Top 10 Electric Car Myths Busted

Some people have strange ideas about electric cars.

I know because they’ve been kind enough to share them. I’ve collected so many I’ve made a Top 10 list.

Thanks to myths spread by people with inadequate regard for the truth, many are unaware of EV advantages. Myths are spread in dark corners of the internet and under bright lights by people working to be reelected. One example is Scott Morrison:

This is what our Prime Minister claimed a couple of years ago. He’s changed his mind since then, but don’t worry. I’m sure his change of heart is sincere. Just as I am, at all times, 100% sincere in everything I write.

Ending the weekend is not among my Top 10 myths because it was too stupid to make the cut. Many myths that did make the list contain a core of truth but either wildly exaggerate problems or ignore improvements made in the 11 years since the first modern, mass-produced electric car — the Nissan Leaf — was launched.

But other myths contain only a core of crazy. If those responsible ever got behind the wheel of an electric car, they’d head straight for Crazytown at ludicrous speed.

Electric cars aren’t perfect but are far better than some would have you believe. Despite all the myth-information, the days of conventional cars are numbered. Petrol and diesel vehicles are so bad I die a little inside whenever one drives by.

This is because their exhaust fumes are toxic.

My Top 10 EV Myths

Traditional Top 10 lists start at 10 and work their way down to 1. Well, screw that. I have no idea if information wants to be free, but it sure as hell wants to be organized. Otherwise, it’s merely data. I will present the myths in the order that makes the most sense for the reader, which means more important points first. But don’t worry, I’ll save a big one to finish on.

- You pay a large premium for an EV.

- Driving an EV emits more CO2 than conventional cars.

- Emissions from battery manufacture outweigh reductions from EV use.

- Batteries rapidly deteriorate and become useless within a few years.

- Electric vehicles have no or low trade-in value.

- We can’t recycle batteries.

- Switching to EVs wastes resources by causing conventional cars to be scrapped.

- Maintaining an old petrol or diesel car is greener than driving an EV.

- Charging electric vehicles is painfully time-consuming.

- EVs don’t have enough range — AKA “range anxiety”.

Myth #1. You Have To Pay A High Premium For EVs

Electric cars aren’t cheap. Especially not in Australia. So when I call out this myth, many people are going to call me crazy. There is a strong core of truth to this belief, and it’s the hardest for me to defend as being a myth — but I’m doing it anyway.

Right now1 the lowest cost petrol-powered car is around $17,000 while the cheapest electric car is around $45,000. So, if you are looking to buy a new car for under $30,000, you’ll have to pay 50% to 265% more to go electric. That’s a huge premium that definitely makes me look like a nutter.

The MG ZS EV is a nose charger with a real-world range of (hopefully) over 200 km. It will set you back around $45,000 on the road.

But the premium disappears — or mostly disappears — when EVs are compared to conventional vehicles of around the same price. This evaluation depends on personal preferences and driving habits so there’s room for disagreement, but I consider a Tesla Model 3 — which you can now get for around $62,000 — to be better than any petrol or diesel car of similar price. This is also true of the more expensive Tesla Model S. This is because they offer better performance and a quieter ride than the similarly priced competition.

Because Australians spend an average of around $41,000 when buying a new car, the half that spends more than this will generally either pay no premium or only a small one to get an EV. An electric car can save over $2,000 a year when driven the average annual distance2 The resale value of conventional cars is likely to drop dramatically over the next few years. Even if a sizable premium has to be paid, an electric vehicle could still be well worth it.

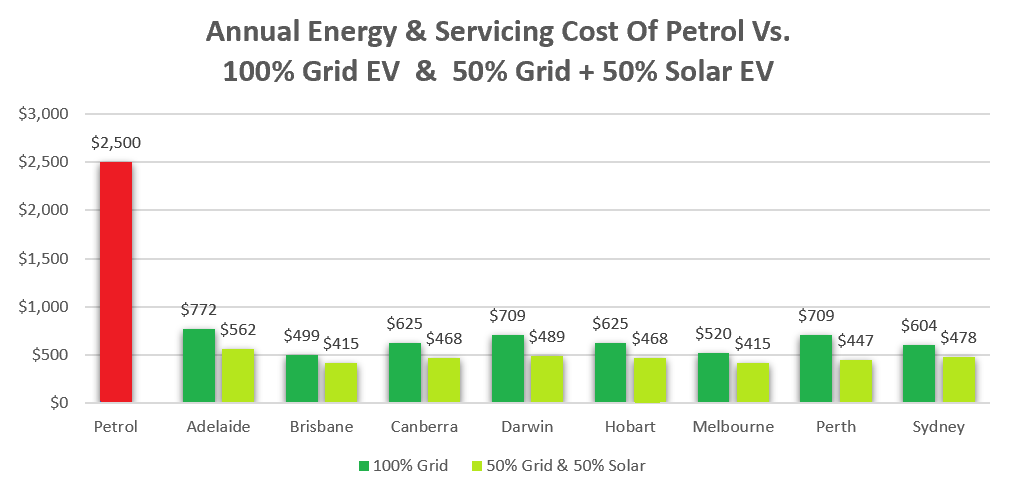

This estimates the difference in running costs between the average Australian passenger car and EVs when driven the average annual distance for the 2018/19 financial year of 12,600 km and a petrol price of $1.50 a litre. It varies by state and charging habits, but households with rooftop solar will often save over $2,000 a year.

Fortunately, the current situation where lower-cost electric cars aren’t available won’t continue. Manufacturers can supply them at a price similar to the cheapest conventional cars. For example, this is the Wuling Hongguang Mini EV:

Note: That lady is tiny. (Images: The Driven)

It has sold over 400,000 units in China. It seats four people, has a top speed of 100 km/h, and sells for around $7,000 after receiving little or no subsidy. Its real-world range is only around 140 km, but a version with over 300 km of official range is in the works. That should have over 200 km of range in real life.

Wuling Hongguang will never sell this car in Australia. It needs improvements in power, quality, and ability to handle the average Australian arse size. But it’s not hard to imagine an improved version being sold here for around $17,000 in a few years — the same as the cheapest petrol-powered cars.

Myth #2. EVs Emit More CO2 Than Petrol & Diesel Cars

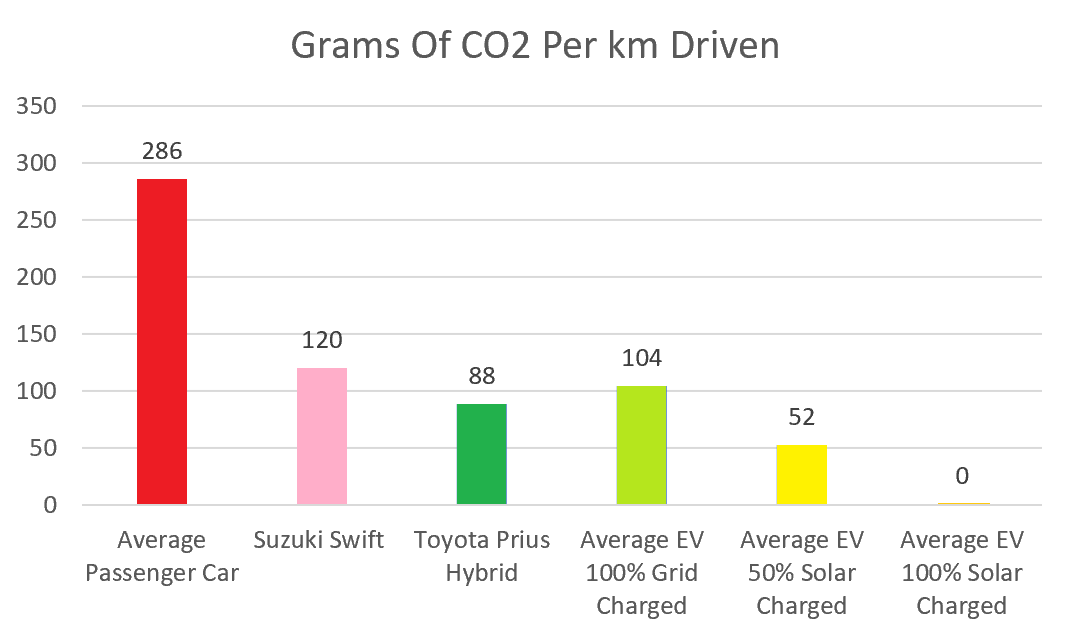

The idea that driving electric cars results in greenhouse gas emissions equal to or greater than conventional cars is crazy talk. There’s no core of truth to this myth. The best that EV sceptics can claim is an electric car charged from a grid that’s heavily dependent on old coal power stations may be worse than a similar-sized fuel-efficient hybrid or a considerably smaller conventional car. Even this won’t last as grids are becoming cleaner.

It’s not difficult to determine the approximate emissions of an EV charged from Australia’s dirtiest grid…

- Including losses, an electric car needs to be charged with around 0.15 kilowatt-hours per km driven.

- Victoria has Australia’s dirtiest grid and, over the past year, emitted around 1 kg of CO2 per kilowatt-hour supplied.

- This gives an average of 150 grams of CO2 per km for an electric vehicle charged from the Victorian grid.

If we do a similar calculation for a petrol-powered vehicle…

- The average Australian passenger car burns 0.11 litres of petrol per km.

- Including emissions from extraction, refining, and transport3 — petrol emits around 2.6 kg of CO2 per litre burned.

- This comes to an average of 286 grams of CO2 per km.

So even when charged from Australia’s dirtiest grid, a typical electric car will only result in 52% the CO2 emissions of the average Australian petrol passenger car. If the car is charged 50% from rooftop solar4 it drops to only 26% the emissions of the average car and less than any hybrid vehicle on the market.

If we use the average grid emissions for Australia of around 690 grams of CO2 per kilowatt-hour5 it comes to 104 grams. This is more than the 90 grams per km, which is around the best a fuel-efficient hybrid can do in real-world driving, but an EV would only have to be charged 15% from rooftop solar panels to do better.

This graph shows the grams of CO2 emissions that result from driving 1 km. The Australian average of 690 grams of CO2 per kilowatt-hour supplied for grid generation was used.

Given the amount of additional solar panels people are installing on roofs in preparation for EVs, the average electric vehicle will have no problem beating even the best hybrid on emissions per km. Also, because I’m expecting coal power stations to be closed at an accelerated rate, I’m certain the typical electric vehicle bought today and only charged with grid electricity of average filthiness will have lower emissions per km over its lifetime than the best currently available hybrid.

Myth #3. Emissions From Battery Manufacture Outweigh Any Benefits

I’ve shown EVs don’t emit more greenhouse gases than conventional cars per km driven. But there’s another myth saying the manufacture of EV battery packs releases more emissions than driving saves. While the production of the battery pack is emission-intensive, it doesn’t come close to outweighing electric vehicles’ emission benefits.

A recent estimate put emissions from EV battery pack manufacture at the equivalent of 75 kg of CO2 per kilowatt-hour. This is terrible. If true, it means producing a 50 kilowatt-hour battery pack results in greenhouse gas emissions equal to 3.75 tonnes of CO2.

But an EV charged entirely from the Australian grid will, on average, result in around 182 grams less emissions per km than a conventional car. This means it would only have to be driven around 20,600 km to pay off the emissions debt from its battery pack. As the average Australian car is driven 12,600 km a year, that’s around 20 months. If the electric vehicle was instead 50% charged from rooftop solar, it would only have to be driven around 16,000 km — around 15 months of average driving.

But emissions from producing the battery pack don’t tell the full story because manufacturing the rest of an EV results in less emissions than for a conventional car. An electric motor is much simpler and lighter than an internal combustion engine, and EVs don’t require fuel tanks and exhaust systems. This means manufacturing emissions aren’t as bad as just looking at the battery pack suggests.

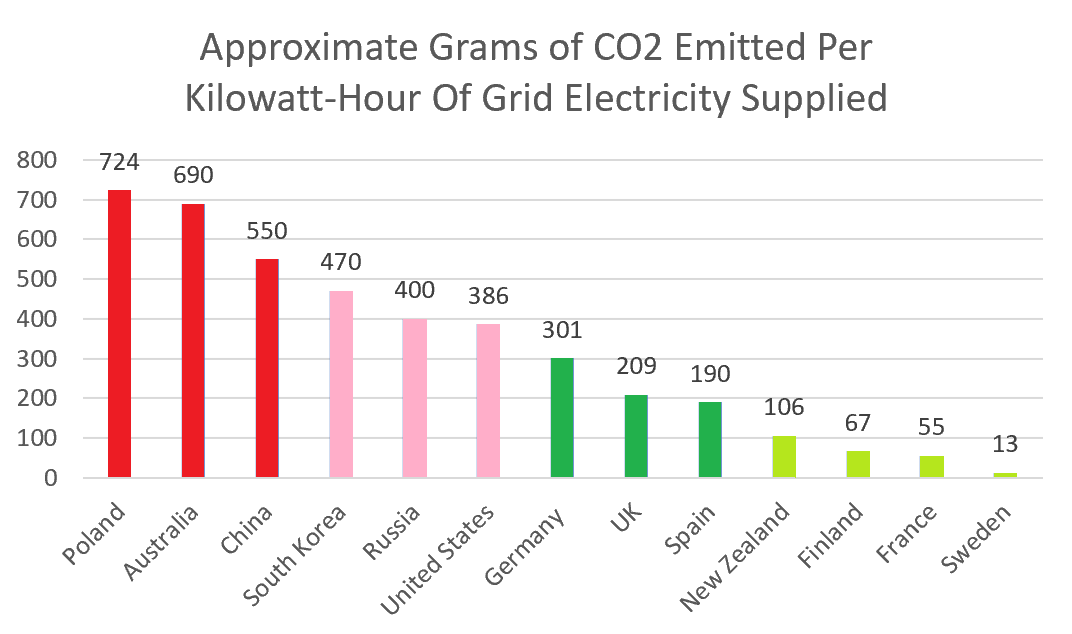

In their 2020 Impact Statement, Tesla says the their Model 3 with a 50 kilowatt-hour battery pack must drive only 8,600 km to compensate for the additional emissions compared to the manufacture of a comparable conventional car. That distance is eight months average driving in Australia, but I’d expect it to be less as our grid emits more CO2 per kilowatt-hour than almost every other country.

Poland may be the only developed country with higher grid emissions per kilowatt-hour than Australia.

Emissions per kilowatt-hour of battery capacity produced are falling and will continue to fall. This is because manufacturers are always seeking ways to reduce energy and material inputs to cut costs, while energy is becoming cleaner. Tesla claims they will decrease the energy required to produce their new 4680 battery cells by over 70%. While Tesla is a company that often exaggerates, I’m certain emissions from battery manufacture will fall in the future. I wouldn’t be surprised if they were already significantly under 75 kg of CO2 per kilowatt-hour.

4. Batteries Deteriorate Rapidly

Another myth is EV batteries deteriorate rapidly. Some say they’ll be knackered after only five years, while others very confidently make the very vague claim they’ll only last “a few” years. This view is clearly not based in reality, as all major electric vehicle manufacturers provide far longer battery warranties:

- Tesla Models S and X: First of 8 years or 240,000 km while retaining 70% capacity.

- Tesla Model 3 Long Range and Performance versions: First of 8 years or 192,000 km while retaining 70% capacity.

- Tesla Model 3 Standard Range +: First of 8 years or 160,000 km while retaining 70% capacity.

- Nissan Leaf: First of 8 years or 160,000 km

- MG ZS EV: 7 years with unlimited km for non-commercial use.

- Hyundai EVs: First of 8 years or 160,000 km.

You can expect an EV battery pack to last at least as long as its warranty. If it doesn’t, you’re entitled to a repair, replacement, or refund. Unless, of course, the company’s no longer around because it went bankrupt from the cost of replacing lousy batteries.

Just as you can expect the engine in a conventional car to last well beyond its warranty period, you can expect an electric vehicle battery pack to do so as well.6 If we assume a battery will last 160,000 km — the lowest km distance in the warranties above — that’s nearly 13 years of average Australian driving.

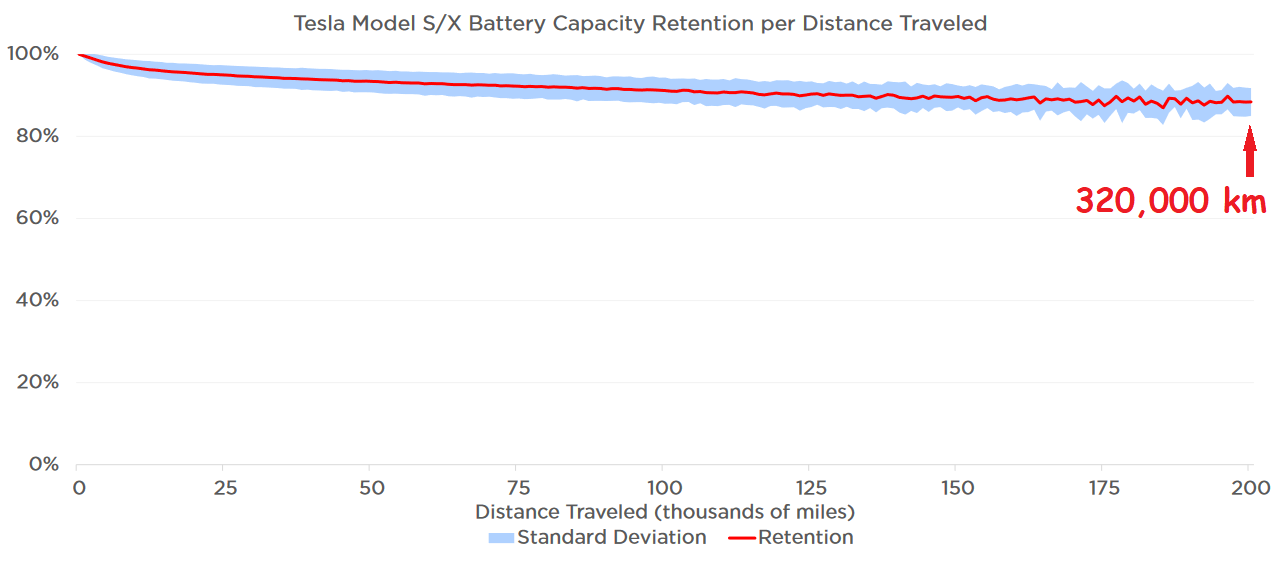

But the typical battery pack may last longer than that with only moderate loss of capacity. Here’s a graph showing the capacity of Tesla S and X EVs averaging around 89% capacity after 320,000 km:

This graph is from page 22 of Tesla’s 2020 Impact Report. (I added the red comic sans myself.)

This represents 25 years of driving for the average Australian passenger car, which is a lot longer than Aussie cars usually last.7, so it definitely looks as though batteries can last a long time.

But because Tesla likes to spin things as positively as they can, there are a couple of things the graph above doesn’t point out that may result in the average EV battery pack suffering greater capacity loss:

- The graph shows results for large 100 kilowatt-hour battery packs. A 50 kilowatt-hour battery pack, which is closer to what most EVs have, would have to be cycled twice as much to drive the same distance, assuming the same energy consumption per km. This could cause twice as much degradation from cycling. Capacity loss can be further increased if a smaller battery pack provides higher power output per kilowatt-hour of storage.

- This information comes from Tesla vehicles that were driven a high number of km per year. This means capacity loss may be greater for the typical car driven the average distance per year.

While things may not be as good for the average EV as the Tesla graph suggests, if battery capacity loss is three times the rate shown, it will still have two-thirds capacity after 25 years. While any loss isn’t good, it’s nowhere near as bad as the myth would have you believe. I’m not saying you can count on an EV battery lasting 25 years. Modern battery packs haven’t been around long enough for us to know. But I’m confident most electric vehicles sold today will still have their original battery in 15 years and they’ll have only suffered moderate capacity loss.

Myth #5. Electric Vehicles Have No Trade-In Value

One myth is EVs have low or even no trade-in value. There is some truth to this. Electric cars will continue to improve, which will push down the trade-in value of an EV you buy today. But it’s a stupid myth because if electric cars continue to improve, it’s going to push down the trade-in value of internal combustion engine vehicles even further.

This myth likely got started for the following reasons:

- The first modern, mass-produced electric cars that began to appear 11 years ago were often expensive for what you got and so were mostly bought by enthusiasts. This meant they received lower prices on the second-hand market, who are mostly people who can’t afford to be too enthusiastic.

- Many of the first electric cars had limited ranges, and some, such as the original Nissan Leafs, suffered battery deterioration problems.

- Many countries had EV subsidies, but in places like the US, the subsidy was received after the vehicle was bought. This made it appear electric vehicles were taking a larger hit to their trade-in values than they were.

- Unfamiliarity — people without a lot of money to spare don’t want to take a chance on a new type of car their uncle won’t know how to fix.

- EVs were improving rapidly, which meant people would often wait to buy a new model rather than purchase a second hand one.

But these issues mostly no longer apply. While new models of EVs will continue to improve and lower-cost models will appear, and this will hurt the trade-in values of today’s EVs, internal combustion engines will be hurt even more. This is because electric vehicles are — for the majority of people — a superior product.

Once EVs have demonstrated they break down far less often thanks to electric motors being so simple, have much lower running costs, and their batteries can last long term, demand for second hand EVs is likely to be far stronger than for conventional cars.

Petrol and diesel cars are also a risky proposition from an environmental regulation point of view. While the oil price may fall as EVs become increasingly common, global warming isn’t shaping up to be something we don’t need to worry about. This means conventional car drivers may end up paying for their carbon emissions. If it costs $80 to remove a tonne of CO2 from the atmosphere and sequester it long term — a very low estimate — that will add around 21 cents to the price of a litre of petrol.

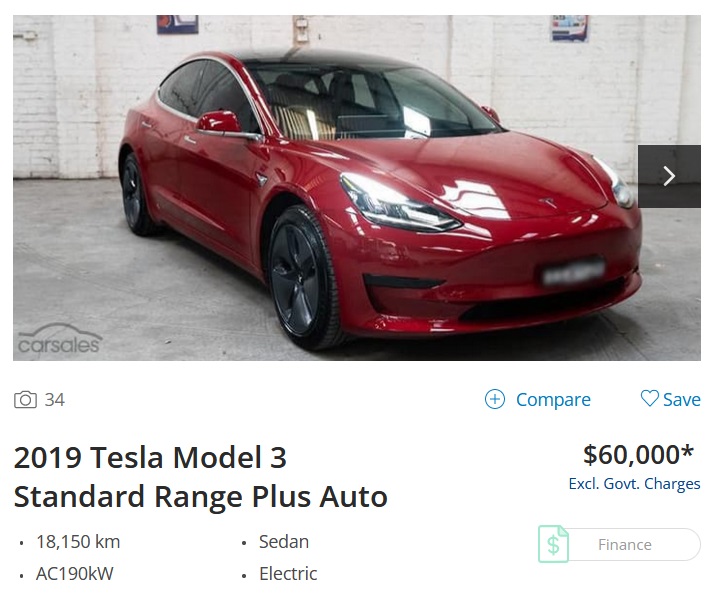

This electric vehicle is on sale for 3% less than the price of a new one, so clearly, at least one person thinks they retain value.

Myth #6. EV Batteries Can’t Be Recycled

One myth is EV batteries can’t be recycled. But they can and will be because there’s valuable stuff inside. The main material is stainless steel and, by weight, steel is the most recycled metal in the world. They also contain copper, which is in such strong demand by recyclers my entrepreneurial friends, Pigdog and Spider, accept it in lieu of cash in their business transactions.

Other elements such as lithium, cobalt, and manganese require specialized equipment to recover, but they can be collected by recyclers as mixed metal dust that’s shipped off for further processing. Alternatively, battery packs can be returned to their manufacturer to be directly recycled into new ones.

The current per kg costs of metals in a battery are:

- Steel scrap: $1.07

- Copper scrap: $5.90

- Cobalt, refined: $112

- Nickel, refined: $28

- Manganese8, refined: $2.80

- Lithium as carbonate (16.7% lithium by weight): $205

Lithium has quadrupled from its price in 2020 and is at a record high. This is expected to cause a shortage of at least some brands of home batteries in Australia over the next few months and may affect the supply of EVs. Happily, it will also increase the focus on recycling. The price spike won’t last, but improvements in recycling will.

While it’s technically possible to reuse everything in a battery pack, it’s not economical for some materials such as carbon — which is very cheap. Some people will be upset that not everything is recycled, but it makes no sense if the money would do more good elsewhere, such as solar energy and wind generation.

Myth #7. EVs Waste Resources By Causing Old Cars To Be Scrapped

One odd myth is EVs require petrol and diesel vehicles to be scrapped and so waste resources. I’d agree if conventional cars in good working order were being scrapped, but this isn’t what happens.

When you decide to buy a new electric car rather than a new conventional one, your decision results in one more EV being made than would otherwise occur and one less internal combustion engine car being made. Buying a new electric vehicle doesn’t result in a new conventional car being hauled off to be scrapped. It displaces them, so they never exist in the first place and never consume resources.

This myth may have been fed by the “Cash for Clunkers” program in the US. This was a subsidy for automakers wrapped in the skin of a dead environmentalist as a disguise. This scheme ended 11 years ago and resulted in the sale of very few EVs, as not many were available in 2009.

I know no country currently paying people to scrap conventional cars and replace them with EVs. If you trade in your still running six-year-old car for an electric vehicle, the car yard isn’t going to send it to a wrecker. They’re going to sell it for as much money as they can get.

If demand for conventional cars falls so far ones currently considered roadworthy end up being scrapped, that’s not a waste of resources. That’s freeing up resources, such as steel, trapped inside a vehicle that’s obsolete thanks to technology, making EVs clearly superior in terms of quality, running costs, and reliability.

Myth #8. Maintaining An Old Car Is Better For The Environment Than Buying An EV

Related to the previous myth is the odd idea maintaining an old car is better for the environment than buying an EV. This comes in two main flavours:

- The additional CO2 emissions from making an EV are so high it’s better to keep your old car operating.

- Greater emission reductions can be achieved by spending the money elsewhere, such as on solar power.

The first point doesn’t make sense. As I showed earlier with myth number three, it doesn’t take long for an EV to make up for the additional emissions that result from its production thanks to lower emissions from each km driven — which can be zero when charged with clean energy.

Any comparable conventional car will emit more emissions every km, and these extra emissions will occur until it’s replaced with something better, such as an electric vehicle. No benefit ever occurs from keeping a conventional car running unless it benefits your bank balance from not shelling out for a new car.

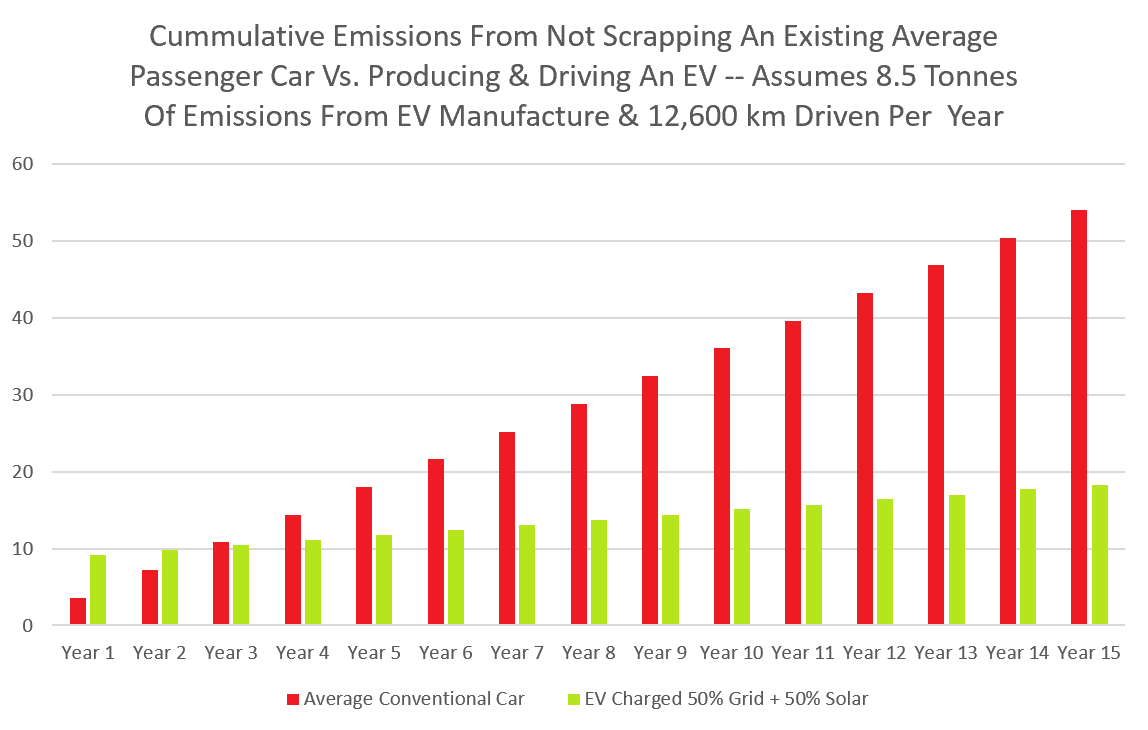

This graph is stupid, not because it assumes there are no CO2 costs for oil and spare parts required to keep an existing conventional car running but because it ignores the grid will become cleaner over time. It’s stupid because if a conventional car is still roadworthy when it’s replaced, it will — in the vast majority of cases — be sold and used rather than scrapped. But even with the assumption, it suffers existence failure if an EV is bought. The conventional car’s cumulative emissions from driving alone are greater after three years than manufacturing and driving an EV.

The second version of this myth is true. There are options providing far more environmental benefit per buck than buying an electric car. For example, buying a large solar system will cut emissions far more than spending the money on an EV, and I heartily recommend this course of action.

If you do this, you won’t have a new car, so you will be making a sacrifice. You may have a conventional car you can keep operating, but eventually, it will wear out and need to be replaced. As there are likely to be plenty of second-hand electric cars on the market by the time this happens, the sensible thing to do would be to replace it with one of them.

So please spend a lot of money on solar power and potentially other better ways of helping the environment before you spend money on an EV, but if you are going to spend a considerable amount of money on a car, then please make sure it’s electric — or at least a fuel-efficient hybrid – if that’s a better match for your driving habits and budget.

Myth #9. Charging An EV Is Time Consuming

One myth that never seems to run out of energy is EVs are time-consuming to charge. When this one’s brought up, it always seems to be in the context of a long trip of hundreds of km or more to a remote outback town. Some things these hypotheticals often ignore are:

- Many electric vehicles have a longer range than myth spreaders realise9.

- Many EVs can use high power DC chargers which I’ve seen add a dozen km of range in a minute. With the right car and right charger, it can apparently now add 100 km of range in 5 minutes.

- The less energy remaining in a battery pack, the faster it charges. This means charging to less than full can save time.

- Human beings need to take a break from driving every now and then — or at least they should.

- Most Australians don’t travel to remote outback locations. From the way some people write about EVs and range, you’d think Cunnamulla was the place to be, but trust me, you can go to Cunnamulla and wait a very long time for someone who isn’t a local to show up. People who drive long distances in the outback are smart enough not to buy an electric vehicle that isn’t suitable for the task.

It is true on a long trip, even EVs able to be rapidly charged take considerably longer to “fuel up” than a petrol or diesel vehicle. What makes this a myth is the underappreciated fact most electric vehicle owners spend less time “fueling” than those with conventional cars. This is because normal day-to-day charging takes so little time.

When the typical EV owner gets home, they spend under 30 seconds plugging in their car and the next day spend under 30 seconds unplugging it. They may spend less than 5 minutes on this in a typical week, while a service station visit is usually at least 10 minutes. If an EV owner comes out only 5 minutes ahead per week, that totals over 4 hours a year. This could be split into a dozen 20 minute sessions of rapid charging. With a suitable car, this could add over 2,000 km of range.

But the actual comparison is better than this. This is because a lot of charging time isn’t wasted but is spent peeing, eating, sightseeing, or reducing fatigue until it’s safe to drive again.

It will depend on driving habits and the type of EV owned, but assuming one that matches the driver’s needs is used, the typical electric vehicle owner should come out ahead on time spent fueling.

Myth #10. EVs Don’t Have Enough Range — AKA “Range Anxiety”

Range anxiety is not a myth. It is something that exists. But a major reason why people have it is they fall for the myth that EVs don’t have enough range for the typical driver.

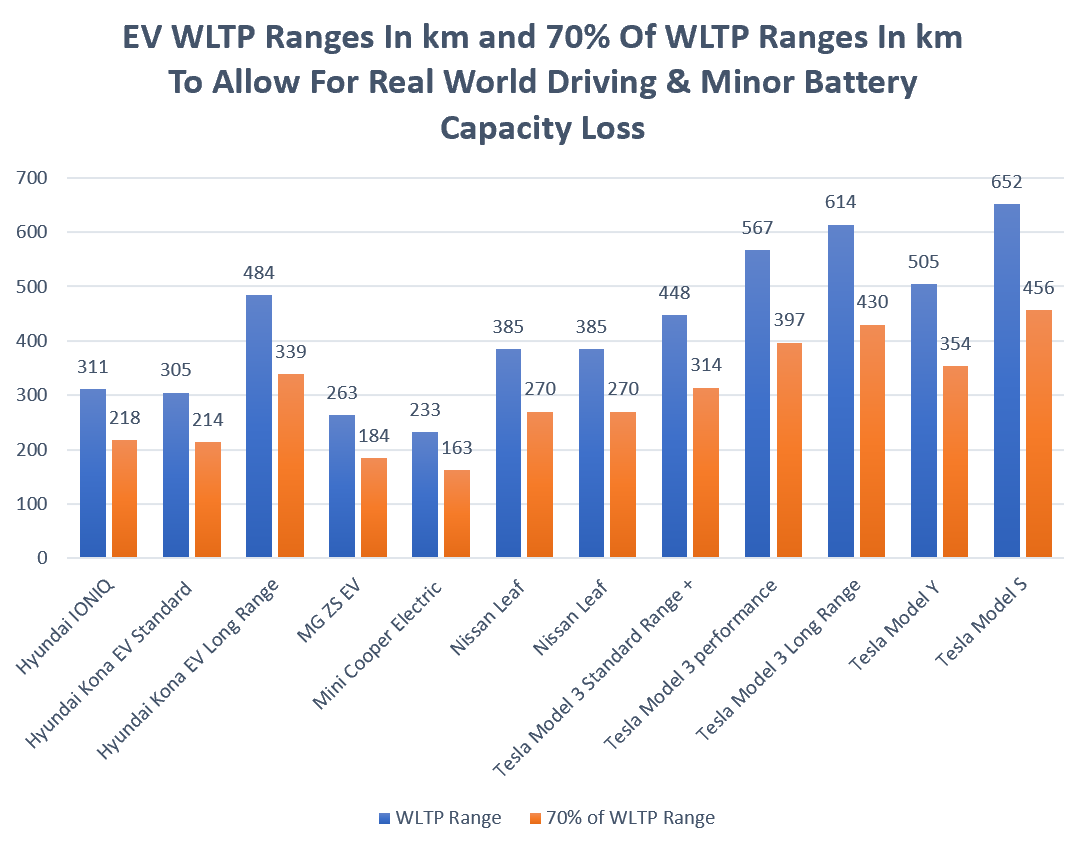

There are several EVs available with real-world ranges of over 300 km. This is more than enough to suit the majority of Australians. As mentioned in the previous myth on charging times, the typical electric vehicle owner spends less time charging than a conventional car owner spends putting fuel in the tank.

It’s possible to buy an EV without enough range to meet your needs, and this will force you to charge at inconvenient times. But it’s also possible to buy a pair of pants that are too small. Simply ‘not buying pants’ to avoid this possibility would be stupid.

WLTP stands for World harmonized Light-duty vehicle Test Procedure. It does not give a realistic result, so I have included 70% of its figure on the graph above to allow for real-life driving conditions reducing range, as well as minor battery capacity loss. EV manufacturers normally know exactly how much range their cars get in normal use, but they keep these figures to themselves. (While I still gave a 70% figure, user reports put Hyundai EVs closer to the WLTP figure in real-world conditions than other major brands I’ve looked at.)

It is true, thanks to their lower maximum range and longer refuelling time, EVs can add to the time required for longer trips. But when their other advantages are considered:

- Less time spent fueling overall for typical drivers.

- Lower running costs.

- Greater reliability thanks to the simplicity and durability of electric motors.

- Usually better performance than comparably priced conventional cars.

- A far quieter ride.

People should be suffering ICE anxiety over how their Infernal Combustion Engine cars are causing them to miss out on all this.

Don’t Believe Myths — But Don’t Fall For Hype

That was only my Top 10 list for EV myths. There are plenty more out there, so be wary of falling for any I didn’t mention. Unfortunately, plenty of people are willing to deliberately mislead and even happier to repeat something that sounds good without checking if it actually is.

But the prevalence of myths is partly due to EV manufacturers themselves. For example, rather than simply giving the real-life range people achieve in their cars – something they have exact information on – they give the results of tests that don’t reflect real-life driving in a deliberate attempt to mislead people into thinking their vehicle’s actual range is better than it is.

This is a real pity because, after the emission scandals by Audi, BMW, Daimler, Porsche, and Volkswagen, there was a great opportunity for EV manufacturers to position themselves as the honest alternative. But they failed to do so. Hyundai appears better than the average EV maker when it comes to honesty but, who knows? If I could read Korean, maybe I’d change my mind.

So while it’s important not to fall for electric vehicle myths, you should also watch out for EV hype. Current EVs are worthwhile for most Australians who spend the average amount or more on a new car, but it’s vital to do your research because you can’t trust car manufacturers. Not even electric ones.

Footnotes

- Actually, due to supply problems, you may have to wait a while for your new car to arrive. ↩

- The average Oz passenger car was driving 12,600 km in the 2018/19 financial year. ↩

- Going from oil in the ground to petrol in a tank increases emissions by around 13%. This doesn’t include embodied emissions in oil infrastructure. I also haven’t included the small amount of embodied emissions that could be applied to each kilowatt-hour of grid or rooftop solar generation. ↩

- To be nitpicky this should be additional solar power capacity and not existing solar capacity, as existing capacity is already reducing emissions. But plenty of people are installing extra-large solar systems because they have or are planning to get an EV. ↩

- A more optimistic figure puts Australia’s grid emissions at around 650 grams per kilowatt-hour, but I can’t work out how it was determined, so I’m using the more pessimistic 690 gram figure. ↩

- A 50 kilowatt-hour battery pack in an EV that has been driven 160,000 km will only have been fully cycled around 500 times. This is very different from home batteries which typically have warranties covering thousands of full cycles. ↩

- The average age of passenger cars on the road is around 10.6 years. But because the number has increased with rising population and wealth and because commercial cars that get driven many km bring down the average, most cars in private hands from when they’re first bought last longer than that. ↩

- This stuff litters the oceans, so while it’s called a rare-earth element, it’s not rare. ↩

- I’ve also seen people assume an EV will start with an empty battery pack and will have to spend time charging before it can go anywhere, just like people always drain their petrol tanks before going on a long trip. ↩

Original Source: https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/top-10-electric-car-myths/