 cent or less per kilowatt-hour. It also has the advantage it will supply electricity when prices are high, rather than more or less continuously, as is usually the case for nuclear power.

There’s no reason to expect the cost of utility-scale battery storage to stop falling anytime soon, so by the time a nuclear power station could be completed in Australia, its economics will be far worse from falling energy storage costs alone.

Other Nuclear Energy Issues

There are many issues associated with nuclear power that are often discussed but are irrelevant. I’ll quickly mention and dismiss half a dozen or so:

Safety: For a while, I lived 40 km from a nuclear power station that suffered a criticality event while I was there — a major safety breach. At the time, it didn’t worry me in the slightest. This is because they successfully covered it up for eight years.

Despite being endangered by dishonest nuclear management, I’d have no problem living next to a new nuclear reactor today. I’m confident they’re very safe. But anyone who tells you they’re completely safe has a raisin in their braincase.

Nuclear power stations are complex systems, and we can’t be 100% certain what may go wrong or what deliberate sabotage could achieve. But it doesn’t matter how safe or unsafe they are. It’s irrelevant because nuclear power is too expensive.

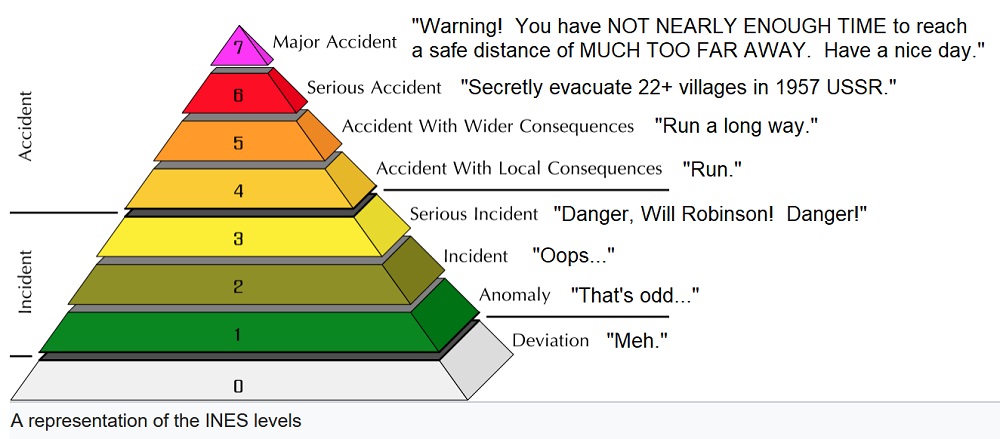

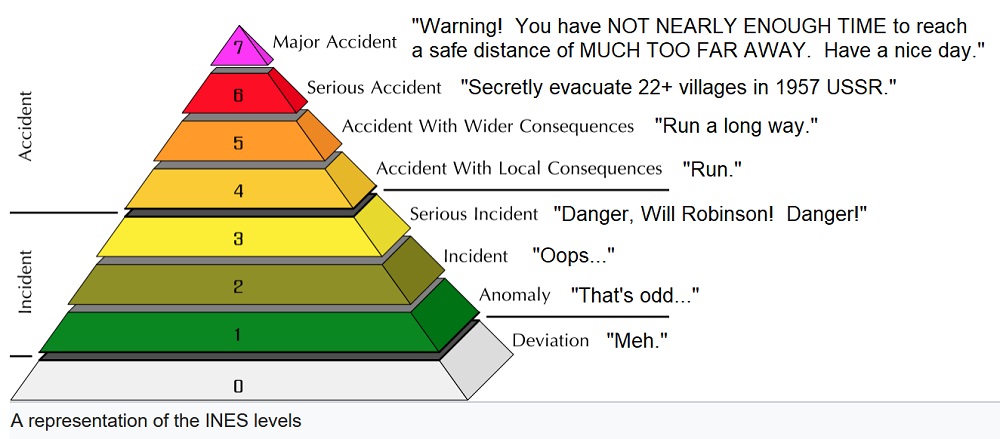

The International Nuclear Event Scale and my own interpretation of the different levels of danger. The cover-up that occurred 40 km from me was only level 2, but a culture of cover-ups and inaction may have led to a far worse disaster.

Nuclear Waste: Nuclear waste can be stored in a way that makes it extremely unlikely to ever harm anyone — provided you spend around $5.5 billion doing it. While (hopefully) safe disposal only comes to a fraction of a cent per kilowatt-hour generated, it’s still a hell of a lot more than dealing with old solar panels that can potentially be 100% recycled. But nuclear waste disposal is irrelevant because nuclear power is too expensive.

Nuclear Proliferation: Nuclear fuel from normal reactors is very difficult to make into atomic bombs. But this is irrelevant because nuclear power is too expensive.

Insurance: Nuclear power can’t be fully privately insured because no company can cover the cost of a major nuclear accident. Governments can set insurance premiums at a reasonable level, but this is irrelevant because nuclear power is too expensive.

Nuclear Fuel Reprocessing: France reprocesses its nuclear fuel. This reduces their need for uranium by 17%. Given the current low cost of uranium, reprocessing nuclear fuel makes no sense. It’s also irrelevant because nuclear power is too expensive.

Thorium: Using thorium instead of uranium could reduce the cost of nuclear fuel. But uranium is only a tiny portion of the total cost of nuclear energy, so it will make little difference. Because it makes little difference, it’s irrelevant because nuclear power is too expensive.

Decommissioning: Nuclear power is very expensive to build and decommission at the end of its life. This is why the nuclear energy industry likes to push these costs onto the public while hanging around for the profitable part in the middle. But the high cost of decommissioning is irrelevant because nuclear is too expensive.

A Submarine Whinge

I can think of several things likely to provide Australians with better protection than nuclear-powered submarines. These include:

- Creating a lab that can produce mRNA vaccines that can help fight the current pandemic and the next.

- Cutting greenhouse gas emissions to build better relations with other nations and reduce the potential for conflict from climate change.

- Introducing vehicle fuel efficiency standards or simply promoting electric cars will reduce oil imports and improve energy security.

- Raising superannuation contributions would increase investment and allow us to spend more on defence in the future if required.

- A wealth tax that reduces consumption and shifts more resources into investment would also improve our capacity to protect ourselves in the future.

Australia is in the very fortunate position of not having any enemies3, despite our PM’s habit of leaping into his own mouth feet first. Our geographical position also means there is no nation with both the will and means to invade Australia.

This is why I don’t see a need for nuclear submarines. I don’t even see why we need conventional ones. But if you put a loaded torpedo to my head and forced me to say what I considered the least-worst way for the Australian Navy to acquire submarines, I would say buy non-nuclear ones made overseas, but build an uncrewed supply submarine here.

Nuclear Power — A Complete No Go For Australia

There’s a good chance Australia will never have nuclear submarines. The first won’t be completed until around 2040 and we can’t even be certain the United States will still be around in four years. The next person in the Oval Office could be President-for-life of the Freedom States of America.

But assuming we do get nuclear submarines, they will have reactors made and fueled in America. We will have a small number of people trained in the operation and maintenance of a naval reactor that is nothing like a nuclear power station. This is around 18 years away and will do bugger all to lower the cost of nuclear power in this country.

Footnotes

- Not even using the work already done at Jervis Bay will speed things up. ↩

- There were also long periods of negative electricity prices, but these will mostly disappear as the value of LGCs (Large-scale Generation Certificates) decrease and battery storage increases. ↩

- If you think having a trade dispute makes a nation your enemy, remind me to never attend any garage sale you have. ↩

Original Source: https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/submarines-nuclear-not-power-stations/