Torture Testing Reveals Modern Solar Panels Are Tougher Than Ever

PVEL 2022 PV Module Reliability Scorecard — More Panels Pass All 5 Main Tests Than Ever Before.

PVEL stands for PV Evolution Labs. Their speciality is torturing solar panels to determine how tough they are. Every year they publish a report that separates Top Performing panels from those they don’t call Top Performing. This year was no different — except in the ways it wasn’t the same.

This time, instead of their usual long report, they only put out a 10-page summary. I don’t know why they’d do this. Putting effort into writing a lengthy report and then people making fun of it on the internet is the peak human experience.

Despite its brevity, there’s very useful information in the ten pages called:

“2022 PV Module Reliability Scorecard: PDF Summary”

You can download the document here.

In this article, which will be a summary of a summary, I’ll briefly describe…

- PVEL testing methodology and what we can conclude from the results they provide.

- How PVEL is obsessed with nice BOMs.

- The five main physical tests they inflict on solar panels.

- Which panels passed all five tests and became Champions of ToughnessTM1.

It’s a pity they shrunk their format this year because they didn’t even have room to emphasise that far more panels passed all five physical tests than ever before. Because PVEL doesn’t test a random sample, we can’t be sure the durability of panels has improved, but I’m going to say they have anyway.

“Yep… I’m pretty sure this is a solar panel.”

PVEL Methodology

Manufacturers pay PVEL to see how well their panels stand up to abuse. PVEL follows a strict methodology involving factory witnesses who ensure modules are made with the correct materials and choose solar panels for testing by randomly selecting them off the assembly line to ensure everything is above board.

After subjecting panels to grueling tests that simulate decades of exposure to the elements, those that suffer minimal deterioration — generally under 2% — are called “Top Performers”. Each year PVEL publishes which panels received Top Performer status, as they did in their summary this year.

They don’t publish which solar panels failed or whether or not they tested a particular panel. This means we can use the information they provide to say a panel is good, but we can’t say a module that isn’t a Top Performer isn’t good because we have no way of knowing if it was tested.

If I had a lot of money2, I could buy a full version of the report with information on which panels failed, but they’d only sell it to me if I promised not to write about it.

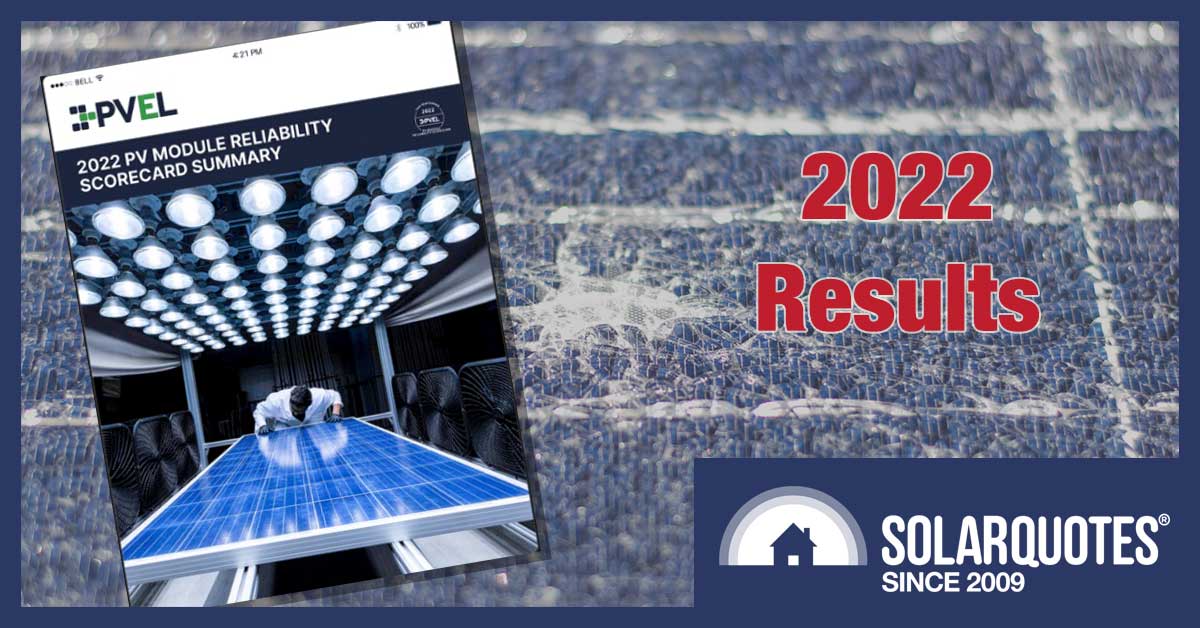

Usually I’d find exciting bits of solar information in their scorecard report, but this year I’ve had to scrape them off the PVEL website instead. This graph shows a temporary solar glass shortage starting in late 2020 due to many manufacturers switching to thinner, 2mm sheets. (Image originally from Exawatt.)

Bill Of Materials

The list of components used to make a solar panel is called a Bill Of Materials or BOM. Panels that are the same model can use different Bills Of Materials. This can affect module durability and how likely they are to pass tests.

If you want to build a solar farm, you can pay PVEL for the detailed version of their report that provides information on which BOMs are the most durable. You can then go to a manufacturer and demand they get off their lousy BOMs and make panels for you with a BOM that can be exposed for decades to the Australian outdoors without problem.

If you are a homeowner putting solar panels on your roof, you don’t have the market power to demand a specific BOM. What does improve your chances of having a nice BOM is Australia’s consumer law. Australian Consumer Guarantees mean you can receive a repair, replacement, or refund for a defective product regardless of its warranty or the small print it may contain. This applies to any panel manufacturer with an office in Australia. If they don’t have an office, then it applies to the importer. So if you buy a panel from a manufacturer with an office in Australia that intends to do business here long term and has a reputation to protect, then chances are your BOM will be fine.

PVEL’s 5 Physical Tests

PVEL has five main physical tests they put solar panels through to determine how likely they are to resist different forms of panel degradation over decades of exposure to the elements:

- Thermal Cycling

- Damp Heat

- Mechanical Stress Sequence

- Potential Induced Degradation (PiD)

- Light-Induced Degradation (LID) + Light and Elevated Temperature-Induced Degradation (LeTiD)

The PVEL summary also gave information on PAN Performance; which is a simulation of how well panels will perform in a solar farm, but the results aren’t very useful for rooftop solar power, so I won’t go into it.

I describe the five main tests below:

1. Thermal Cycling

Solar panels heat up during the day and cool down at night. This temperature change is called a thermal cycle.

And then god sent a rainbow as a message to the world that, once more, she had thermally cycled the solar panels.

Temperature change causes different materials to expand and contract at different rates. This puts the joins between them under strain. Over time this can damage the electrical connections in solar panels and decrease performance. Passing this test is especially important for panels in the outback, where the temperature difference between day and night is often extreme.

The test involves cooling panels to -40°C and then raising them to 85°C. This is done 600 times. The 125°C temperature differential is much greater than a module would normally ever experience in use. I’d have a tough time surviving even one cycle, but PVEL says 90% of tested solar panels tested degraded less than 2% and were classed as Top Performers. This indicates manufacturers have come a long way on this measure of reliability.

2. Damp-Heat

High temperatures and humidity are bad for electronics, and solar panels are electronic. Exposure to conditions found in tropical Australia can cause:

- Moisture ingress: Water getting into anything with electricity running through it is bad.

- Delamination: Solar panels are held together by epoxy3 and in severe cases, this can degrade and cause the panel to start peeling apart.

- Corrosion: While there’s normally no steel to rust in solar panels, other metals can corrode, and heat and humidity contribute to it.

PVEL locks the panels in a test chamber at 85°C and 85% humidity for 1,000 hours to test how well the modules resist these problems. Then, when they think it’s over, to crush their spirits completely, they do it all again for another 1,000 hours.

PVEL said 50% of panels tested degraded less than 2% after this sauna torture. But one module in this round of testing was the worst they’d ever seen, with a 54% fall in performance. You’d want to avoid installing one like that in Darwin.

Some panels recovered some of their lost performance after resting at normal temperatures and humidity. Since the test conditions were unrealistically bad, involving conditions not seen in real life, it seems fair to count their performance after they’ve had a break. A total of 27% of the solar panels tested that suffered less than 2% deterioration only achieved this after the rest period.

3. Mechanical Stress Sequence

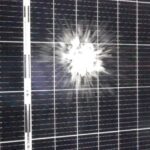

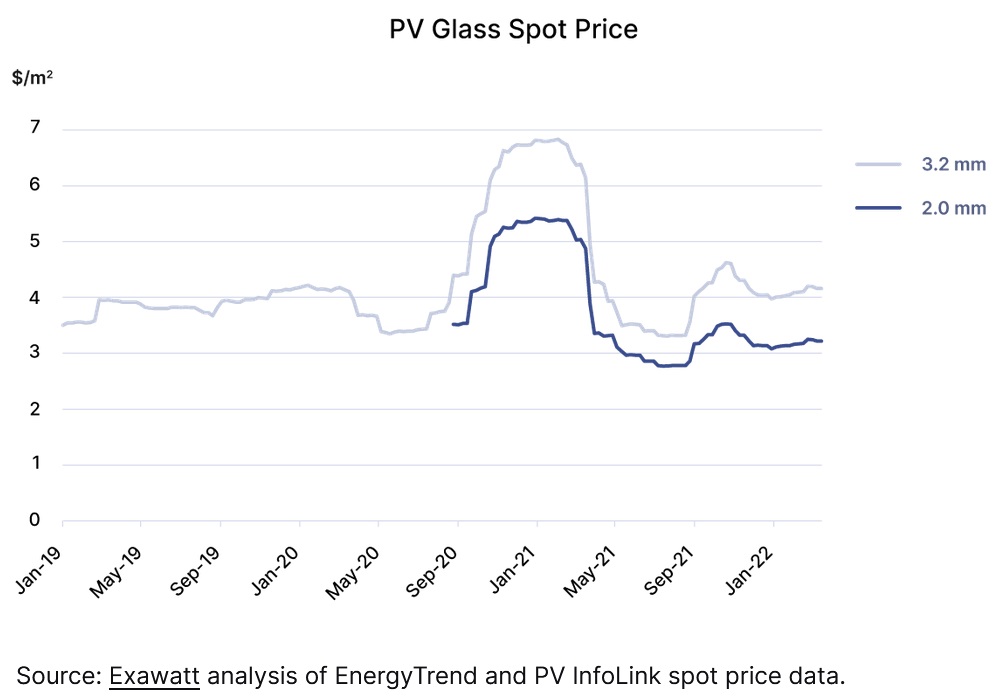

Panels can flex in the wind, and this places them under mechanical stress. Snow piling up can do the same. This stress can reduce output by causing solar cells to crack and damaging electrical connections. This can create dangerous hot spots rapidly leading to panel failure.

In a worst-case situation, the panel glass can break. This usually doesn’t happen outside of cyclones, but PVEL testing is severe, and the majority of solar panel failures were due to broken glass rather than loss of output.

Here’s a panel where the glass broke under mechanical stress applied by PVEL’s robotic stomp-a-tron. (Note: “Robotic stomp-a-tron” is a completely made-up term. But it should be real!) Image credit: PVEL

Of the panels tested, 72% had glass that resisted the punishment without breaking while also suffering less than 2% deterioration in output. Longer panels were more resistant, with 80% of those that passed being over 2.1m long while only 68% of modules shorter than this passed.

4. Potential Induced Degradation (PID)

Potential Induced Degradation, or PID for short, is a type of degradation more likely to occur in hot and humid climates. Its technical cause is positively charged sodium ions moving from a panel’s glass cover to its solar cells because they’re attracted to stray electrical currents. The result may look like snail trails on solar cells and can reduce a panel’s output by up to 30%.

The test for PID involves putting the modules in sauna-like conditions, as in the Damp Heat Test, while passing the panel’s maximum rated voltage through them for 96 hours.

Fortunately, solar panels from reputable manufacturers no longer suffer from a significant amount of PID. But there are some for which it is still a severe problem. Of the panels PVEL tested, 5% suffered more than 8% deterioration in output.

5. LID + LeTiD

Light-Induced Degradation (LID) is a normal and usually minimal form of degradation in all P-type solar panels. Beyond an expected small amount, it’s usually not a problem.

Light and Elevated Temperature-Induced Degradation (LeTID) is a type of degradation that normally only occurs in significant amounts in PERC panels.

The test for both these problems involves subjecting solar panels to light as intense as full sunshine for 486 straight hours. That’s nearly three weeks.

Results show manufacturers appear to have both these problems well under control, as only one of the panels tested suffered degradation over 3%. PVEL attributed this to improvements in cell doping. This is where tiny quantities of the desired element are added to solar cells under controlled conditions.

Don’t try this at home, kids. The solar panel will never supply enough power to keep the lights going. Image credit: PVEL

Limits To Knowledge

PVEL only says which panels passed their tests and became what they call Top Performers. They don’t tell us which panels failed or if a module was tested at all. This means we can’t say a panel that didn’t get Top Performer status is bad. All we can conclude is that panels that did get Top Performer status are probably good. While it would be nice to have all the information, just knowing which ones we can be confident are good is still useful.

Champion Solar Panels

This year 15 manufacturers had one or more solar panels that passed all five physical tests. In the past, only a few panels at best would pass all the main tests, but this year 30 panels passed all five tests. If we don’t count otherwise identical panels that only differ in size, the number drops down to 17, but this is still a far better result than any other year.

I hereby declare the panels that were Top Performers in all five tests to be Champions of Toughness! I can’t guarantee the solar panels listed below will operate without problem for decades, but I’m confident the odds are good. While a panel may be made with a low-quality Bill Of Materials (BOM), which will reduce its reliability, this is not likely to occur if they are from a manufacturer with an Australian office that has made a credible commitment to selling here long-term. This is because they won’t want the expense of replacing panels that fail.

The same applies to any Australian company that imports panels from manufacturers that don’t have an office here. If the importer is a trustworthy and reliable company and intends to be in business for many years to come, then they are likely to ensure the panels they import are reliable.

Two things to note about the Champions are:

- Many are large panels made for solar farms and over 2.1m in length. These can be installed on residential roofs but sometimes don’t fit.

- Many — such as the Boviet, ET, and Trina panels — are bifacial and have glass on both sides. Because they can use light from behind, this makes them more suitable for ground mounts or tilt racks rather than installed centimetres above a roof, as most residential solar is.

I’ve listed all 30 solar panels that are Champions of Toughness below. I included links to the panel’s datasheets if the manufacturer has them on their website and made them reasonably easy to find:

The number of panels that are Champions of Toughness are around an order of magnitude6 higher than previous years. This makes me confident that solar panels from good manufacturers have significantly increased in quality over the past few years. Not only have solar panels fallen dramatically in price over the past decade, they have also had large increases in reliability.

Footnotes

- In these circumstances, the letters TM stand for “Toughness Mark” and have no other legal bearing whatsoever. ↩

- I’m so rich my Hyundai Getz has half a tank of petrol. I just thought I’d mention this in case there are any ladies out there who are impressed by ostentatious displays of wealth. ↩

- Epoxy is a word that means the same as glue, except you sound smart when you use it. ↩

- When you see “xxx” in a panel’s designation, it stands for its wattage, which can vary. But India is really convinced “xxx” means something is dirty, so Adani and other Indian manufacturers such as Vikram use “AAA” instead. ↩

- The PVEL summary uses a “D” in these panels’ designations, but I believe it’s a typo and it should be “P”. ↩

- “Order of magnitude” is a phrase that means the same as “10 times higher”, except you sound smart when you use it. ↩

Original Source: https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/pvel-2022-panel-scorecard/