Conduit & Solar Inverters: The Good, Bad & Fugly

Looks fine from my house…

The $200, 2-inch thick, spiral-bound ‘AS/NZS 3000 Electrical Installations’ is also known as The Wiring Rules, The Book, or The Bible. Electricians use it to beat each other over the head when they feel a fellow sparkie has strayed from the true path of holy electrical compliance.

In the same way that electricity seeks the path of least resistance, some tradies will bend or ignore the rules in The Book that a proper tradesman1 will follow.

The 50mm-Or-Conduit Rule

One of the Golden Laws outlined in The Book is ’50 millimetres’. Electrical cables in a wall must be more than 50 mm from the surface. The concept is that, even if wiring is hidden behind a surface, it will still be quite safe to drive a 2-inch nail into that surface.

But what about screws bigger than 50 mm? They are the reason it’s illegal to fix or restrain wiring inside a wall cavity. If you unknowingly attack the cables with a 75mm screw, the cables should be free to move aside.

What happens when you can’t place your cables 50mm from the surface? Then extra protection is required, most often conduit in a variety of forms; but sometimes a continuous sheet of steel can be a more subtle solution.

The Conduit-For-Solar-Cables Rule

Now for solar cables, there are even more rules…

My previous post explained that solar DC cables must be encased in heavy-duty conduit as soon as they enter the roof cavity. That rule continues all the way to the inverter. Even if the DC cables go down the wall inside a double brick cavity, conduit is required.

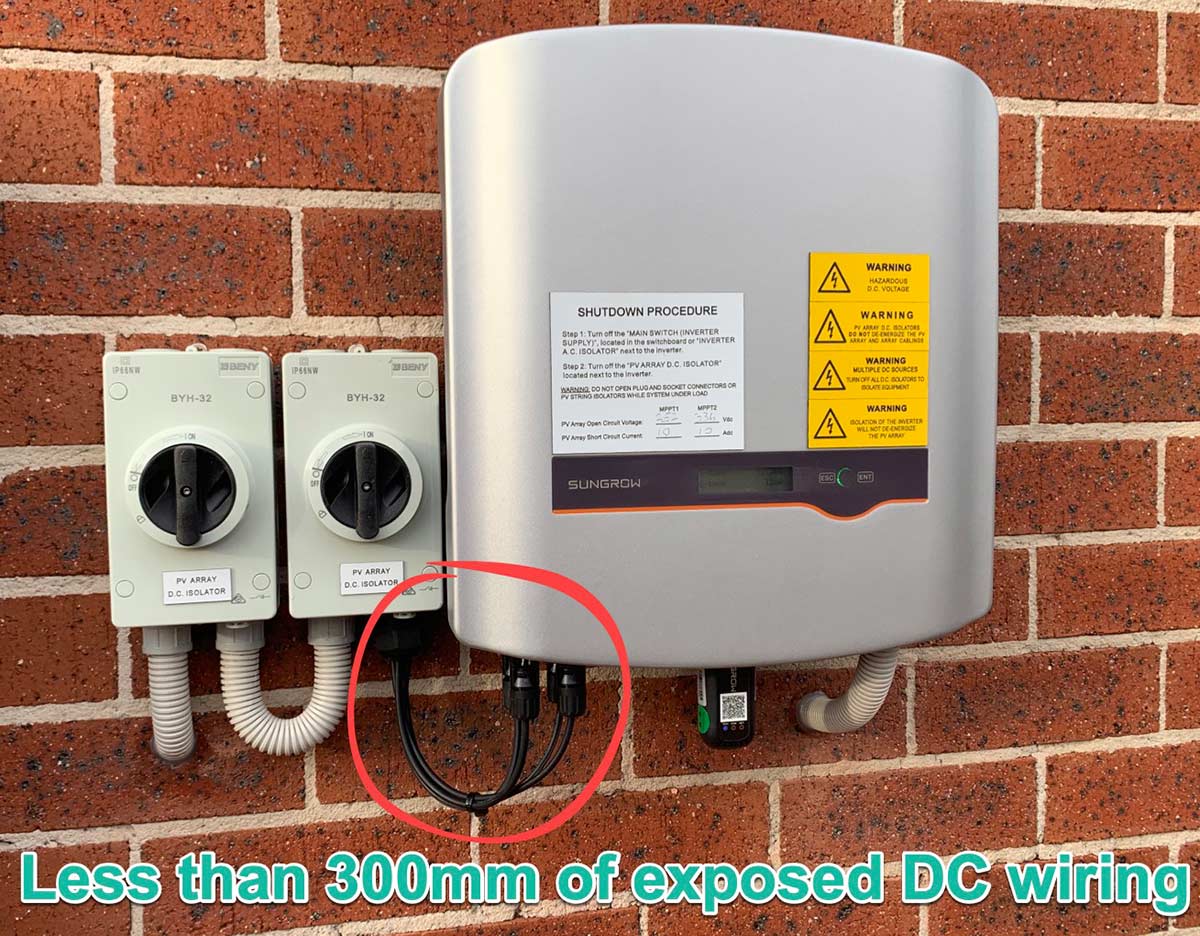

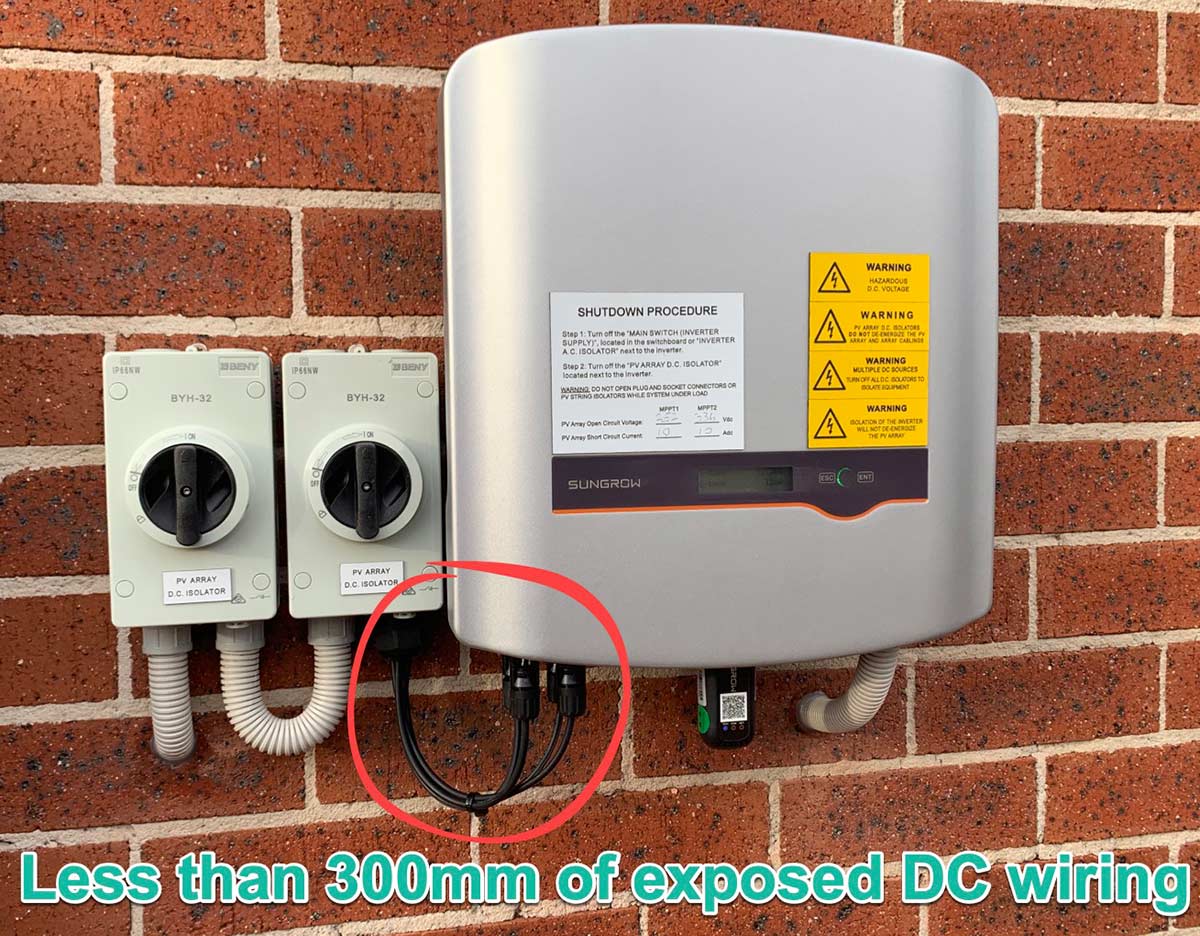

Once the conduit reaches your isolator, it must enter from the bottom. The solar inverter (known as Power Conditioning Equipment or PCE for those fans of TLAs) might have plugs or conduit entries, but either way there can be no more than 300mm of DC cable exposed for your dog to chew on.

The Drain-Valve-In-Your-Conduit Rule

One rule that has recently caused some in the industry to insert an expletive before describing the actions of the Standards Committee relates to drain valves.

Yes, I know that sounds more like a plumbing standard.

Thing is, with all this mandated conduit, the solar standard in effect decrees that we install plumbing from the roof (where it’s wet) to the electrical equipment (where there’s stuff we’d really like to keep dry). To mitigate the inevitable effects of condensation filling the lowest point with water, (usually the inverter or isolating switch) new standards specifically prohibit the simple, age-old practice of weep holes being drilled. The new standard requires either the conduit to be left open at the inverter end (simple) or drain valves to be installed. When the standard came out, these devices were not even available. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

[embedded content]

[embedded content]

The Mechanical-Protection-Or-RCD Rule

Solar AC circuits get a special mention in Australia. The latest AS3000 mandates any ‘final subcircuit’ SHALL have earth leakage protection. In layman’s terms, unless it’s a feed from one switchboard to another, it has to have a safety switch and the local rules call for these Residual Current Devices (RCDs) to trip when they see a 30 milliampere imbalance.

Now, the issue is that solar inverters are fundamentally leaky devices. To prevent nuisance tripping, some inverter manufacturers specify that if you use an RCD it should have a rating over 3 times higher. So, who do you believe? As a solar installer, it’s embarrassing to have a system that intermittently trips off due to antipodean rules.

Some (including the Clean Energy Council) argue pragmatically that a final sub-circuit is defined in The Book as having ‘consuming loads’, and a solar power system is a generator – so the AC wires powering a solar inverter are not a final sub-circuit. They treat it like millions of existing installations, as an unprotected circuit with a normal circuit breaker and it’s happy days.

Other readers of The Bible point out that an inverter does consume energy as well as generate it, so its supply circuit is a final sub-circuit and needs that RCD.

What are the rules for if not for interpretation?

And what has this got to do with conduit?

Well, even if you think you don’t need an RCD for the inverter supply; another clause in the inverter installation standard (AS4777.1. Sec.3.4.5) says: if the solar inverter’s AC cables are not 50mm from the surface and they are not free to move aside for errant drill bits, then they must be very well mechanically protected – for example with armoured conduit.

But if that is not possible, you can protect the inverter supply circuit with a 30mA RCD. But it has to be a 30mA RCD, and the inverter manufacturer cannot override this.

In reality, this means – if your solar inverter cannot use a 30mA RCD because of nuisance tripping – then you need to use armoured cable (commonly described as anaconda) or heavy wall metal conduit (think galvanised water pipe) The issue here is that this level of protection is literally the industrial standard for explosive environments such as fuel refineries, so it comes with industrial level difficulty and expense.

As alluded to earlier, there is a simpler workaround that has some cost, but some benefits as well. You wouldn’t have noticed the last time you went to the dentist, but scratch through the plasterboard and you’ll find sheet metal lining the walls (which serves as X-ray radiation shielding).

We can’t show you his face, but this dentist does a better steel wall fit out than the tradies who charge $100 000 per dental room.

If your electrician can manage a sheet of 1.6mm steel as wall cladding then they can run an unprotected AC circuit for the solar inverter behind it. If they can’t, then I’ll give you the number for my dentist.

This can also serve as a non-flammable barrier for a home battery installation and personally, I like the spangled appearance of galvanised iron over cement sheet, though both can be painted.

Surface Conduit Vs Hidden Cables

Sometimes it’s simply not possible, practical or cost-effective to hide everything. If you have a single-leaf brick wall, solid stone or concrete, perhaps a two-storey house with no access to a cavity, then what you really need is a talented tradesman who owns a conduit bending spring and knows how to use it.

Custom-made curves in rigid conduit for easy cable installation without elbows, junction boxes & dozens of fixings

As an electrician who enjoys setting a precedent and doing genuinely neat work, I like it when I can bring home the steampunk ambience of your local cafe, to embrace the industrial style of arts and crafts.

DC wiring executed simply with service loops in the solar inverter and custom-shaped conduit with label.

For those tradies who are incapable of any craft, (believe me there are many, the time-is-money ethos breeds them) or the customers who prefer the superficially tidy, you can just have everything hidden inside plastic air conditioning duct or metal cable tray and lid.

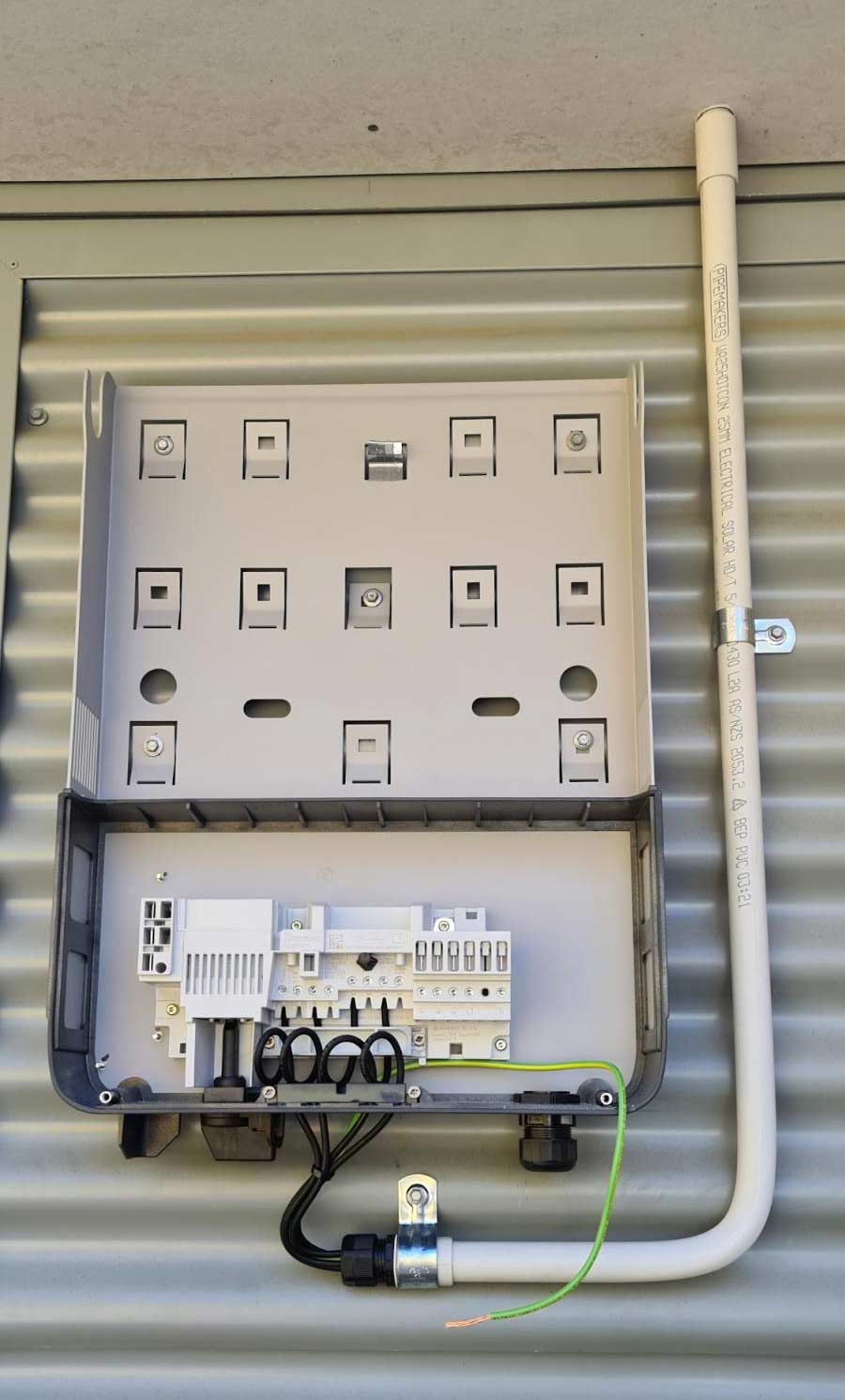

Metal tray can be the answer to cable management but this solar inverter manufacturer (Sungrow) hasn’t given inverter connections much thought. The battery pictured is well resolved though.

What About Micro Inverters?

Now before the “Enphase Evangelists” start (they’re the solar industry’s answer to vegans, bless them), I should mention that many of the issues outlined in the article are avoided by running an AC circuit and using micro-inverters behind the panels on the roof. Enphase evangelists have a point but they don’t always have the answer.

So, When Do You Have To Use Cable Conduit?

As a rule, when your electrician dictates it is a requirement for a compliant or reasonably speedy install.

If you really care a great deal about the appearance of your finished job, be sure to advise your sales rep or electrician before installation day. Hatch a plan with them and be prepared to pay some extra if it needs a powder coated cable tray or a well-ventilated solar inverter cover to look slick.

Look, Mum, no wires! Sadly this aesthetic would soon be ruined with red and yellow warning labels.

Footnotes

Original Source: https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/cable-conduit-solar-inverters/