Battery Test Centre 8th & 9th Reports: Many Home Batteries Still Unreliable

Ronald analyses the latest battery test results just as you like it. This twice-told tale shows the course of true battery love may not run smooth.

Do you enjoy reading about home batteries? I know I do. This is why I’m addicted to reports from the Canberra Battery Test Centre. They’re like Shakespeare! That is, they’re mostly tragedy but there’s also some comedy as well. You couldn’t ask for a better demonstration of the best-laid plans of mice and men going awry than the tale they tell of the sky-high failure rate of home batteries.

The Test Centre’s most recent report was the 9th, which came out in September last year. I’ll quickly cover its highlights and also give some information from their 8th report published in April. Because it has taken me so long to get around to writing on them, I was tempted to hold out for their 10th report, but as I was asked to give an update on their results, here we go.

The main points I’ll cover are:

- The most relevant and/or interesting information from their older Phase 1 and Phase 2 battery testing.

- A description of their latest round of Phase 3 testing and how well/badly the newest batteries have held up so far.

- Trends identified by the report.

- My own brilliant but brief, conclusion.

But first, I’ll explain what the Canberra Battery Test Centre is, to bring up to speed anyone who doesn’t know what I’m blathering about.

What The Hell Is The Canberra Battery Test Centre?

As you’ve probably guessed, the Canberra Battery Test Centre is a Centre in Canberra that tests batteries.

It’s run by ITP Renewables who received a fistful of your taxpayer dollars to perform accelerated testing of home battery systems and report on how well they perform. They cycle batteries three times a day under controlled temperatures designed to simulate real-world conditions. Each cycle consists of fully charging a battery and then discharging it by the maximum allowed for normal use.

The idea is, assuming a battery is cycled an average of once a day in actual use, they can inflict 10 years worth of wear and tear on a battery in around 3 years and 4 months. This approach isn’t perfect, but it’s necessary to do something along these lines if you want information within a reasonable period.

A major limitation is they only test one of each type of battery, not counting replacements. This means it’s possible they just happened to get one battery in a thousand that’s defective or possibly the one in a thousand that happens to work as it should. This means if a particular battery performs poorly, it may simply have been bad luck. But given the number of batteries tested so far, it’s safe to conclude home batteries, in general, are unreliable.

Past Articles Detail Poor Performance

More details on testing can be found in the four articles I’ve already written on previous Battery Test Centre reports:

The first article has a Star Wars vibe while the fourth riffs on Monty Python, but the common theme running through them all is home batteries are surprisingly failure-prone. Of the 18 from the first two phases of testing, only three worked as they should have. I’m not saying three of the batteries worked really well; I’m saying only three operated as designed without failing in some way.

Some had minor problems and functioned after being fixed, while quite a few performed the not-at-all impressive magic trick of turning themselves into expensive bricks. There’s also one that started as a tragedy by needing to be replaced but became a comedy of errors by repeatedly failing, and the Test Centre is now onto its fifth unit. But its manufacturer gets full marks for perseverance.

Large Manufacturers Have Many Faults

While there were some utter disasters with batteries from small suppliers on account of a couple of companies going belly up and taking their warranty support with them, buying from a large manufacturer was no guarantee of having a problem-free battery, as those from these major manufacturers had problems to varying degrees:

Of all the large battery manufacturers, Sony was the only one to emerge from testing smelling of ozone scented roses.

While dealing with a large manufacturer is no guarantee of a hassle-free experience, they are at least likely to still be around to honour their warranties if and when something goes wrong. This wasn’t always the case with small suppliers. One battery — the Aquion — didn’t work on arrival, and its manufacturer went bankrupt before the problem could be rectified. (Although I suppose it’s possible the company went bankrupt because the problem couldn’t be rectified.)

Phase 1 Tests

Of the eight batteries from the earliest round of testing that starting in March 2016, I’ll give quick updates on four produced by large manufacturers. I’ve put them in rough order of how well they performed:

- Sony Fortelion

- Samsung AIO 10.8

- Tesla Powerwall 1

- LG Chem LV

Sony Fortelion: This was the clear winner from the first round of testing. It has been cycled 2,610 times and has still retained 85% of its original capacity. If cycled once per day, that would represent 7.2 years of use. This is the only one of the eight batteries tested in Phase 1 to operate without a problem. Fingers crossed, it continues to operate for many simulated years to come. This is the best evidence I know of that modern home batteries1 can reliably function for over 7 years when done right. Unfortunately, the Sony Foretelion is apparently no longer available in Australia.

Samsung AIO 10.8: The Samsung AIO 10.8 has also been sold under license as the Hansol AIO 10.8. This was due to an image problem resulting from exploding mobile phone batteries. This problem has been fixed. It cost Samsung vast amounts of money, so they have a strong incentive to make sure it doesn’t happen again. That is a strong incentive in addition to the fact they’re not monsters who are okay with people’s phones exploding.

According to the 9th report, the Samsung AIO (All In One) has been cycled 2,730 times. With once a day cycling, that would come to 7.5 years. Unfortunately, this particular unit has become a bit Bolshie. One month before the latest report came out, it sometimes did not respond to attempts to charge or discharge it.

The battery performance warranty was for the first of 10 years or 6,000 cycles, and that it would maintain a minimum of 65% of its original capacity. So at under 3,000 cycles, it’s not yet halfway. But the system’s warranty is only 5 years, which means it would just about be over.2

Tesla Powerwall 1: This was launched with great fanfare in 2015. It was supposed to revolutionize how homes use energy but has somehow managed to slip into obscurity. Even Tesla doesn’t even bother to put a 2 after their current Powerwall. I’d say they were embarrassed about it, but I’m not convinced the Tesla borg mind is capable of processing that emotion.

“If you are suggesting large companies like Tesla are a type of slow-motion artificial intelligence, then I resemble that remark.”

Because the Powerwall 1 could not be tested in the same way as the other batteries, it’s probably not fair to compare its results. I’ll just say it did better than the average battery tested, but it didn’t impress by doing well under difficult circumstances.

LG Chem LV: This was one of LG Chem’s earlier batteries, and it needed to be replaced after reaching 1,183 full cycles with 78% of its original capacity remaining. This is the supposed equivalent of 3.2 years of daily cycling. This is evidence that even large battery manufacturers with good reputations and long term experience have difficulty producing reliable home batteries.

Phase 2 Testing

Ten batteries were tested in Phase 2 testing, and I’ll cover the performance of six:

Again, they’re in rough order of how well they performed.

Plylontech US2000B: This battery is the clear winner from the Phase 2 testing. It has suffered no problems, and its remaining capacity after 1,940 cycles is estimated at 82%. That’s 5.3 years of daily cycling.

Tesla Powerwall 2: This had a fault and, because of the way it’s made, the Test Centre was unable to monitor its output. After it was replaced, the monitoring issue was resolved. It appears to be at 88% of its original capacity after 1,250 cycles. That’s 3.4 years of daily cycling.

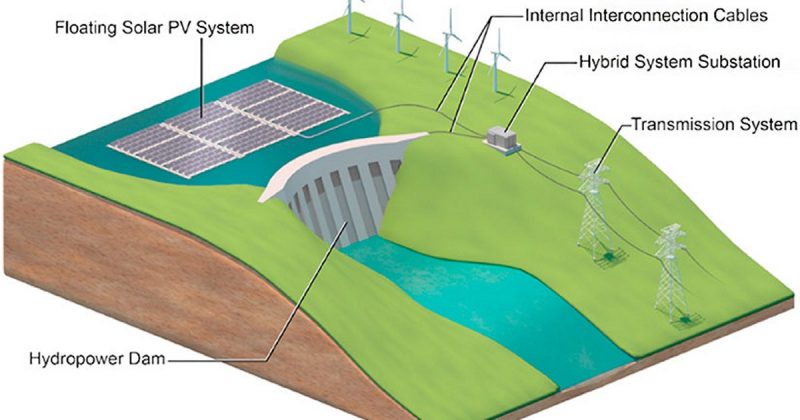

BYD B-Box LV: BYD3 is a giant Chinese battery manufacturer, and for a while, it looked like their B-Box would be the top performer of Phase 2 testing. Here’s a graph from an earlier report showing its capacity deterioration compared to four other Phase 2 batteries:

As you can see from the dotted green line shoved through BYD’s dots, it’s capacity deterioration was less than anything else on the chart. Unfortunately, the B-Box developed problems after this graph was made. It has since bitten the dust and is now either in battery heaven or burning in lithium hell. (Hopefully, we’ll soon have effective battery recycling, which will allow them to reincarnate.) BYD has told the Battery Test Centre they will replace it with a newer model.

Because the batteries only deteriorated around 7% after 1,000 cycles — which is around 3 years of daily cycling — this suggests their batteries can go the distance and stay well within their warranty after 10 years of use if they can fix the battery management issues. BYD may become a major player in the home battery market provided they can solve this problem. While not cheap at the moment, BYD batteries are cheaper than most.

LG Chem RESU HV: Like the LV version from Phase 1 testing, this battery system also had to be replaced. Clearly, even giant, highly experienced battery manufacturers have difficulty improving reliability. After 1,110 cycles, which should be equal to 3 years of daily cycling, it had around 84% of its original capacity. This is not impressive when compared to the Sony Fortelion or the Pylontech.

Alpha ESS M48100: This suffered from overheating and was removed from testing. The Test Centre does not give precise figures for its number of cycles or remaining capacity, but from a chart in their 6th report, it appears to be around 75% after around 1,000 cycles. Alpha ESS say they no longer use this type of battery.

The Redflow Z-Cell: This battery is produced overseas by the Australian company Redflow. It stands out for several reasons, and only one is due to it being the only zinc bromide battery. The Redflow Z-Cell also takes the prizes for…

- The worst run of breakdowns.

- Most dogged determination to keep trying until they got it right.

Their Z-Cell battery unit needed to be replaced four times. The first time due to contaminated electrolyte and the other three because of electrolyte leaks. But rather than give up and just refund the money, as some other battery manufacturers did, Redflow kept replacing systems with improved versions, and now they appear to have finally got it right. When the 9th report came out, it had operated for nearly a year and a half without needing to be replaced. So if you get a Redflow Z-Cell now, it will probably work. If it doesn’t — provided they extend the same courtesy to customers as they do to the Battery Test Centre — it will be replaced.

Because the Z-Cell uses different battery chemistry, it is not supposed to suffer capacity deterioration like lithium, or lead-acid batteries. But in real life, things don’t always work out the way they do in theory, and the ZCell appears to have 97% of its original capacity after 860 cycles or 2.4 years of daily cycling. It remains to see if this deterioration will continue or if it will level off.

Phase 3 Testing

Around March last year, the Canberra Battery Test Centre installed eight new batteries for their Phase 3 testing. When the latest report came out, testing had taken place for under 6 months. This is not enough time to draw any real conclusions about capacity deterioration, as even with accelerated testing, it’s only equivalent to 16 months of daily cycling. Fortunately, no system has stood out so far by having disastrous capacity deterioration.

Unfortunately, one battery system has already failed, while three others are underperforming. It’s pretty bloody tragic that even for batteries installed in 2020 only half work as they’re supposed to.

The system that currently does not work is the…

- BYD B-Box HVM

The three that are underperforming and appear to have similar problems are…

Those that have so far chugged along acceptably with only minor issues are…

Fingers crossed, the overall results from this latest round of testing turn out better than the previous two.

Phase 3 Failures

These batteries did not perform as they should have:

BYD B-Box HVM: This was installed in June, and after being temporarily switched off in July, it refused to switch back on again. With BYD’s help, they were able to help get it going again. But in August, it shut down, and now it can’t be switched on again for more than a few minutes. At the time of the latest report, BYD was trying to work out what the hell was going on with it.

These unfortunate events only reinforce my opinion that BYD’s home batteries would be great if they worked.

Deep Cycle Systems (DCS) PV 10.0: This system was made in Queensland with Chinese batteries. Its rate of continuous charge and discharge is much lower than it should be. At the moment, if it’s discharged by more than around 2.5 kilowatts, it will shut down well before it runs out of available stored energy. Because of this, it is being cycled at a slower rate than is normal for lithium batteries at the Test Centre.

PowerPlus Energy LiFe Premium: This has a similar problem to the Deep Cycle Systems battery above. If power is drawn at a similar rate to other tested batteries, it will shut down before all the available energy is provided.

Zenaji Aeon: Zenaji is an Australian company, and their battery uses lithium titanate cells that I believe are made in China. Despite having the most anime sounding name of all the batteries, this was not enough to protect the Zenaji Aeon from problems, and it also cannot be charged or discharged at its expected rate. It was installed with an SMA inverter, and Zenaji have informed the Test Centre they no longer consider that inverter to be compatible with their battery and offered them a Schneider inverter. The Test Centre said they’ll keep using the SMA until Zenji provides them with a Victron inverter4.

A Lack Of Communication

The three batteries unable to charge or discharge at rates equal to their stated capabilities lack a communication link between the Battery Management System (BMS) and the inverter. This simplifies installation but means the inverter must independently decide for itself how much power the battery can discharge or be charged with. I presume that because people complain more about fried batteries than underperforming ones, the inverters err on the side of caution.

Before getting one of these “dumb” batteries that don’t communicate with inverters, I would make sure the supplier clearly commits to what kind of performance it will provide with the specific inverter used. Then, under Australian Consumer Guarantees, they’ll be required to provide a remedy if you don’t get it.5

Phase 3 & Functional

These four systems work as they are supposed to, so far:

FIMER REACT 2: This baby is stuffed full of Samsung battery cells. Enough to give it 8 kilowatt-hours of nominal storage, although 4 and 12 kilowatt-hours were also options. It has worked without a problem so far.

FZSoNick: This particular battery is special and not just because it sounds like a creature from The Dark Crystal.

This is FZSoNick’s cousin, Fizzgigg.

This battery, neither lithium, nor lead, nor zinc bromide be.

It is a sodium nickel chloride battery and operates at 265 degrees. The need to warm up can cause a delay before they can charge or discharge. Fortunately, it’s well insulated and only feels warm to the touch. So bad luck if you want it to double as a barbeque hot plate. They’re made in Switzerland, so perhaps the Swiss like snuggling up to them at night when they’re not poking holes in cheese.

I don’t expect this battery type to take over from lithium but, as far as I’m concerned, the more battery types, the merrier. If it works reliably, it may have an edge.

SolaX Triple Power: Solax is a Chinese solar inverter manufacturer, and the cells in their battery system are made by the Chinese company Shenzhen BAK Power.

To build this giant city, the people of Shenzhen really had to put their BAKs into it. (Image: Financial Times)

So far, it has operated without a problem.

SonnenBatterie: While there were some difficulties with installation, this German-made battery has operated without problems.

A Shift Towards Integrated Battery Systems

The Canberra Battery Test Centre says their acquisition of battery systems for Phase 3 testing indicated there was increasing integration in the battery market. More are being sold that combine the battery and inverter into one system or consist of battery packs that are only compatible with inverters from the same manufacturer. There are also increasing requirements for online registration of batteries as well as internet monitoring of their use.

It is a little odd that they are pointing this out when three of their new batteries are dumb types that don’t directly communicate with their inverters. But since all three of them don’t operate as they’re supposed to, they have first-hand experience of why integration appears important. Suppliers increasingly want tight control over exactly how batteries are charged and discharged. This appears vital for optimal performance and reliability.

This trend towards greater integration matches up with what I’m seeing. There has not been a trend towards lithium batteries becoming tough enough to handle varying charge and discharge characteristics from a range of inverters. Instead, the focus has been on providing delicate batteries with the exact conditions they require to last long term.

Battery System Prices Falling?

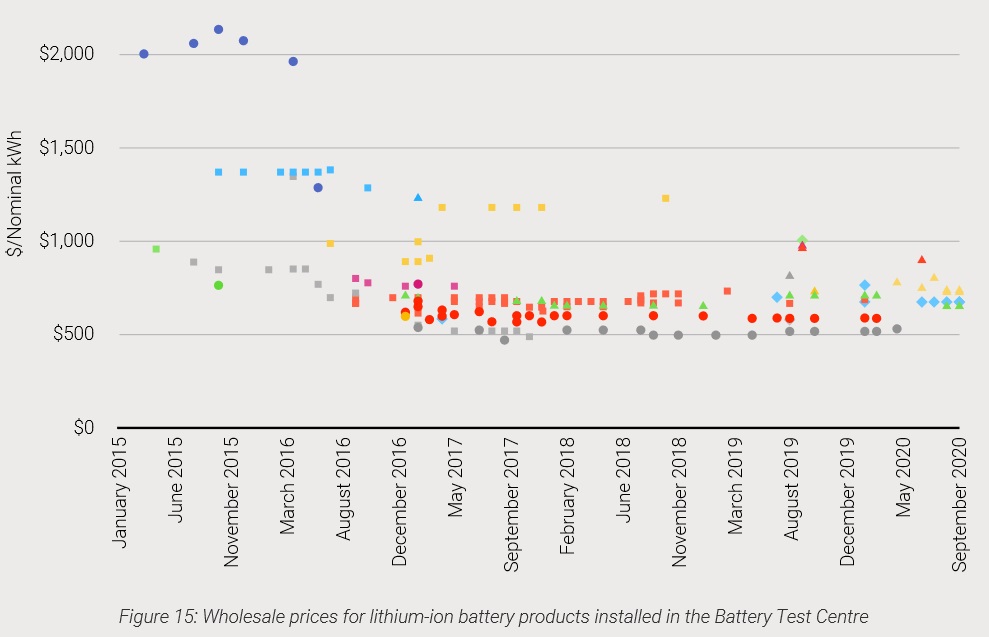

The Test Centre says battery prices have fallen since they started testing, but this doesn’t give the full picture. While prices did fall four or five years ago, as far as batteries are concerned, that’s the distant past, and they haven’t really fallen in price for the past two years. Falling costs of lithium battery cells have so far not translated into lower costs for home battery systems.6

The prime example of this is the Tesla Powerwall 2, which has increased in price by around 43% since it was launched in 2017, after taking inflation into account.

South Australia’s high battery subsidy that used to be available probably played a role in keeping prices high, but the main reason prices haven’t fallen appears simply to be that building reliable home battery systems is obviously very difficult. Every battery system that is sold has to be expensive enough to cover a high failure rate. If some company offers you a home battery at a rate far less than what large companies charge, they probably aren’t putting aside enough to pay for inevitable replacements, and if and when your battery develops a problem, they’re likely to have disappeared.

The good news is, even though it’s taking an excessively long time, reliability is improving, so there is a lot of room for large falls in home battery prices once manufacturers are confident only a few percent of their systems will develop major problems.

As this graph from the 9h report shows, there have been no large falls in battery prices for years.

My Brilliant Conclusion

My brilliant conclusion isn’t that brilliant and is actually three separate conclusions. But maybe if you squish them together and look at them from the right angle at a distance, they’ll look kind of brilliant.

- Don’t buy a home battery yet if your goal is to save money. They will fall in price, and once they do you can buy one and be confident your wallet will come out ahead.

- If you do get a home battery, make sure you are absolutely clear on what it will do after installation in your circumstances and get it in writing. This will make it easier to force the supplier to fix the problem if it underperforms.

- Given the massive failure rate for home batteries, don’t buy one from a small supplier/manufacturer in case they go bankrupt and leave you without warranty support. Not unless you like gambling. Or, to be more precise — not unless you enjoy losing at gambling.7

When the next Canberra Battery Test Centre Report comes out, which may not be long, there should be enough data to realistically compare the rates of deterioration for the new Phase 3 batteries. I am pretty confident most of them will still be working by then.

Footnotes

- Not ye olde lead-acid or nickel-iron batteries. ↩

- I’m not a lawyer, but under Australian consumer law, it appears if you give the batteries of a system a 10-year warranty, you may have given the entire system a 10-year warranty, because a normal person would probably think a 10-year performance warranty means the entire battery system is warranted for 10 years. ↩

- Supposedly BYD stands for “Build Your Dreams”. Personally, I think they just made that up when someone asked them what the letters were supposed to stand for. ↩

- Victrons are great inverters. Except for the fact they’re made by the Dutch. ↩

- It’s not necessary to have a clear commitment in writing for Australian Consumer Guarantees to apply. Verbal promises are enough. But it can be beneficial for everyone’s blood pressure if there’s documentation. ↩

- Raw materials such as lithium and cobalt make up a small portion of the cost of a $1,000 per kilowatt-hour battery system, so fluctuations in their prices currently aren’t very important for home batteries. ↩

- Is this advice unfair to small manufacturers with a good product that are doing everything right? Hell, yes. ↩

Original Source: https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/battery-test-centre-reports/