COP26: Australia Stupid Not To Join Global Methane Pledge

Last week at the COP26 in Glasgow, more than 100 nations took the Global Methane Pledge and committed to reducing emissions of this dangerous greenhouse gas 30% by 2030. It was a shining moment in history as the world’s people came together to act for the common good.

When I say “the people of the world”, I actually don’t mean all of them. For a start, there wouldn’t be enough room. There are a few countries not taking part. Among them are China, India, Iran, and Russia. Australia is also one of them.

Under other circumstances, it might be nice to cosy up with a few major trading partners like this, but this is not a group it’s in our interest to join. India and Iran are poor nations, so I’m not going to pick on them for letting the opportunity pass by, but both China and Russia are solidly middle income and can afford to make the effort.

Most shamefully of all, Australians are five times richer on a per capita basis, and if any nation among the abstainers can afford to reduce methane emissions, we’re it.

We weren’t only faced with a clear moral choice. We also had to decide between acting sensibly and helping secure humanity’s future or acting stupidly and unnecessarily, putting it at greater risk.

Our leadership chose to be stupid.

Australia should have taken the pledge because it would be relatively easy for us to cut methane emissions 30% over the next eight years. Even from a completely venal point of view, we were idiots for not taking the easy win.

What The Hell Is Methane?

Methane is a colourless, flammable gas. It’s the main component of natural gas that we burn to generate electricity and provide heat for homes and industry. It’s produced naturally by methanogenic microorganisms found in rotting vegetation, soil, and the digestive tracts of animals such as cows, sheep, and termites.

It’s an odourless gas. This may surprise those who think it’s a major component of flatulence, but humans are minor producers of digestive methane. Although there are exceptions.

Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas and behind a hefty chunk of global warming. Methane emissions from civilization are roughly responsible for 16% of global warming that has occurred over the past few hundred years. But the calculations involved in working that out are really complex, and climatologists can get very cranky with idiots who try to guesstimate it down to a simple percentage.

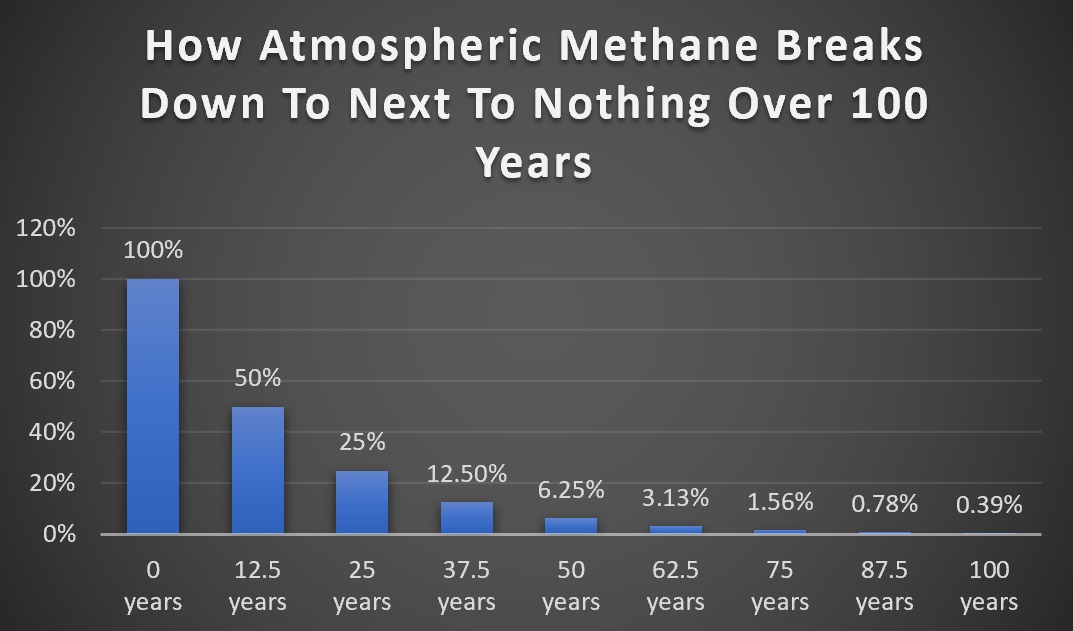

Measured over 100 years, one tonne of methane emissions will result in around 34 times as much warming as one tonne of CO2 emissions1. Unlike CO2 — where much of what we’ve added to the atmosphere will still be there after thousands of years unless we do something about it — methane breaks down over time. After 50 years, most of what’s in the atmosphere now will be gone.

The half-life of atmospheric methane is around 12.4 years, but this can vary considerably for reasons we only partially understand. The graph below shows how methane breaks down over time:

This graph assumes a methane half-life in the atmosphere of 12.5 years rather than 12.4. This is partly because the value is approximate but mostly because a round 100 years looks better than janky 99.2 years.

Because methane emitted today will be half gone after around 12 to 13 years, its warming effect is front-loaded. While over 100 years its warming effect will be around 33 times greater than CO2, over 20 years its warming effect is around 80 times higher.

But that’s only considering the direct warming effects of methane. Unfortunately, it also interacts with aerosols in a way that increases its warming effect over 20 years to an estimated 104 times higher than CO2.

Because methane is a powerful greenhouse gas but also breaks down over time, cutting emissions now can significantly slow global warming over the next few decades. This means the Global Methane Pledge makes a lot of sense.

But before anyone gets too excited, I should mention when methane breaks down, it converts into CO2. While CO2’s greenhouse effect is much less powerful, it does mean all the warming from methane emissions won’t disappear if we wait 50+ years.

Natural Methane Emissions Not Counted

Around 40% of methane emissions are from natural sources such as wetlands and termites. These sources are not included in the Global Methane Pledge, which only covers emissions from human activity.

In Australia, emissions from cows and sheep are considered part of human activity, as our beef and wool industries weren’t created by mother nature. You might expect methane directly produced by humans would count as part of human activity but — interestingly enough — human farts are considered natural.

Australians only fart out around 3,000 tonnes of methane a year, which is under 3% of emissions from our other activities. I’m not saying it’s okay to fart as much as you want, but if you let one rip, it won’t interfere with any international agreements, provided it’s below the level of a nuclear weapons test.

Australia’s Methane Emission Levels

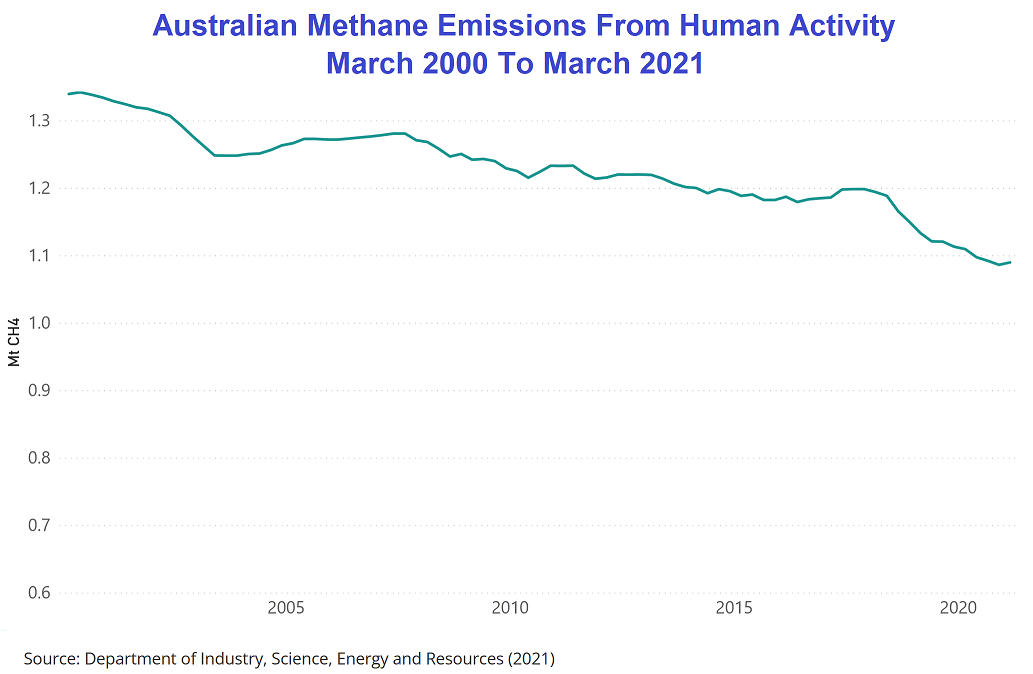

Here’s a graph of Australia’s methane emissions from human activity this century:

Graph taken from National Greenhouse Gas Inventory report, but I added the blue title.

As you can see, it has already been trending down, and if the rate continues, emissions will be 7% lower by 2030.

In 2020 methane emissions were 1.09 million tonnes2. If we’d joined the Pledge, our emissions would need to be 760,000 tonnes by 2030.

Australia’s population is now 25.9 million, with an average household size of 2.6 people. This means our current emissions average out to…

- 42 kg of methane emissions per person

- 110 kg of methane emissions per household

While around 110 kg per family may not sound too bad, if burned in a 50% efficient combined cycle gas power station, it would generate around 820 kilowatt-hours. So the methane our activity releases into the atmosphere is enough to generate the grid electricity consumption of Australian homes for around two months of the year.

Methane Emissions By Sector

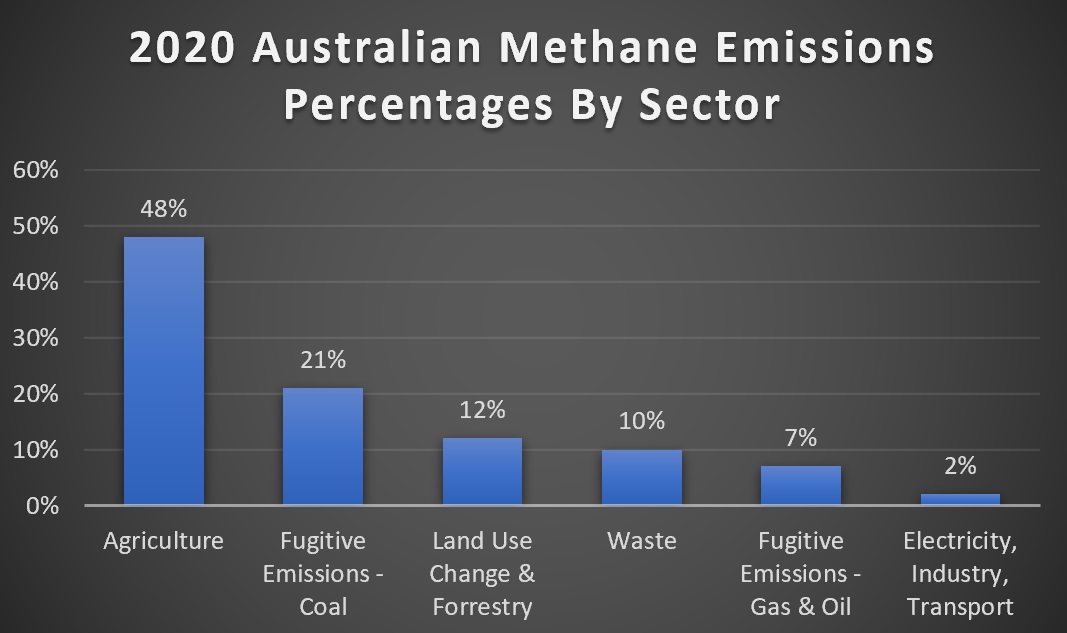

Here’s a graph showing Australia’s methane emissions for 2020 by sector:

These figures are from the Australian Greenhouse Gas Inventory. There is some dispute over how accurate they are, but I’ll assume they’re close enough for the back of the envelope estimates I make in this article.

Note to politicians: “Back of the envelope” refers to simplified calculations. It does not mean deciding calculations are correct because they’re written on the back of an envelope stuffed full of cash.

Here’s a quick rundown of the emission sources:

Agriculture: Methane is released by methanogenic microorganisms in farm soils, the burning of agricultural wastes, and the use of nitrogen fertilizer. But over three quarters comes from cows and sheep farting, burping, and pooping.

Fugitive Coal Emissions: Fugitive emissions are accidental or unintentional emissions from industry. Those from coal mining are the second-largest source of Australian methane emissions. Most come from coal releasing methane after it has been dug up and crushed. This process creates heat and is one of the dangers of coal mining, as it can result in spontaneous combustion if care isn’t taken. (That’s spontaneous combustion of coal — not people in the area.)

Land Use: When land is cleared, the soil can release methane. The burning of vegetation also releases it. Anything that makes ground marshy or swampy can cause methane emissions from biomass rotting in a low oxygen environment.

Waste: This mostly comes from landfill. When our rubbish rots, microorganisms release methane.

Fugitive Emissions — Gas & Oil: It’s unclear how much emissions result from Australia’s coal seam gas extraction, but these figures put the total for gas and oil extraction at one-third of coal.

Electricity, Industry, and Transport: It may seem surprising that these large parts of the economy are only responsible for 2% of emissions, but there’s a simple reason. Unlike other sectors, they have to pay good money to be supplied with natural gas and have an incentive not to let it go to waste.

It’s Easy To Cut Coal & Gas Fugitive Emissions

Coal mining is responsible for around 21% of our methane emissions, so all Australia needs to do to meet the Global Methane Pledge is end coal mining over the next eight years, plus reduce emissions in other areas by 11.4% and we’re done. That’s a 30% reduction.

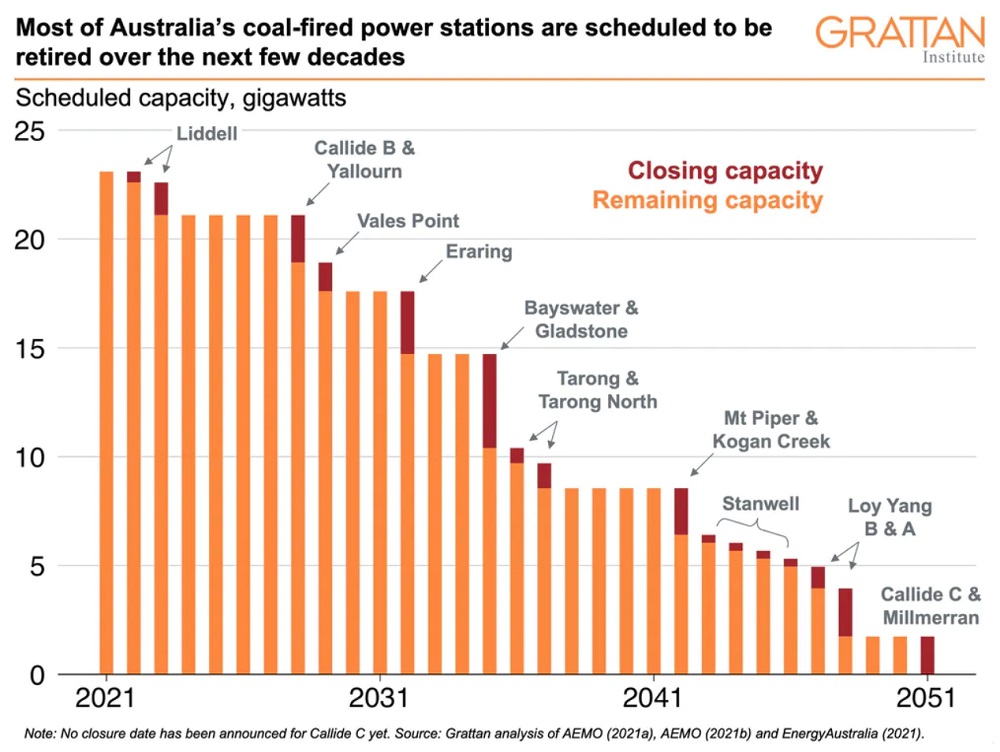

But I don’t think our Federal Government would consider that a good idea. While I think we should end domestic coal fired power generation over the next five years3 — with possible exceptions for seasonal or emergency use — officially our government doesn’t want to do that until 2051.

This graph was put together by the Grattan Institute and shows times given for Australian coal power station closures. According to this, we won’t be rid of coal power until 2051. (Note that, even though I’m aware this graph has been floating around the internet for a while, I am far too lazy to check if it needs to be updated.)

Fortunately, the actual chances of coal power lasting that long are around those of a snowball in hell — or most places on earth at the moment.

Instead of recognizing the world needs to rapidly phase out coal, our current leadership prefers to pretend demand for domestic and exported coal will be as strong in 2030 as it is now, and that’s not going to happen.

Low-cost renewables are killing coal generation in Australia, and our export markets have shown they are quite capable of investing in solar energy and wind power generation. Singapore, which is kind of crowded, is getting the Northern Territory to toss an extension cord across the Tasman Sea fence to Indonesia and then across the Java Sea so they can enjoy Australian solar power.

Metallurgical coal exports are also set to decline. This is used for steel making and, by tonnage, was 47% of Australia’s coal exports last financial year. Some decline may occur from increased steel production methods that don’t require coal, but the main fall is likely to come from reduced steel use in China.

There’s nothing unexpected about falling Chinese steel consumption at this point. Countries use a lot as they industrialise but then ease off and rely more on scrap metal. While other large countries such as India, Indonesia, and Nigeria could increase their demand, it may not compensate. Eventually, those countries will also reach a point where demand decreases.

Demand for natural gas will also fall. It will still be used to firm grids in 2030, but demand will decrease as renewable energy generation increases. In addition, affordable battery storage will cut gas generation in the evening. Australia has built the world’s biggest battery near Geelong because it’s cheaper than constructing extra gas generation — and this is where a lot of the gas consumed in Asia comes from. Other countries that have to pay the extra expense of importation will soon follow suit.

We Can Cut Agricultural Emissions

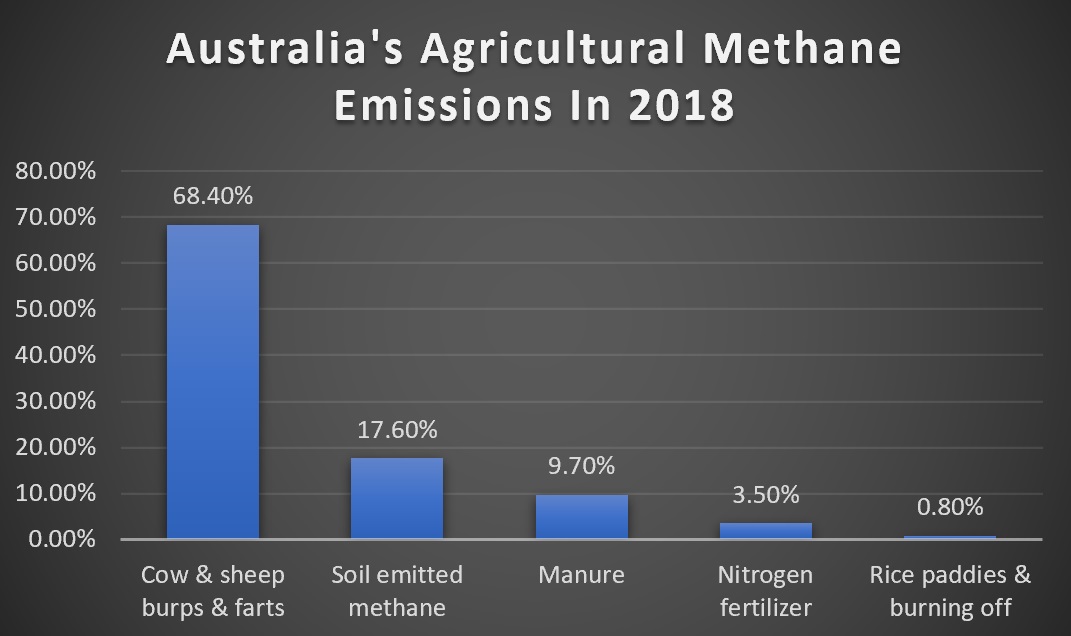

Almost half of Australia’s methane emissions are from agriculture. Here’s a graph showing where they came from in 2018:

Information ripped from this WA Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development page.

Over two-thirds of agricultural methane emissions in 2018 came directly from ruminants — animals with four stomach compartments. These are cows, sheep, and goats. (Also giraffes, but farming them never took off here because making the fences high enough is hard work.)

I’m optimistic we can reduce these animal emissions because their methane production results from inefficient digestion. Making it more efficient will reduce emissions and feed requirements, improving the bottom line for farmers. So reducing ruminant methane emissions will be win-win rather than only rear wind.

Some promising methods of reducing livestock methane emissions are:

- Breeding: Animals with the right genetics produce less methane.

- Feed additives: A daily handful of red algae seaweed fed to feedlot cattle can nearly eliminate their methane emissions. This is useful because beef cattle spend around 12% of their 18 month existence in feedlots and produce more methane per day there than in the paddock.

- Increased meat production from non-ruminants such as pigs, poultry, kangaroos, and fish (Admittedly, cattle do better than fish on the plains out of Narrabri.)4.

We can also reduce other sources of emissions. Changing land management practices can decrease emissions from soils, and if feedlots and piggeries get their shit together, they can burn the methane it releases. We could use it to generate electricity on-site or sold, as is done with biogas in Europe. But note the value of natural gas (methane) is likely to fall, so there may not be a strong demand for it in the future.

Thanks to its fondness for consuming manure, this annoying thing has done more to reduce methane emissions than our entire Federal Government. Not only does it beat them on environmental issues, it’s beating them in their primary area of expertise. (Image: Wikipedia)

Nitrogen fertilizer can increase emissions because it feeds methane-producing microorganisms in the soil and the water systems it enters. Because farmers don’t like to waste money by adding more nitrogen to crops than is necessary, improved management has the potential to benefit farmers and the environment.

Waste Emissions

Around 10% of Australia’s methane emissions are from waste, and most of it comes from landfills. Australia already has projects to capture landfill methane and either burn it off or use it for electricity generation. Simply continuing what’s already underway will reduce emissions.

Joining The Global Methane Pledge Is An Easy Win

I’m not saying it would require no effort to cut methane emissions 30% over the next eight years. But I will say, thanks to declines in fossil fuel consumption and options available to reduce emissions from beef production and in other areas, it wouldn’t be difficult for Australia to meet the requirements of the Global Methane Pledge.

We should have joined and taken the easy win.

While our Prime Minister lacks the moral fibre to take any positive action to reduce fossil fuel consumption, he should at least have been devious enough to realize emissions will fall anyway and had Australia take the Pledge. He could have provided inadequate extra funding for emission reductions in agriculture, waste disposal and other areas, and allowed the inevitable decline in fossil fuel consumption do the rest.

But he couldn’t even manage that.

I know when it comes to climate change, Scott Morrison appears utterly unwilling to act in the interests of Australians and instead continues to put lives at risk for his own short term personal gain. He definitely gives the impression all he does is reject practical measures to reduce emissions, while going up on the world stage to take credit for cuts that occurred anyway.

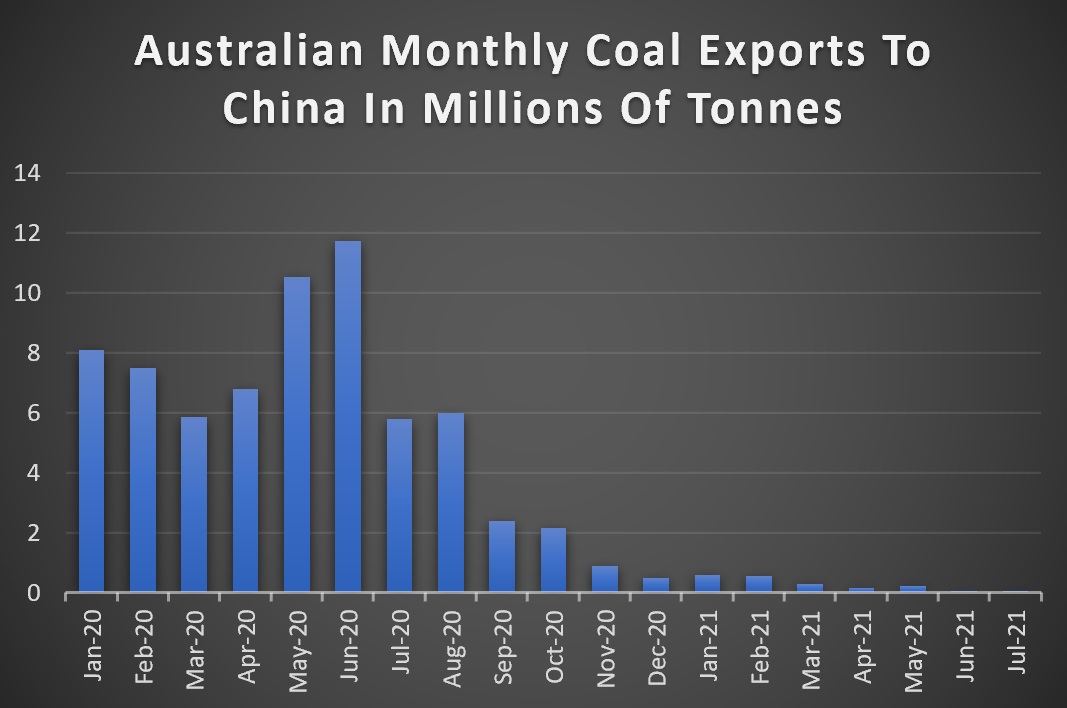

But I have to give credit where credit is due. He’s not completely useless when it comes to the environment. Scott Morrison has — single-handedly — caused more harm to the Australian coal industry than any other Prime Minister in history:

Information from KLER. Graphs showing Australian thermal and metallurgical coal exports to China can be found here.

[embedded content]

Footnotes

- Or 28 times as much warming, according to people using older figures or those who think it makes sense to take the bottom of a range of values rather than the middle. ↩

- If you see a much higher figure, that’s after it has been converted into CO2 equivalent. (Or the figure could just be wrong. That’s a possibility.) ↩

- Ending Australian coal generation over 5 years won’t be without challenges, but we seriously don’t have anything better to do. Apart from “Don’t die from COVID”, there’s nothing else marked down in our national five-year planner. ↩

- Fake meat made from plants also has the potential to reduce demand for beef and lamb — but I don’t see our government pursuing that as a policy. ↩

Original Source: https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/global-methane-pledge/